What’s Wrong with “The Idea of America”?

By Jack D. Warren, Jr.

June 16, 2020

Rarely has an essay on American history attracted as much attention or aroused as much controversy as “The Idea of America” by Nikole Hannah-Jones, published last August in The New York Times Magazine. The essay is the introduction to “the 1619 Project,” conceived by Hannah-Jones to mark the four hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Britain’s North American colonies.

The initial idea—to use The New York Times Magazine to draw public attention to the four centuries of enslavement, violence, exploitation, oppression and discrimination endured and resisted by African Americans—was a good one. A great deal of important work on slavery, racism and racial conflict in American history and culture has been done over the last fifty years, and while it has shaped the discourse of historians, flowed into high school and college textbooks, and influenced what gets taught in our history classrooms, the kind of broad awareness this work deserves has not been achieved.

Unfortunately this wasn’t what Nikole Hannah-Jones imagined or what the 1619 Project turned out to be. She is not an historian and does not seem to be familiar with the rich historical literature on slavery, racism and racial conflict published over the last fifty years. If she is acquainted with that literature, she chose to ignore it and advances a thesis of her own, asserting that slavery and racism are the central themes of American history and culture, and that they have not just shaped—they define—every aspect of American life, from childhood obesity and health care policy to highway traffic patterns.

The project consists of a series of essays and other materials collectively advancing this thesis. While any effort to attribute every aspect of a nation’s history and culture to a single source is intrinsically flawed, some of the contributions to the 1619 Project are commendable. The essay on sugar and slavery by Khalil Muhammed of Harvard University is well researched and thought provoking. The picture essay by Mary Elliott, curator of American slavery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture—available online but not published in the print edition of the magazine—is also quite good. The same cannot be said for Hannah-Jones’ lead essay, which is cluttered with inconsistencies, incomplete thoughts, incoherent references, unsupported assertions and factual errors.

It might seem uncharitable to point out that the Continental Congress voted for independence on July 2, 1776 (not July 4, as Hannah-Jones wrote, an error the Times has since corrected), or that alabaster is carved, not cast, and is not suitable for monumental statues (she refers to the founding fathers as “those men cast in alabaster in the nation’s capital”), or to point out other factual errors, large and small, that litter the essay, but the accumulation of such errors discredits the work, along with the senior editors who not only published it, but have defended its preposterous claims against the carefully reasoned, thoroughly documented and respectful criticism of some of the nation’s most distinguished historians.

Nikole Hannah-Jones is a journalist, not a historian, and she does not pretend to be objective. Her father, she begins, was born in 1945 into a family of sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta, where blacks endured crushing discrimination and violent subjugation. Hoping for a better life, his mother packed her children up and moved to Waterloo, Iowa, but the hoped-for Promised Land turned out to be a segregated city where she cleaned white people’s houses. Hannah-Jones’ father joined the army to escape poverty, hoping “his country might finally treat him like an American,” but the military led only to a series of dead-end service jobs.

Hannah-Jones offers a general interpretation of American history, placing her family’s story, and by extension millions of others, in the context of a four-hundred-year history of racial exploitation and violence that began the moment the first slaves reached Jamestown. “The Idea of America,” and the entire project it introduces, seeks “to reframe American history” with 1619 “as our nation’s birth year.” The result is a vision of America conceived, not in liberty, but in oppression.

To sustain this interpretation, she recasts the American Revolution as a sinister movement and the revolutionaries as monsters whose primary aim was to perpetuate slavery. “It is finally time to tell our story truthfully,” she announces with breathtaking arrogance, while advancing an argument for which there is not a shred of evidence and simultaneously ignoring more than sixty years of extraordinary historical scholarship on slavery and on the nature and achievements of the American Revolution.

