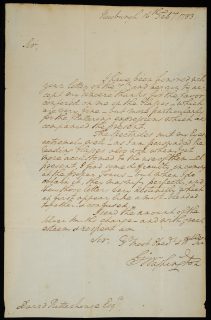

The address leaf, with part of the red wax seal still intact, from George Washington’s letter to “David Rittenhouse Esq., Philadelphia.”

From his headquarters at Newburgh, New York, on February 16, 1783, George Washington took time from his military duties to write a personal letter to David Rittenhouse thanking the Philadelphia inventor and instrument maker for a set of eyeglasses he had recently received. This private moment takes on striking historical significance when viewed in the context of the events that unfolded in the last months of the Revolutionary War.

When George Washington accepted his appointment as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in June of 1775, he was forty-three years old and in the prime of life and health. Countless contemporary descriptions of him emphasize his height and strength, and his majestic and commanding presence, especially on horseback. Just the year before, Silas Deane, a delegate to the Continental Congress, remarked in a letter to his wife that Colonel Washington retained “a very young Look, & an easy Soldierlike Air & gesture,” despite a military career that stretched all the way back to 1753. Washington was extremely protective of his public image, and he fiercely guarded his privacy. There is remarkably little in the surviving records about the state of the commander-in-chief’s health during the war. With the exception of a bout with quinsy, a throat inflammation, that laid him low for ten days at Morristown in 1777, and the beginnings of miserable dental problems that would plague him for the rest of his life, Washington seems to have been spared serious illness during this period. But the stresses and privations of the long war took their toll on his overall health—aging him beyond the eight chronological years he was away from home.

In January 1783, the war-weary general, now age fifty, quietly ordered a set of glasses to aid his dimming eyesight. While Washington is remembered as a man of action on the battlefield, he spent an enormous amount of his time at a desk reading and writing—tens of thousands of letters, orders, reports, maps and military manuals over the course of the war. On January 10, Washington mentioned in a letter to his aide-de-camp Tench Tilghman that he had sent a set of sample lenses that “suit his eyes” to David Rittenhouse to be used as the model for a new set that the Philadelphia instrument maker would grind and polish for Washington.

With this order, General Washington was seeking out the best. David Rittenhouse was renowned as an astronomer, mathematician and inventor, as well as a fine craftsman of scientific instruments. At the time of his correspondence with Washington he was a member of the American Philosophical Society and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was treasurer of Pennsylvania and later became the first director of the United States Mint. The quality of his work was already known to Washington, who had called on Rittenhouse’s services once before during the war—in 1778, when he asked him to repair a surveying instrument called a theodolite.

In early February Washington received two sets of spectacles—one for distance and one for reading—sent by Rittenhouse at no charge. Shortly thereafter the grateful general wrote to him to acknowledge the gift:

In early February Washington received two sets of spectacles—one for distance and one for reading—sent by Rittenhouse at no charge. Shortly thereafter the grateful general wrote to him to acknowledge the gift:

Newburgh 16th Feby 1783

Sir,

I have been honored with your letter of the 7th, and beg you to accept my sincere thanks for the favor conferred on me in the Glasses – which are very fine – but more particularly for the flattering expressions which accompanied the present.

The Spectacles suit my Eyes extremely well – as I am persuaded the Reading Glasses also will when I get more accustomed to the use of them – At present, I find some difficulty in coming at the proper Focus – but when I do obtain it, they magnify perfectly, and shew those letters very distinctly which at first appear like a mist – blended together & confused.

I send the amount of the Silver Smiths charge – and with great esteem & respect am

Sir, Yr Most Obedt & Hble Ser

Go Washington

These reading glasses would soon play a key role in one of the greatest challenges of Washington’s command.

The allied victory at Yorktown in 1781 had not ended the war. While the British still held New York City, Savannah and Charleston, a large contingent of the Continental Army under Washington’s command remained on duty, encamped along the Hudson River while waiting for the news of the treaty of peace that would allow them to go home. As the months stretched beyond a year, morale among the officers and men was faltering. Many had not been paid for months, or had been paid in paper money that was nearly worthless, and it was becoming increasingly clear that Congress lacked funds to support the promised half-pay for life. The commander-in-chief was well aware of the volatility of the situation. In October 1782, Washington wrote of his plans to stay in camp all winter “to try like a careful physician to prevent if possible the disorders getting to an incurable height.” As tensions escalated, Gen. Henry Knox formed a committee to gather and synthesize the officers’ grievances into an official memorial to Congress. The resulting petition was respectful but to the point: “The uneasiness of the soldiers for want of pay is great and dangerous; any further experiments on their patience may have fatal effects.”

The petition was presented to Congress on January 6, 1783, generating concern and sympathy but little action as the delegates debated the responsibilities of Congress versus the states in these matters. Washington keenly sensed how truly dangerous the situation within the army had become. In early March he confided to Alexander Hamilton, “The predicament in which I stand as Citizen & Soldier is as critical and delicate as can be conceived…. The suffering of a complaining Army on one hand, and the inability of Congress and tardiness of the States on the other, are the forebodings of evil.”

