Click to download the catalog.

The American Revolution marked the beginning of an age of democratic revolutions that swept over France and challenged the old order throughout the Atlantic world. The French officers who served in the American War of Independence, whether as idealistic volunteers or resolute soldiers of their king, remembered the experience for the rest of their lives. Many preserved their reflections on the revolution in America in daily diaries, private journals and carefully composed memoirs, leaving us with a remarkable array of perspectives on America, Americans and the first act in the age of revolution.

None of them could have foreseen that the war for America was a prelude to an even greater upheaval that would transform France. The astonishing turmoil of the French Revolution shaped and colored memories of the war for America. For some, the American war was a distant reflection of their unshakable loyalty to their martyred king. Others cast themselves as chroniclers and historians of the American war, recognizing that they were witnesses to events that had changed their world. For the most visionary, the war for America was the first stage in an international struggle for liberty. Together their reflections remind us that historical memory is fragile, always shifting, and often very personal.

Drawn from the Institute’s collections, along with loans from private collections, Revolutionary Reflections features the written reflections of eight French officers paired with life portraits of the writers and other artifacts that enrich our understanding of their experiences in America. Among the treasures on view is the original manuscript memoir of General Rochambeau, who commanded the largest French army sent to America, along with his family’s annotated copy of the published work—neither of which has ever been displayed before. The exhibition reunites the manuscript journals and other writings of François-Ignace Ervoil d’Oyré, a captain in the royal corps of engineers with Rochambeau’s army, with his oil portrait painted late in life by French artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze (The Schorr Collection). An oil portrait by Spanish master Vicente López y Portaña of the marquis de Saint-Simon, who commanded 3,500 French troops at Yorktown, appears with his manuscript journal of the campaign (Collection of Comte Patrick de Rouvroy de Saint-Simon). The show also includes examples of the Society of the Cincinnati’s Eagle insignia and membership certificate owned by French officers—symbols of their participation in the fight for American independence and reminders of their lasting ties to the new United States.

Louis Seize, Roi des Français, Restaurateur de la Liberté

Jean-Guillaume Bervic, engraver, after Antoine François Callet, artist

Paris: Felix Hermet, ca. 1880sThe Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Paul A. Rockwell, 1959

The officers of the French army and navy, drawn almost entirely from the aristocracy, saw the war for America as an opportunity to serve their king, restore the honor of France and win distinction for themselves. Louis XVI, who ascended to the French throne in 1774 at the age of twenty, is depicted in his coronation robes in this engraving originally printed in 1790. The copperplate was broken during the French Revolution but restored in the nineteenth century, when additional impressions, such as this one, were made from it.

Allegorical portrait of Thomas François Lenormand de Victot

Nicolas René Jollain (1732-1804)

1783The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2010

French memories of the war for America were reflected in the way families honored their dead. Thomas François Lenormand de Victot, a lieutenant de vaisseau in the French navy, served in the Caribbean under Admirals d’Estaing and de Grasse. Shortly after Lenormand de Victot died of disease at Fort Royal on Martinique in April 1782, his family commissioned this dramatic allegorical portrait to memorialize his sacrifice. The oil painting depicts the fallen French officer’s spirit standing between Death and wounded sailors, who are receiving their last rites—with Fort Royal and de Grasse’s fleet in the background.

