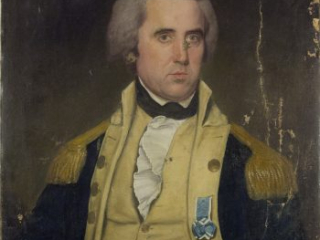

Portraits of unknown soldiers of the American Revolution are unfortunately common and can take decades, if not longer, to identify. One such painting in the Institute’s collections depicts an early American army officer wearing a Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia. When we acquired the unsigned portrait in 2010, the identity of the sitter was not the only thing that was hidden. The original paint surface—probably executed in the early 1790s—was languishing under layers of dirt and grime, extensive and discolored overpaint, flaking and lost paint and yellowed varnish. The canvas was also in poor condition, with old water damage, tears and cracks and the delamination (or separation) of the painting from a lining canvas threatening the stability of the artwork. Before we could fully assess who the subject of the painting was, it needed conservation to return the portrait as closely to its original appearance as possible.

Portraits of unknown soldiers of the American Revolution are unfortunately common and can take decades, if not longer, to identify. One such painting in the Institute’s collections depicts an early American army officer wearing a Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia. When we acquired the unsigned portrait in 2010, the identity of the sitter was not the only thing that was hidden. The original paint surface—probably executed in the early 1790s—was languishing under layers of dirt and grime, extensive and discolored overpaint, flaking and lost paint and yellowed varnish. The canvas was also in poor condition, with old water damage, tears and cracks and the delamination (or separation) of the painting from a lining canvas threatening the stability of the artwork. Before we could fully assess who the subject of the painting was, it needed conservation to return the portrait as closely to its original appearance as possible.

Paintings conservator Patricia Favero took on this challenging project, which lasted a total of fourteen months. Her initial assessment of the portrait identified both aesthetic and structural issues. The accumulation of dirt and grime was most noticeable on the officer’s face and torso—particularly his buff-colored waistcoat. Overpaint from an older conservation effort was scattered through the painting, especially in the background. The thick varnish coating applied by a previous conservator was dull, discolored and significantly deteriorating. The canvas itself was stiff, distorted and delaminating from an old lining canvas intended to support the picture. The canvas also bore a dark stain across the bottom of the painting, with cracked, flaking and lost paint throughout the same area—evidence of water damage at some point in the portrait’s past.

Removing the varnish and overpaint and cleaning the dirt and grime layers were the first steps in the portrait’s conservation. The overpaint applied during a previous restoration effort existed on top of the varnish layer—an important conservator’s technique to isolate later treatments from the original paint surface. The removal of these added layers resulted in what is called the “actual state” of the painting—the original paint surface, or as much as is left of it, with no additions or alterations by later hands. The actual state is as close as the modern viewer can get to the original image the artist created. This process revealed a gradation of color and light throughout the portrait—and a different shape to the officer’s nose—that was not apparent before the treatment. But cleaning also exposed numerous small areas where the original paint had been completely lost due to old water damage and tears—mostly running vertically in the right half of the painting.

Before the paint losses were addressed, the structural supports of the canvas had to be corrected. The lining canvas, which was probably added in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, was removed and discarded. Distortions in the original canvas and paint layer were relaxed using a heated suction platen—a device that applies controlled amounts of heat and moisture from the back of the canvas, then holds the canvas flat with gentle suction while it cools and dries. The treated canvas was re-stretched onto a new stretcher, as the existing wood stretcher was too damaged to reuse and was not original to the painting. A new loose lining of medium-weight linen provides added support for the original canvas.

The conservator then filled and inpainted the areas of lost paint to replicate their original appearance. The artist’s use of shadows and gradations of color provided clues to how these restored areas should appear. With a more deft and refined hand than her predecessors, the conservator built the image back up to its now-restored appearance. She finished the project by applying a stable, modern varnish to saturate the paint and supply an even gloss and richness to the portrait, as the original artist also would have done.

The mystery officer wears the uniform of a United States Army staff officer from the period of 1787 to 1800. The buff-and-blue uniform features a rise-and-fall collar, large gilt buttons and two gold bullion epaulets. A very similar uniform is depicted in portraits from the same period of William Irvine by Robert Edge Pine (ca. 1788) and of James Wilkinson by Charles Willson Peale (ca. 1796-1797). With no stars on the epaulets in our portrait, the mystery officer would have held the rank of major, lieutenant colonel or colonel at the time the portrait was painted. On his left lapel, he wears a Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia.

This officer was most likely an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati. His approximate age in this portrait is consistent with a man born about the mid-eighteenth century and old enough to have fought in the Revolutionary War. Hereditary members of the Society—although a small number were admitted as early as the 1790s—were few and far between in this period. And given his military service in the earliest years of the United States Army—the officers of which were almost exclusively veterans of the Revolution—it is unlikely he was an honorary member of the Society.

