The mayor of Albany, New York, has ordered a statue of Revolutionary War General Philip Schuyler removed from the front of city hall, where it has been on view since 1925. Before it’s gone, we should consider why Schuyler still deserves to be honored.

Read our president general’s appeal to Mayor Sheehan to reconsider her order here.

The success of the American Revolution was made possible by an unlikely alliance of Americans, including farmers, tradesmen, urban working people, men and women pushing the frontiers of American settlement into the valleys beyond the Appalachians, free blacks for whom Revolutionary ideals of liberty were deeply and personally meaningful, and Virginia planters for whom the war risked family fortunes built over generations. Few moments in our history have brought together such a wide range of people in a single cause.

All modern Americans benefit from their sacrifices, but in enjoying the freedom they won, we have grown forgetful and ungrateful about what they have done for us. At this time in our history, many of our countrymen find it difficult or impossible to acknowledge our debt to people from our shared past who did not share all our values. The revolutionaries were not like us. They were born into a world in which freedom as we understand it was barely an aspiration. They fought to create a republic—a government organized to promote the interests of ordinary people—and began the task of pushing back the darkness of centuries. We are all their heirs and successors. We owe them honor and respect.

Philip Schuyler of New York is now among the least appreciated and, sadly, the most dishonored. He was among the most interesting and the most unexpected of our revolutionaries. He was a privileged member of one of the most prominent landed families in the Hudson River Valley. The Schuylers were major Hudson Valley landowners before New York was New York. A family of Dutch patroons, the Schuylers and their network of relatives, allies and clients dominated the Hudson Valley as completely as any group of landowning patricians in colonial North America.

British America had no native aristocracy—no class of hereditary landed aristocrats who lived on rents and enjoyed the drawing room leisure so ably portrayed in the novels of Jane Austen—but the Schuylers and their peers along the Hudson came as close to it as anyone in Britain’s American colonies. The southern planters may have longed for the leisure of British aristocrats, but they were, in fact, market farmers whose fortunes rose and fell with prices of the crops produced on their plantations. Hudson Valley patroons like the Schuylers owned vast estates and had tenants—uncommon in the colonies where land seemed inexhaustible and most colonists aspired to own their own farms.

We used to say that the American Revolution was the inevitable result of the social and economic development of the colonies, which, the argument went, was making them continuously more egalitarian, more democratic and less British. But in important ways, the colonies were becoming more like Britain in the last generation before the American Revolution. The first stubborn pockets of urban poverty were appearing, as was a middling sort that was defining itself through consumption—drinking tea, wearing imported fabrics, imitating European fashions and reading the latest British books. And an aristocracy, comparable in style and influence to its much more powerful British model, was starting to form. In important ways, America was becoming more British, not less, on the eve of the Revolution. This was the thesis of the late John Murrin, one of his generation’s most creative historians, who died a few weeks ago from COVID-19.

Philip Schuyler embodied the colony’s increasingly British character. Born in 1733, he was the heir to fortune and privilege. He expected to exercise privilege and pass it on. That he became a revolutionary is extraordinary. He had everything to lose from the Revolution, and the possibility of gain was hardly sufficient to justify the risk he took. If money and social standing alone had defined him, he would have stood beside the DeLanceys and the other loyalist families of New York.

As the eldest son, Philip Schuyler inherited the landed estate of his late father in 1754, and divided it with his siblings. His own holdings, stretching along the Hudson and the Mohawk, were princely. Among them his estate at Saratoga was the most valuable. He owned and built mills at the falls of creeks and acquired a schooner and sloops to trade on the Hudson. But it was the development of his own estates by encouraging emigration from Europe that occupied much of his attention. In the last years before the Revolution, Schuyler was looking forward to making his estates something like the estates of Britain’s landed aristocracy, peopled by tenants paying rents to support a way of life to which few Americans could aspire.

Like George Washington, Schuyler was a veteran of the French and Indian War, an innovator and an energetic entrepreneur. Both men were interested in canals and other improvements to facilitate commerce. Washington saw that tobacco had little future and in 1769 he abandoned tobacco and planted wheat, setting off on decades of creative farming. Schuyler decided to grow flax, and in 1767 built a flax mill to make linen, the first of its kind in America.