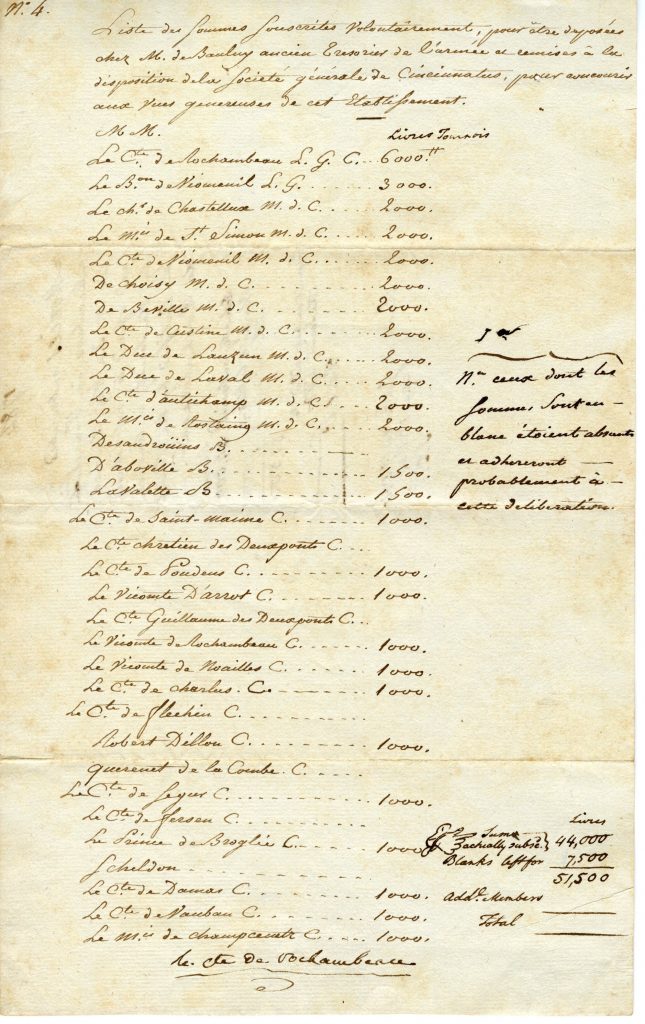

“Liste des sommes souscrites volontairement, pour … la disposition de la Société générale de Cincinnatus”

January 19, 1784The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

In 1784 French officers who served in America formed the Société des Cincinnati de France, a branch of the hereditary order founded in New York the previous year. The Society’s Institution required that members contribute one month of their military pay to support its activities. Within days of the first provisional meeting to organize the French branch in January 1784, more than thirty French officers—including Rochambeau, Chastellux, Saint-Simon and Dillon—had pledged to donate 51,500 livres to the General Society.

Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia owned by Louis François Bertrand du Pont d’Aubevoye, comte de Lauberdiére

Nicolas Jean Francastel and Claude Jean Autran Duval, Paris

1784The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2013

The first examples of the iconic Society of the Cincinnati insignia, known as the Eagle, were made in Paris in January 1784 for French members of the Society. Popular among French officers and admired by their countrymen, the Society Eagle symbolized their service to their king and association with the American war and its revered leader, George Washington, who was the Society’s first president general. The gold-and-enamel badges were first distributed by the marquis de Lafayette, at whose Paris home the first meeting of the Société des Cincinnati de France took place.

Journal of Robert-Guillaume, baron de Dillon

Covering the period 1780-1781The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Rémy Galet-Lalande, 2014

