The daguerreotype is the rarest and most immediate type of portrait of a Revolutionary War veteran, recording in a black-and-white photograph the faces of men and women who struggled for American independence. Introduced by French inventor Louis Daguerre in 1839, the daguerreotype was the most common photographic process of the late 1840s and 1850s. Few veterans of the Revolution lived into the age of photography, and even fewer had the means and opportunity to sit for a photographic portrait, making daguerreotypes of Revolutionary War soldiers quite rare. The Institute’s collections include six daguerreotypes of men who fought in the Revolutionary War, three of which are paired with daguerreotypes of their wives. One such pair depicts John Richard Watrous and his wife Lois Mather Watrous. These two daguerreotypes were conserved in 2019 in preparation for display in the Institute’s exhibition America’s First Veterans.

The daguerreotype is the rarest and most immediate type of portrait of a Revolutionary War veteran, recording in a black-and-white photograph the faces of men and women who struggled for American independence. Introduced by French inventor Louis Daguerre in 1839, the daguerreotype was the most common photographic process of the late 1840s and 1850s. Few veterans of the Revolution lived into the age of photography, and even fewer had the means and opportunity to sit for a photographic portrait, making daguerreotypes of Revolutionary War soldiers quite rare. The Institute’s collections include six daguerreotypes of men who fought in the Revolutionary War, three of which are paired with daguerreotypes of their wives. One such pair depicts John Richard Watrous and his wife Lois Mather Watrous. These two daguerreotypes were conserved in 2019 in preparation for display in the Institute’s exhibition America’s First Veterans.