In that same year Schuyler was elected to the New York Assembly. He was no radical, but a firm supporter of colonial rights, both in the growing dispute with Britain and at home. In the spring of 1769 he proposed a bill to provide for religious toleration, “to encourage the worship of God,” he wrote, “upon generous principles of equal indulgence to loyal Protestants of every persuasions,” and—ever practical—to make it possible for all Protestant denominations to own real estate for the support of their churches. But practical as he was, he was a man of principle. When patriots denounced a scheme to provide funding to support the king’s troops in the colony, Schuyler was the only member of the assembly who took their side.

News of the fighting at Lexington, characterized as a massacre, reached Schuyler on April 29, 1775. That evening he shared his reaction in a letter to a friend. “I know there are difficulties in the way,” Schuyler wrote. “The loyal and the timid in this province are many, yet I believe that when the question is fairly put, as it is really put by this massacre in Massachusetts Bay, whether we shall be ruled by a military despotism, or fight for right and freedom? the great majority of the people will choose the latter.” Unless Britain chose a course of wisdom and conciliation, he predicted, war was inevitable. “It is now actually begun,” he added grimly, “and in the spirit of Joshua I say, I care not what others may do, ‘as for me and my house,’ we will serve our country.”

He might have remained comfortably at home on his Hudson River estates, but principle led him away. On May 9, 1775, Schuyler set off for Philadelphia as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Within six weeks he had been named a major general in the Continental Army. Schuyler rode north with George Washington as far as New York City, then turned north toward Albany to take command of the army’s Northern Department (known at first as the New York Department)—a largely autonomous post in which he was responsible for defending the colonies from an attack down the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor connecting the seaboard colonies with Canada.

The corridor had been fought over by Britain and France in a succession of wars that consumed much of the eighteenth century and was dotted with forts. The most important, Fort Ticonderoga, dominated the southern end of Lake Champlain and controlled the portage between Lake Champlain and Lake George. The latter stretched thirty-two miles south and connects to a narrow portage to the Hudson River about fifty miles north of Albany. The rivers and lakes in the corridor provided a nearly continuous water route from the Hudson to the St. Lawrence, and was the natural route for the colonists to use to conquer Canada or for the British to follow to take control of the Hudson Valley and cut New England off from the colonies to the south and west.

Establishing military control of this region was a desperate challenge. To the west of Albany, in the Mohawk River Valley and northward to the Great Lakes was the land of the Iroquois, a confederacy of powerful, warlike Indian tribes more likely to fight with the British than the Americans because they knew that the British, at least for the moment, valued their trade more than their land, which the Americans coveted. To the east, in the mountain valleys between New York and New Hampshire was a region—what would become Vermont—claimed by both colonies and peopled by New Englanders who seemed as likely to take up arms against New Yorkers as to fight the British. To the south, along the Hudson all the way to Manhattan, New Yorkers were divided between patriots and loyalists. The British on the St. Lawrence River were, in the summer of 1775, among the least of Philip Schuyler’s worries.

To take control of this critical, complex and confusing region, Schuyler had only a fragment of the armed strength of the colonies. Most of the available manpower was dedicated to Washington’s army confronting the British outside Boston. Schuyler had Continental troops raised in New York and other units, mostly militia, from New York and adjacent parts of Connecticut and western Massachusetts. They were barely sufficient to man the outposts spread across a wide arc from the hazy borderlands of Vermont to the Mohawk River Valley. Adding to his difficulties was the distrust many New Englanders felt for New Yorkers, and their resistance to being placed under the command of New York officers, including Schuyler himself. Arms and gunpowder were in desperately short supply, and providing his men with food, clothing and other necessities was a continuous challenge. To make matters worse, a drought made it impossible to feed what livestock he could gather.

At Ticonderoga, Schuyler found the troops there undisciplined and inattentive, but he thought he could get them into shape. “The officers and men are all good looking people,” he wrote to Washington “and decent in their deportment, and I really believe will make good soldiers as soon as I can get the better of this non-chalance of theirs. Bravery I believe they are far from wanting.” Washington responded in kind about the troops at Cambridge, but assured his new friend that “patience and perseverance” would turn their men into soldiers.

In late September Schuyler wrote to Washington from Fort Ticonderoga, admitting “the Vexation of Spirit under which I labour.” His health (“a Barbarous Complication of Disorders,” he called it) had not been good for years, and only grew worse under the pressures of his assignment. He was constantly anxious that “the Army should starve” despite his constant efforts and frustrated by the “scandalous Want of Subordination and Inattention to my Orders” by the officers scattered through his widely dispersed command. “If Job had been a General in my Situation,” Schuyler concluded, “his Memory had not been so famous for Patience—But the Glorious End we have in View & which I have a Confidential Hope will be attained will attone for all.”