Her interpretation rests on the claim that by 1776 Britain “had grown deeply conflicted over its role in the barbaric institution that had reshaped the Western Hemisphere,” and that there were “growing calls” in London to abolish the slave trade. These developments so alarmed American leaders that they declared independence from Britain in order to protect American slavery from British abolitionists. She does not explain how she came to this extraordinary insight, which has eluded the best historians of the last half century, nor does she offer the slightest evidence to support her claims.

Some of the nation’s leading historians have challenged these assertions as unsupported by evidence and wholly inconsistent with what we know about the development of antislavery thought in Britain. Rushing to her defense, the editor in chief of The New York Times Magazine, Jake Silverstein, responded that the colonists perceived a threat to slavery from a 1772 British judicial ruling, Somerset v. Stewart, in which the court held that slavery was not recognized in the English common law nor authorized by any statute governing the British Isles. Although the ruling applied only to Britain and had no bearing on slavery in the colonies, where slavery was authorized by statutes, Silverstein claims that it caused a “sensation” when it was reported in America and “joined other issues” driving the colonies toward independence.

The embarrassing spectacle of a newspaper magazine editor lecturing Gordon Wood, Sean Wilentz and other leading historians on the origins of the American Revolution would be mortifying if he wasn’t so spectacularly presumptuous and so clearly wrong. Somerset v. Stewart made barely a ripple in the American press. Six newspapers in the South published a total of fifteen short reports on the case, and two of the newspapers never reported the outcome. None of the reports expressed the slightest alarm, and no letter, newspaper essay, pamphlet or speech has been found in which a southern slave owner expressed anxiety about the Somerset case, much less that it “joined other issues” leading the colonists to declare their independence.

Nor were the British, as Hannah-Jones claims, “deeply conflicted” about slavery in 1776. British antislavery sentiment, such as it was, posed no threat to colonial slave owners. Its only conspicuous spokesman was Granville Sharp, who published A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery, the first British antislavery tract, in 1769. Sharp was responsible for bringing the Somerset case before the Court of King’s Bench. He had no more than a few allies. Lord Mansfield, who decided the case, delayed making his decision and when he did so, made it on narrow grounds. Other Britons shared Sharp’s distaste for slavery, but they were unconnected and did not constitute a movement of any sort.

The British abolitionist movement, as Christopher Leslie Brown, a professor of history at Columbia University, has demonstrated, took off after the American Revolution, drawing inspiration from the principles of the American Revolution and the abolition of slavery in the northern states, but above all shaped by the changed nature of the British Empire. As he explains in Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (2006), the first British scheme for the gradual abolition of slavery, A Plan for the Abolition of Slavery in the West Indies—an obscure proposal for the settling of free blacks in recently acquired West Florida—was published in 1772, the same year as the Somerset decision. It attracted no notice in Britain, much less America. During the American war and immediately afterwards, others suggested plans for an empire without slaves. Most were visionary schemes of no influence, but they constituted the first efforts to conceive of what emancipation might involve.

Nikole Hannah-Jones and Jake Silverstein didn’t discover the Somerset case nor link it to American independence on their own. Nor did they find it in Brown’s Moral Capital—a book that has enjoyed praise from scholars of slavery, the British Empire and the American Revolution. In a response to academic critics, Silverstein proudly asserted that Hannah-Jones was inspired by Slave Nation: How Slavery United the Colonies and Sparked the American Revolution (2005), by Alfred and Ruth Blumrosen, a book of no scholarly merit, but one that Hannah-Jones seems to have found congenial to her thesis.

Slave Nation, like “The Idea of America,” is a political polemic poorly disguised as history. Alfred Blumrosen was a professor at the Rutgers School of Law-Newark who specialized in employment discrimination. As a senior member of the staff of the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission in the 1960s, he pioneered the use of EEOC guidelines to support affirmative action to achieve racial equality in the workplace. By the 1990s he was frustrated by the pace of efforts to achieve racial equality in employment, and began advocating a more aggressive approach to mandate equal outcomes.