The American army of the 1790s was a fledgling group and rather limited in size. Its staff officers, who oversaw the army’s administrative departments, were even fewer in number. Nineteen staff officers from this period held an appropriate rank for the uniform in the portrait. Thirteen of those officers were original members of the Society—establishing an initial list of possible sitters. Among these men were numerous prominent officers whose portraits by John Trumbull, Charles Willson Peale, Ralph Earl, James Sharples and Charles B. J. F. de Saint-Mémin survive today. Comparing those likenesses with this portrait—although not an infallible process—whittled the list even further.

Research on these candidates conducted over several years by our curatorial staff and volunteers surfaced John Mills (1755-1796) as the most promising candidate for the sitter in this portrait. A native of Boston, Mills joined the American army as an ensign in Whitcomb’s Massachusetts Regiment in May 1775 and participated in the siege of his hometown. By the spring of 1777 he had been promoted to first lieutenant in the First Massachusetts Regiment. He fought with that unit later that year at Saratoga and the following summer at Monmouth Courthouse. Mills finished the Revolutionary War as a captain in Henry Jackson’s Additional Continental Regiment and was retained in the army until June 1784—nine months after the peace treaty had been signed. He became an original member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, as did his brother William. John Mills returned to military service in 1791 when he was commissioned a captain in the United States Army. He was promoted to major in 1793 and appointed acting adjutant general and inspector general in 1794—positions he held until poor health forced him to retire two years later. John Mills died in Cincinnati in July 1796.

Mills’ post-Revolutionary War military service took him west, where he distinguished himself under the command of General Anthony Wayne, a fellow member of the Society, in the war against the Northwestern Confederacy of Indians. Mills was also one of the original underwriters of the Ohio Company, a land company that settled communities primarily near Marietta. His final post was commander of Fort Greeneville, in present-day Ohio, where a treaty was signed in 1795 by Wayne and Indian leaders to end the war. With his relatively important military command and close ties to other original Society members, it is quite plausible that he would have desired a portrait commemorating those two aspects of his life.

In Mills’ will, he left property to his brother William Mills (1757-1812) and named as one of the executors Winthrop Sargent (1753-1820)—both fellow members of the Massachusetts branch of the Society. John Mills never married, nor did he have any children. Neither his will nor his brother’s contains a property list or mentions a portrait. William Mills had four children, but there is no surviving evidence any of them inherited a portrait of their uncle. If John Mills were the subject of the portrait, his lack of heirs may explain how the painting ended up descending outside of the family and how the identity of the officer was lost.

Assessments of the style of the portrait by two authorities on early American portraiture point to Joseph Wright (1756-1793) as the artist. Wright, a New Jersey-born artist who was trained in London during the Revolutionary War, spent more than a decade painting portraits of America’s founders, including original members of the Society of the Cincinnati. Hallmarks of the style of Joseph Wright, which are present in the Institute’s portrait, include the sitter’s upright pose, pale face, and long angular nose, as well as the heavy lines and shadows around the figure, especially in his chin, face and uniform.

Wright lived in Philadelphia from 1791 until his death in a yellow fever epidemic in September 1793. John Mills passed through Philadelphia numerous times in those years, when the city served as the American capital. Captain Mills spent most of March through December 1791 in Philadelphia as a recruiter for the Second U.S. Infantry. By May 1792, he was back in the city for a few months preparing to move troops west. Beginning in February 1793, Mills spent another two months in Philadelphia. This visit included a dinner with President George Washington on February 11 and Mills’ promotion to major eight days later. If Mills commissioned Joseph Wright to paint this portrait, it was most likely in early 1793 to mark his promotion to major before he returned west.

Before the portrait was conserved, our curatorial staff, as well as outside experts, thought it may be an early nineteenth-century copy of an unknown original. The details revealed by the conservation treatment confirmed that the portrait is an eighteenth-century original, attributed to Joseph Wright and very possibly depicting Major John Mills of the U.S. Army and Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati.

View More Paintings in the Institute's Collections

Portrait of an unidentified American officer

Attributed to Joseph Wright (1756-1793)

ca. 1791-1793Museum Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2010

Depicted after conservation was complete, this portrait depicts an officer of the U.S. Army with the rank of major, lieutenant colonel or colonel, and wearing the Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia suspended from a light blue ribbon.

Actual state

The cleaning process produced what is called the actual state of the painting—the original paint surface, or as much as is left of it, with no additions or alterations by later hands. The actual state is as close as the modern viewer can get to the original image the artist created.