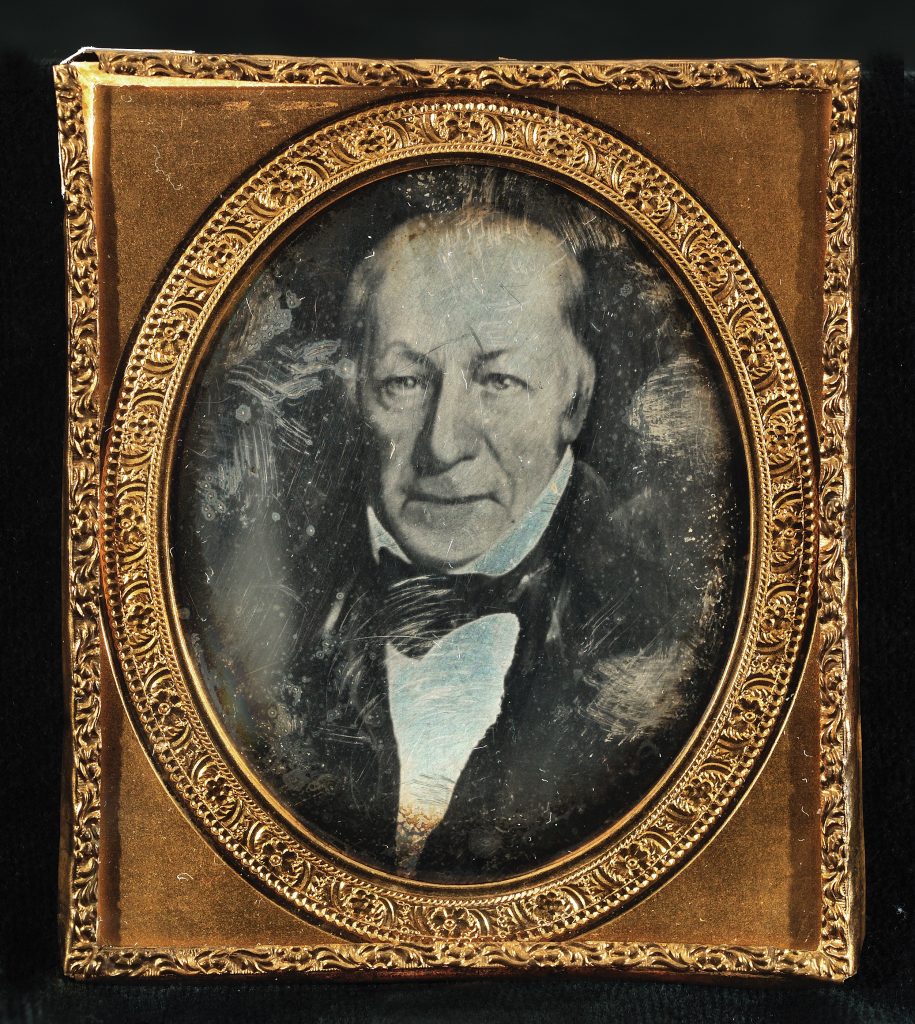

John Richard Watrous (1754-1842) of Colchester, Connecticut, was a surgeon in the Connecticut Continental Line during the Revolutionary War, serving from May 1775 until January 1783. He entered the military at the age of twenty-one as a surgeon’s mate in the Second Connecticut Regiment. On January 1, 1777, he was promoted to surgeon—a position he held for the rest of his service in the Revolution. After the war, Watrous returned home and worked as a physician, becoming a prominent member of the community and an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut. He married three times; the daguerreotype in our collections depicts his second wife, Lois (1776-1823), who married John Watrous sometime after 1797. Watrous was awarded a federal pension of twenty dollars per month under the Pension Act of 1818. Like thousands of other veterans, he was struck from the pension rolls two years later when Congress passed a new law restricting the qualifications for pensioners. Watrous’ compensation was restored in 1828 when an act of Congress provided Continental soldiers and sailors with full pay for life instead of a monthly pension. This income supported John Richard Watrous and his family until his death in 1842.

Early daguerreotypes captured images of living subjects, in addition to painted portraits and even other daguerreotypes to provide families with a compact and easily portable way to preserve and share images of other portraits of their relatives. The daguerreotype of Lois Watrous, who died sixteen years before the advent of photography, was taken of an earlier painted portrait. The source for the daguerreotype of John Watrous is less clear. The light reflections in the image suggest that it could be a daguerreotype copy of an original daguerreotype that was taken from life. Regardless, it is the only extant daguerreotype of an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati. The two daguerreotypes descended in the family to John Watrous’ great-great-great grandson Edmund Webster Burke, Jr., who donated them to the Society in 1975.

A daguerreotype presents a highly detailed image on a thin sheet of silver-plated copper. The copper plates came in standard sizes, which were referred to by their size in relation to the largest, or whole, plate. At 3 ¼” high and 2 ¾” wide, each Watrous image is a sixth-plate daguerreotype. The daguerreotype photographic process required great care. The copper plate was polished and treated with iodine vapors, then transferred to the camera in a lightproof holder. After the photographer took the image—an exposure could take up to fifteen minutes—the plate was developed over hot mercury, then immersed in a chemical solution to fix the image. The developed plate was encased behind a cover glass with a decorative brass mat that acted as a spacer between the plate and glass. This package was secured by a preserver—a thin brass binding that sealed the edges and prevented the developed plate from being exposed to air, which would erase the image. Daguerreotypes were commonly set in hinged cases for display and additional protection.

When the daguerreotypes of John and Lois Watrous were donated, they were paired together in a modern frame with a double-window velvet mat. At some point in the twentieth century, they were removed from their original cases to be installed in the frame. (The cases no longer remain.) Acidic paperboard was used as padding behind the daguerreotypes, and they were secured in the frame with cellophane tape. The toll taken by this reframing process, coupled with normal wear and tear over the life of the daguerreotypes, made conservation necessary before they could be exhibited.

The Watrous daguerreotypes were conserved in 2019 at Paul Messier Studio of Boston, a leading firm in the conservation of photographs and one of the few that specializes in treating daguerreotypes. The conservators and the Institute’s collections staff agreed on a conservative approach to the work considering the sensitive nature of the pieces. The two daguerreotype packages were first removed from the modern frame, which was retired. The plates were then removed from their preservers and mats and treated with puffed air on their front sides to remove loose dust and debris. After conservators removed tape and adhesive residue from all parts, they replaced the deteriorating original glass with new, stable borosilicate cover glass. (The original glass showed signs of chemical decomposition, resulting in a cloudy appearance and greenish tint that detracted from the image and would continue to worsen over time.) Conservators then resealed the plates, mats and glass with archival tape to prevent further air exposure. Mylar backings were also added to protect the otherwise exposed back of each plate. The original preservers were then returned, with that on the John Watrous daguerreotype having to be reinforced with a special sealing tape due to a tear in one corner. As a final step, the packages were placed in custom-made archival storage boxes in which they are housed when not on view.