Alfred Blumrosen’s only venture into history, Slave Nation reflected his conviction that the United States is fundamentally racist and has been since its founding. It advanced the thesis that southern slaveowners were frightened into supporting independence by the Somerset decision. The Blumrosens managed to spin this argument into an entire book without citing even a single document in which a southern slaveowner expressed the slightest concern about the decision.

Slave Nation is a thin tissue of conjecture and speculation built on flawed assumptions, faulty reasoning and stubborn indifference to the need for evidence to reach rational conclusions. It was dismissed by every credible scholarly reviewer who examined it. The book is nonetheless energetically promoted by the “Zinn Education Project,” which is dedicated to spreading the ideas of the late Howard Zinn, a self-described anarchist and Marxist whose People’s History of the United States presents a relentlessly dark tale of xenophobia, brutality, racism (foisted on poor white laborers by the master class), poverty, hardened inequality and class divisions, misogyny, imperialism, corruption, and always and everywhere, capitalist greed papered over with hypocrisy.

Zinn rejected the possibility of objective truth and wrote history in the service of a socialist political agenda he never sought to disguise. He regarded the American Revolution as a vast fraud, in which rich Americans used the rhetoric of equality and universal liberty to secure their own interests and impose new mechanisms for class exploitation on unsuspecting Americans. “There is no such thing as impartial history,” Zinn wrote. Every description of the past, he insisted, “serves some present interest.” Zinn’s aim was never to equip his readers to understand the past. His goal was to persuade them to reject the present and embrace his vision for the American future.

Serious historians criticized Zinn for deliberately ignoring large parts of American history, distorting others and relying on unreliable sources, but this never gave him a moment’s pause. He wasn’t seeking truth about the past. He was crafting an interpretation of the past to serve his political agenda. He wasn’t writing for historians capable of seeing through his distortions and misinterpretations. He aimed his work at high school teachers and their students, seeking to indoctrinate the rising generation in his activist, ideologically charged brand of history.

Academic critics of the 1619 Project have been too gentle in their reaction to “The Idea of America” and its author. She belongs to a class of writers with no regard for historical truth, and whose ultimate purpose has nothing to do with understanding the past. Like Howard Zinn and Alfred Blumrosen, her purpose is wholly political. Like them, she makes assertions without evidence and ignores facts inconsistent with her arguments. And like them, her purpose is to undermine respect for the American Revolution and the fundamental principles that have shaped our history.

The irony of her “Idea of America” is that her outrage over the experience of African Americans is grounded in the principles articulated by the Revolution she condemns. She says the ideals of universal equality and natural rights expressed by the Revolutionaries were “false when written.” They were true then, as they are true now. They set slavery on the path to extinction. They are the foundation of progress and the basis of a better world.