And then on March 10, General Washington was handed an unsigned notice calling a meeting of general and field officers for the next day, along with a transcript of the document now known as the first Newburgh Address. “The army has its alternative,” the anonymous document warned, suggesting that the officers might refuse to disarm when the war officially ended and might “retire to some unsettled country” and leave the United States and its Congress without an army. Shocked and deeply concerned, Washington immediately issued a general order condemning “such disorderly proceedings” and called for an official meeting of officers to be held at noon the following Saturday, March 15, in the newly constructed meeting hall known as the Temple of Virtue.

Washington had not planned to attend this gathering, asking Gen. Horatio Gates to preside, but a second anonymous address insinuating that by ordering the meeting Washington had signaled his support of the officers’ rebellion changed his mind. The most detailed and vivid account of Washington’s appearance before his officers on March 15 comes from a letter of Capt. Samuel Shaw, an aide-de-camp to General Knox, written to the Reverend John Eliot just a few weeks later. “[T]he unexpected attendance of the Commander-in-chief heightened the solemnity of the scene,” Shaw wrote. “Every eye was fixed upon this illustrious man, and attention to their beloved General held the assembly mute.” Washington, Shaw noted, “opened the meeting by apologizing for his appearance there, which was by no means his intention when he published the order which directed them to assemble. But the diligence used in circulating the anonymous pieces rendered it necessary that he should give his sentiments to the army on the nature and tendency of them.”

Asking “the indulgence of his brother officers,” Washington then read from a prepared address in which he implored them to recommit themselves to the great cause for which they had risked their lives and fortunes. He concluded, “Let me conjure you in the name of our common Country – as you value your own sacred honor – as you respect the rights of humanity; & as you regard the Military & National character of America, to express the utmost horror & detestation of the Man who wishes, under any specious pretenses, to overturn the liberties of our Country…. By thus determining and thus acting, you will pursue the plain & direct road to the attainment of your wishes…. You will give one more distinguished proof of unexampled patriotism & patient virtue, rising superior to the pressure of the most complicated sufferings.” It has been said that Washington was a better writer than he was a speaker, and although his remarks were strong and direct, his audience seemed unmoved when he finished.

To bolster his argument, Washington then read from a letter written by a member of Congress, Joseph Jones of Virginia, discussing the confederation’s severe financial distresses and assuring Washington of their “purest intentions” to secure “speedy and complete justice” for the army. Acknowledging the dangerous situation Washington faced at Newburgh, Jones wrote, “To you, it must be unnecessary to observe that when all confidence between the civil and military authority is lost, by intemperate conduct or an assumption of improper power, especially by the military body, the Rubicon is passed.”

The original manuscript of Washington’s address to the officers at Newburgh is now in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. It runs a full nine pages, carefully written out in his large legible hand. The original letter from Congressman Jones, dated February 27, 1783, is part of the Washington Papers at the Library of Congress—a closely written manuscript in a small cramped handwriting on which Washington has marked off the excepts he read to the officers. In recounting this moment of Washington’s appearance before the officers, Captain Shaw wrote:

One circumstance in reading this letter must not be omitted. His Excellency, after reading the first paragraph, made a short pause, took out his spectacles, and begged the indulgence of his audience while he put them on, observing at the same time, that he had grown gray in their service, and how found himself growing blind. There was something so natural, so unaffected, in this appeal, as rendered it superior to the most studied oratory; it forces its way to the heart, and you might see sensibility moisten every eye. The General, having finished, took leave of the assembly.

As Washington left the hall, General Knox took control of the meeting, offering a motion to thank the commander-in-chief for his address and assure him of the officers’ affection, which passed easily. A report of the officers’ earlier petition to Congress followed, along with proposals drawn up by Knox and Lt. Col. John Brooks affirming that the army would undertake no conduct that would sully its reputation and expressing confidence in Congress, while at the same time exhorting Washington to keep up the pressure for the army’s relief. The anonymous addresses were rejected “with disdain.”

With the threat of mutiny effectively dispelled, Henry Knox seized the renewed sense of unity to move forward with his longstanding idea for an organization that would perpetuate the feeling of brotherhood among the officers and commemorate the achievements of the war. He envisioned a society with a membership of the whole officer corps, and by April 15 he had produced an eight-page draft outlining its mission, purpose and structure. Knox’s proposals for the organization were circulated, vetted and revised, until finally, on May 13, 1783, a group of officers meeting at General Steuben’s headquarters, across the river from Newburgh at Mount Gulian, adopted the Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati. Their first act was to have their founding document inscribed on a large sheet of parchment that was taken to General Washington with a request for his approval and signature.

Significantly, all of the officers believed to have been involved in what is called the Newburgh Conspiracy ultimately joined the Society of the Cincinnati, committing themselves to its Immutable Principles. Washington’s clear vision of a patriot army subordinate to civilian rule had prevailed.

The letter of George Washington to David Rittenhouse, February 16, 1783, is the gift of George Miller Chester, Jr. (Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut) in honor of his great-great-great-great grandfather, Col. John Chester (Yale 1766), Sixth Regiment, Connecticut State Troops in Continental Service, an Original Member of the Society of the Cincinnati.

See the letter in the Institute’s Digital Library.

View More Manuscripts in the Institute's Collections