By the end of November Schuyler had had enough, and considered resigning. “Our Army requires to be put on quite a different Footing,” he wrote to Washington. “Gentlemen in Command, find It very disagreeable to Coax, wheedle and even to Lye, to carry on the Service. Habituated to Order, I cannot without the most extreme Pain, see that Disregard of Discipline, Confusion & Inattention which reigns so General in this Quarter.”

Despite his frustrations, Schuyler remained at his post. His health made it impossible for him to accompany American troops on the Canadian expedition, but he funneled men and supplies north. When the campaign failed, he organized a strategic retreat down the Lake Champlain corridor that helped prevent an effective British counteroffensive from reaching the Hudson in the fall of 1776, which would have been disastrous for the American cause.

The next year Schuyler met British General John Burgoyne’s offensive south from Canada with skillfully executed delaying tactics. British maneuvers forced Schuyler’s army to evacuate Fort Ticonderoga—an enormous blow to American morale—but Schuyler delayed Burgoyne’s overland march to the Hudson by having his men fell trees in the narrow road, slowing the British pace while he gathered troops for a showdown with Burgoyne on ground of his own choosing.

George Washington—among the most perceptive spectators to the Saratoga campaign—believed that “Burgoyne’s army will meet, sooner or later an effectual check” and that his success in penetrating so far south “will precipitate his ruin.” Washington believed that by detaching troops to gather supplies, Burgoyne was pursuing a “line of conduct . . . most favorable to us,” offering the opportunity to defeat him in detail. In late July 1777 Schuyler suggested to Washington that if he brought the main army north to Albany, together they might cut Burgoyne’s overextended army to pieces.

Washington could not risk the maneuver. Schuyler was left to operate with his small army. At the beginning of August he stationed his troops near Stillwater, beside the Hudson a few miles south of his own Saratoga estate. Burgoyne’s troops destroyed Schuyler’s house and mills as they passed. Schuyler’s army was plagued by desertion and illness, but he explained to Washington that “if we by any Means could be put in a Situation of attacking the Enemy and giving them a Repulse, their Retreat would be so extremely difficult that in all probability, they would lose the greater part of their Army.”

Schuyler was not to command that attack. Congress, frightened by the evacuation of Ticonderoga and worried that Schuyler would lose Albany without a fight, relieved him and turned the Northern Army over to Horatio Gates, who had spent weeks in Philadelphia criticizing Schuyler and angling for the command. “We shall never hold a post until we shoot a general,” John Adams wrote to Gates. Losing his command was humiliating to Schuyler, but he remained to offer whatever assistance he could as the armies prepared for battle on his own home ground.

We will never know whether the sprawling, month-long series of battles and maneuvers remembered as the Battle of Saratoga would have resulted in the same dramatic victory if Philip Schuyler had been left in command. Certainly Gates did not distinguish himself as a commander at Saratoga. The battles that sealed the American victory were directed by subordinates who would have acted with as much courage and energy for Schuyler as they did under Gates, who did not know the ground as well as Schuyler and who remained far behind the lines while the victory was won.

Although Schuyler stayed with the army, Gates studiously avoided him. Burgoyne’s surrender made Gates a hero. Congress voted to present him with a gold medal to commemorate his victory, and Gates spent months maneuvering to replace Washington as commander-in-chief. That effort failed, and his subsequent defeat at Camden, South Carolina, and his headlong flight from that battlefield revealed Gates’ true character as a field commander.

Schuyler expressed no bitterness about the opportunity that had been denied him. Although deprived of his army, Schuyler continued to serve selflessly for the rest of the war—first as Continental Indian commissioner, and later as a member of Congress, promoting effective relations between Congress and the army. He never lost Washington’s respect and esteem.

An original member of the New York State Society of the Cincinnati, United States senator and leading citizen of New York, Philip Schuyler was honored in the early years of the republic. Reviewing the war decades later, Daniel Webster concluded that Schuyler was “second only to Washington in the services he rendered to the country in the war of the Revolution” under “difficulties which would have paralyzed the efforts of most men.” Webster overlooked Nathanael Greene, Henry Knox and Baron Steuben, but his assessment was not too far off.

“He was one of those men,” an early biographer wrote, “who often work noiselessly but efficiently; whose labors form the bases of great performances.” A builder, not given to heroics, Schuyler was “indifferent to that popular applause which follows the enunciation of startling opinions, or performance of brilliant services.” For sustained devotion to the American cause and perseverance in the face of extraordinary obstacles, few officers of the war were his equal. We became, and remain, an independent people thanks to that kind of devotion, and owe Schuyler the honor he richly deserves.