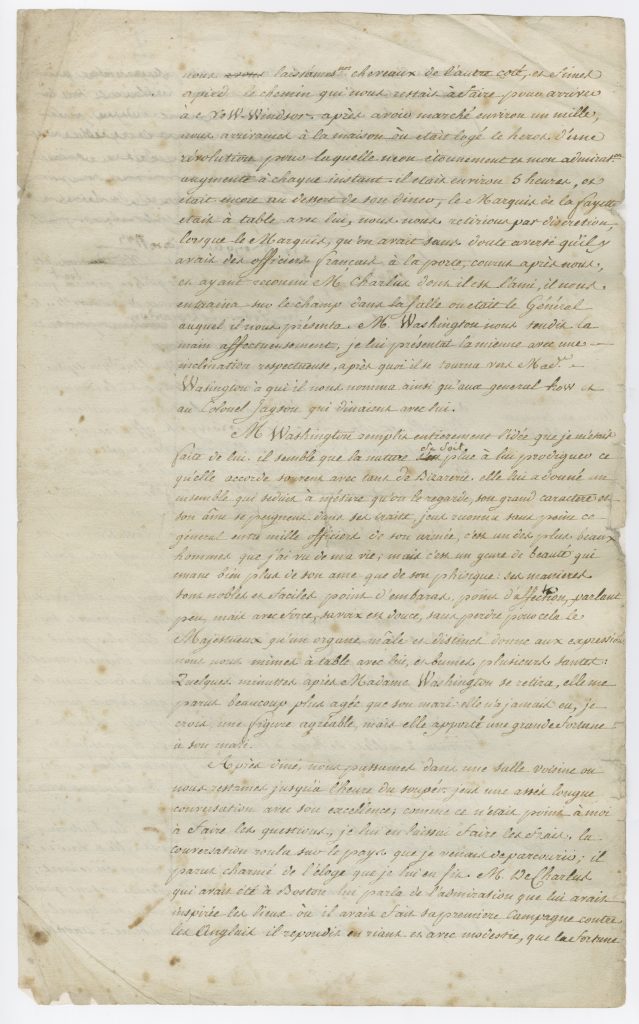

Dillon was a colonel in Lauzun’s Legion, an elite volunteer cavalry regiment that served in America as part of Rochambeau’s expeditionary force. Dillon's manuscript journal covers the period November 1780 through the siege of Yorktown. During his travels in America he recorded candid observations of the people he met. Upon seeing General Washington for the first time, Dillon wrote, “I recognized without difficulty the general out of a thousand officers of his army, he was one of the most handsome men that I’ve seen in my life.”

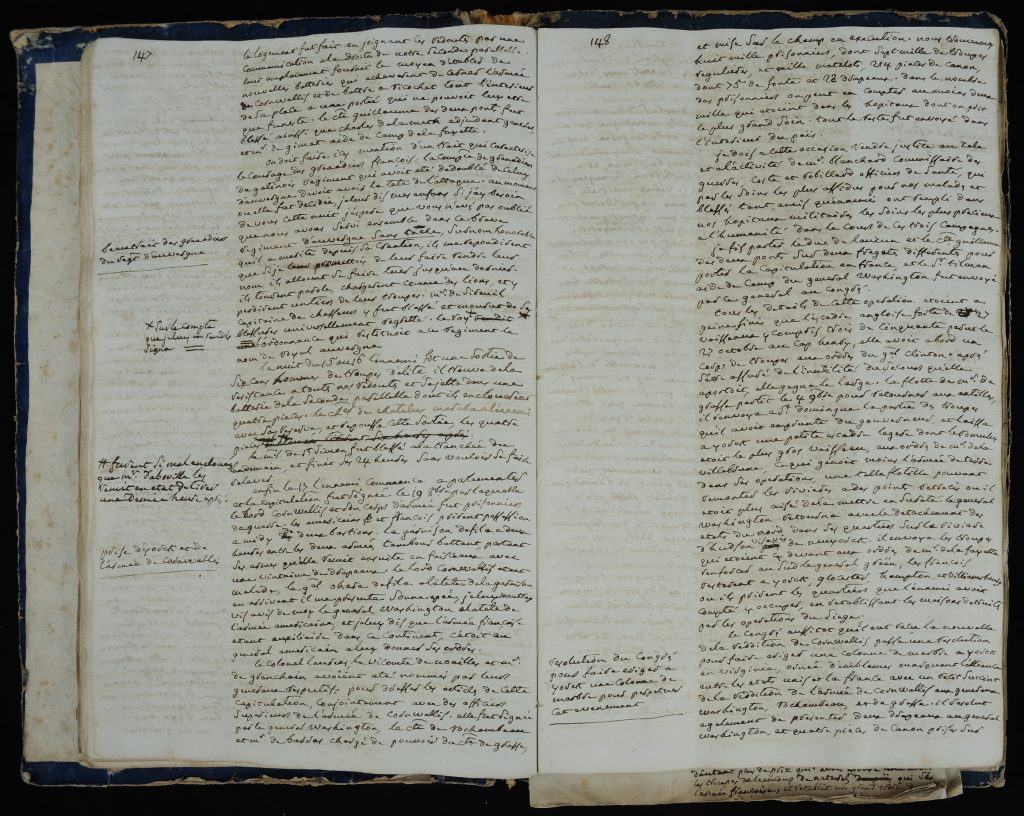

“Notes Relatives aux mouvemens de l’armee françoise en Amerique”