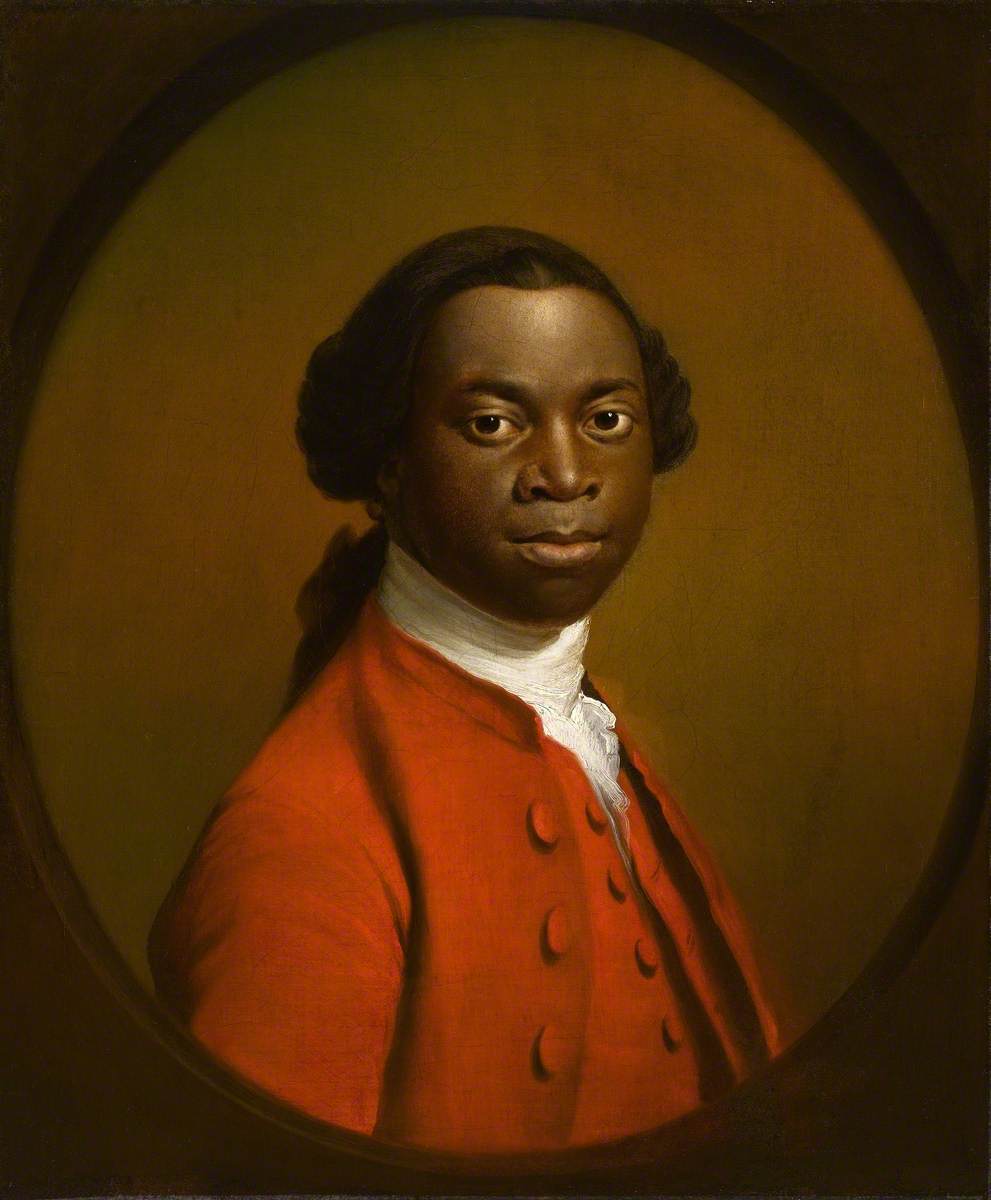

Above: The sitter in this ca. 1758 portrait attributed to Allan Ramsay is believed to be Ignatius Sancho. Born a slave, Sancho was later freed and became a successful London shopkeeper and writer.“When it shall please the Almighty that things shall take a better turn in America,” he wrote during the Revolutionary War, “when the conviction of their madness shall make them court peace—and the same conviction of our cruelty and injustice induce us to settle all points in equity—when that time arrives, my friend, America will be the grand patron of genius.” Royal Albert Memorial Museum. One of our readers, Professor Ibrahim K. Sundiata of Brandeis University, reminds us that the sitter has also been identified as Olaudah Equiano, an early black abolitionist, whose autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, created a sensation in London when it was published in 1789. It was the first important personal narrative of enslavement in English.

We encourage all our visitors to read Why the American Revolution Matters, our basic statement about the importance of the American Revolution. It outlines what every American should understand about the central event in American history. It will take you less than five minutes to read—and a few seconds to send the link to your friends, family, and colleagues so they can read it, too.

Read the companion essays responding the 1619 Project: “The American Revolution and the Foundations of Free Society” and “Slavery, Rights, and the Meaning of the American Revolution.”