View More Photographs in the Institute's Collections

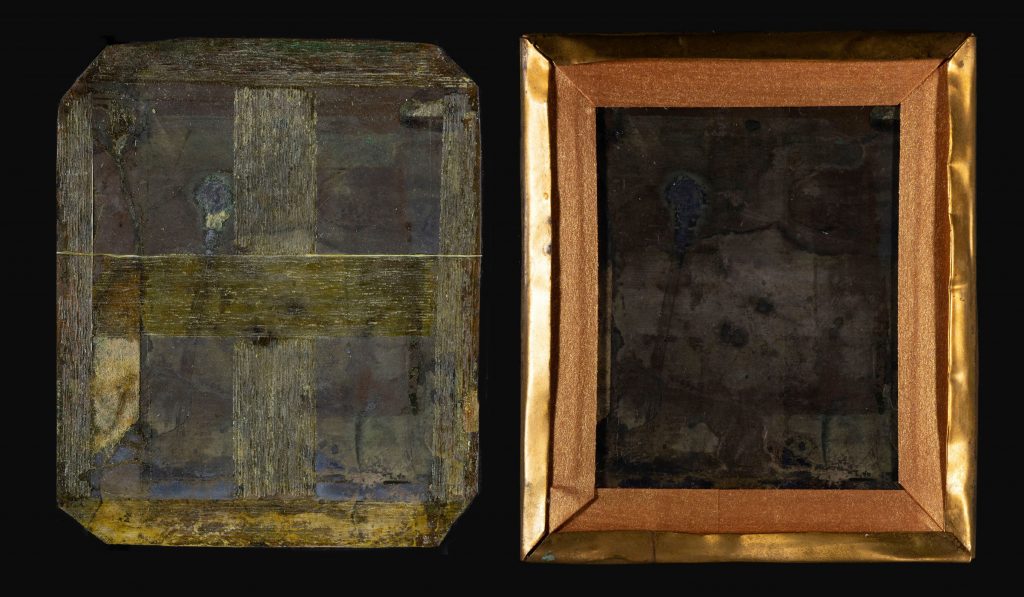

Daguerreotype of John Richard Watrous, before and after conservation

American

ca. 1840sGift of Edmund Webster Burke, 1975

The cloudy and discolored original glass obscured the daguerreotype image of John Richard Watrous before conservation (left). While conservators could not restore damage to the image itself, it is much brighter and crisper after cleaning and installation of a new stable cover glass (right).

Daguerreotype of Lois Mather Watrous, before and after conservation

American

ca. 1840sGift of Edmund Webster Burke, 1975

Replacing the deteriorating original cover glass and cleaning the daguerreotype plate brightened the image enough that details of the composition came through that were not very visible before conservation, like the portrait miniature of a man worn on Mrs. Watrous’ dress.

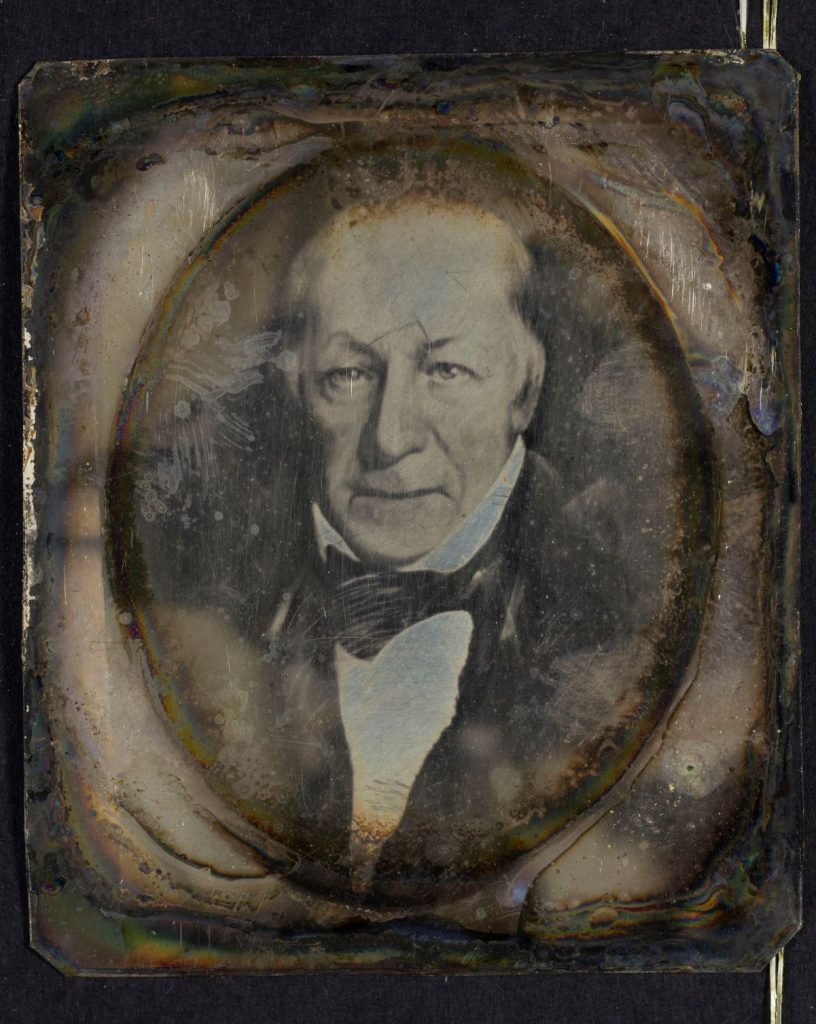

John Richard Watrous daguerreotype plate during conservation

The front surface of the John Richard Watrous daguerreotype plate exhibited old damage due to air exposure and abrasive attempts at cleaning, indicating that the sealed case had been opened at least once prior to the 2019 conservation treatment.