Philip Schuyler came as close as any American of his time to living like a British aristocrat, but fought and helped to win a revolution that ended the possibility of an American aristocracy. We dishonor Schuyler and other heroes of the Revolution when we hold them to modern standards, forgetting that what they created—the first great republic of modern times, based on principles of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and citizenship—is what makes it possible for us to hold those standards, and is the foundation of our own ideas of freedom.

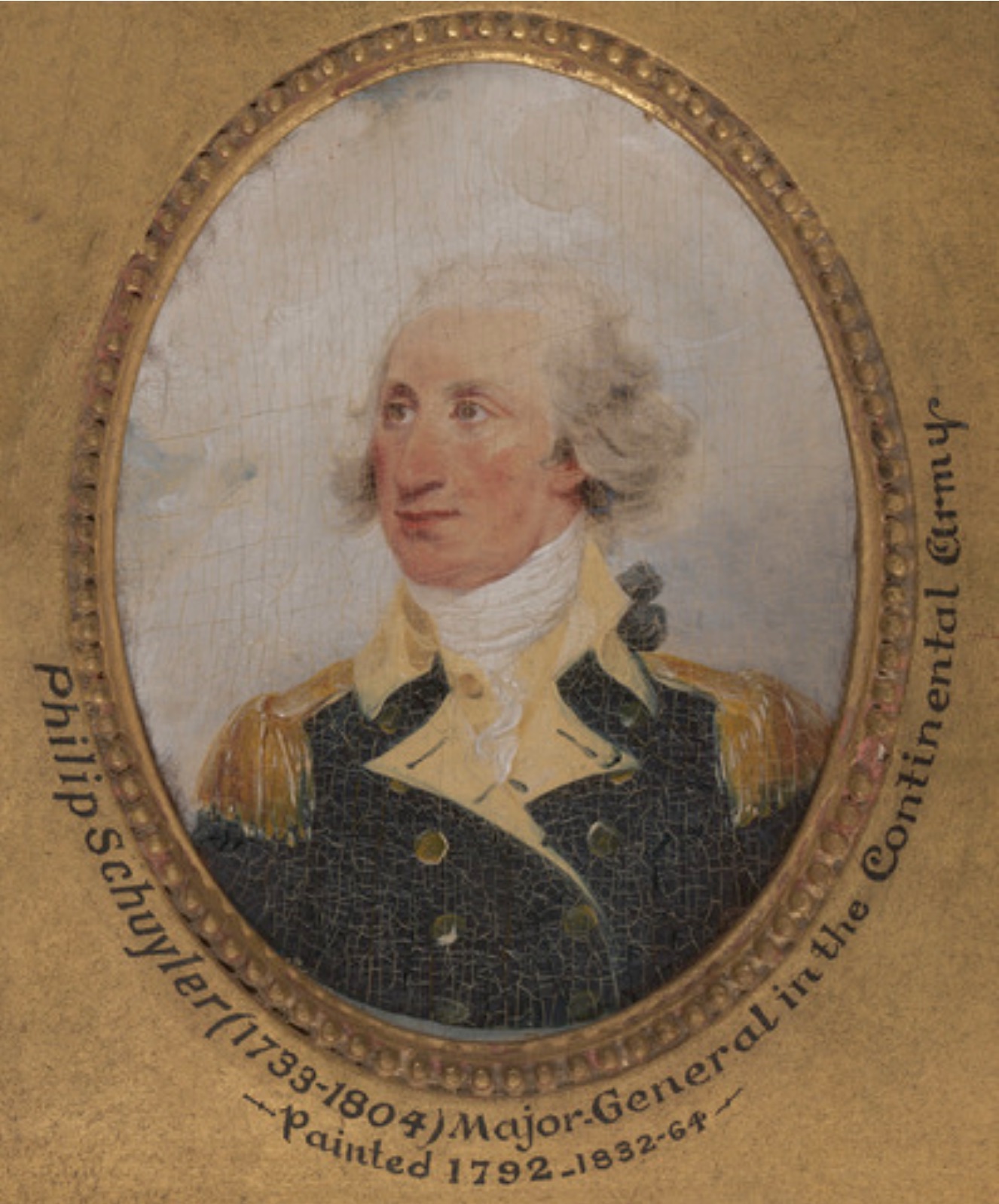

Above: Philip Schuyler by John Trumbull, 1792, Yale University Art Gallery.