François-Ignace Ervoil d’Oyré

Covering the period 1780-1783The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

François-Ignace Ervoil d’Oyré was a captain in the royal corps of engineers when he arrived in America with Rochambeau’s army in July 1780. At Yorktown, Oyré played an essential role in the planning and conduct of the siege. After his return from America, Oyré transcribed his notes of his wartime experiences into five small notebooks. These experiences include a visit to Mount Vernon with Washington and Rochambeau during the French army’s march from Newport to Yorktown in the summer and early fall of 1781.

Voyages de M. le marquis de Chastellux dans l’Amérique Septentrionale dans les Années 1780, 1781 & 1782

François-Jean de Beauvoir, marquis de Chastellux

Paris: Chez Prault, Imprimeur du Roi, 1786The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Timothy W. Childs, 1983

From the moment he arrived in America as Rochambeau’s second in command, Major General Chastellux took a keen interest in the people and country whose fight for independence they had come to aid. This two-volume account of his American experience, published a few years after the war, includes an engraving of Natural Bridge, a geological wonder in Virginia that he visited after the Siege of Yorktown.

“Journal des differentes campagnes que j’aÿ fait soit par terre ou par mer”

Jean-Baptiste Dupleix de Cadignan

Covering the period 1754-1785The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

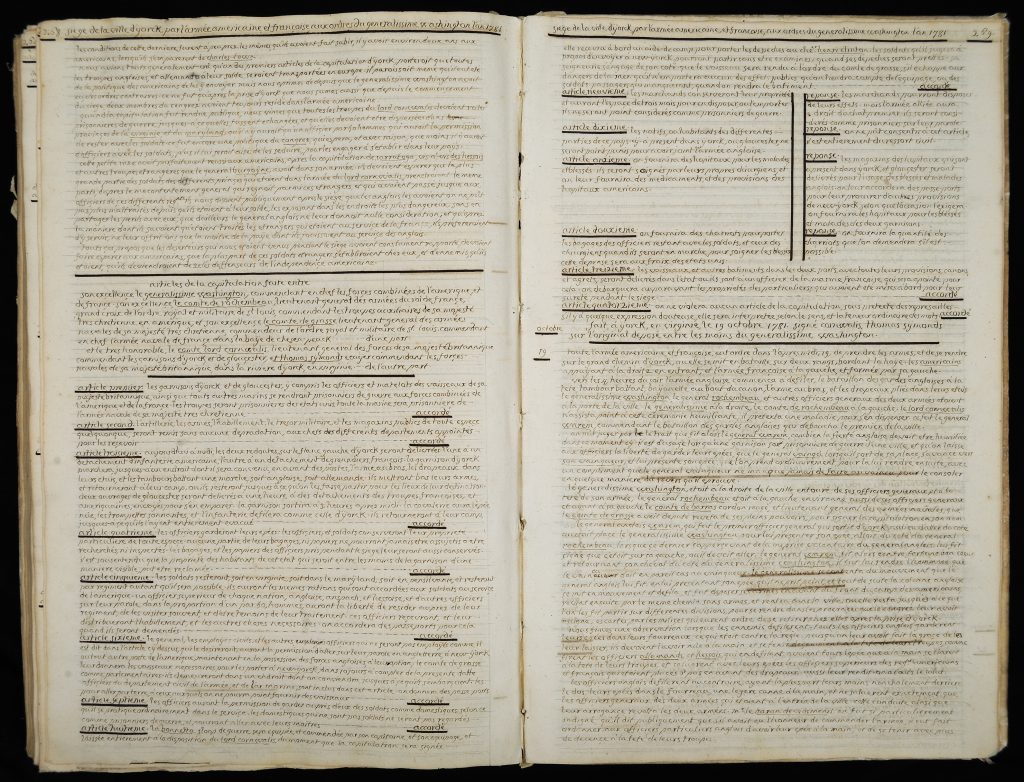

Dupleix de Cadignan’s two-volume journal covers his military career over nearly thirty years, including more than three hundred pages on the American Revolution. His day-by-day account of the Siege of Yorktown includes a full transcription in French of the Articles of Capitulation and a detailed description of the surrender ceremony. Drawing from personal notes, logbooks, official reports and contemporary histories, he produced a meticulous chronicle of the war and refrained from expressing his personal opinions about the events.

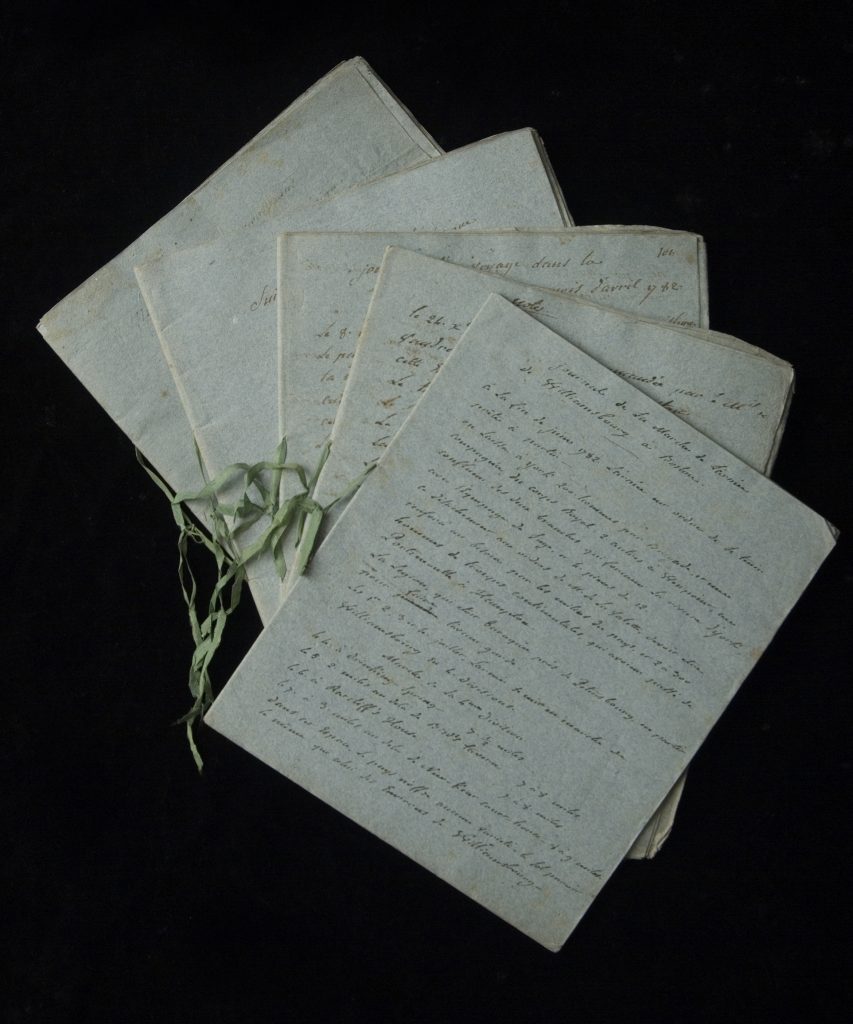

“Journal tenu par Henri Dque. de Palys, Chevalier d’Montrepos pendant son voyage en mer, pour aller en Amerique, 1780-1783”

Henri-Dominique, chevalier de Palys de Montrepos

Covering the period 1780-1783The Society of the Cincinnati, Purchased with a gift from a private foundation, 2014

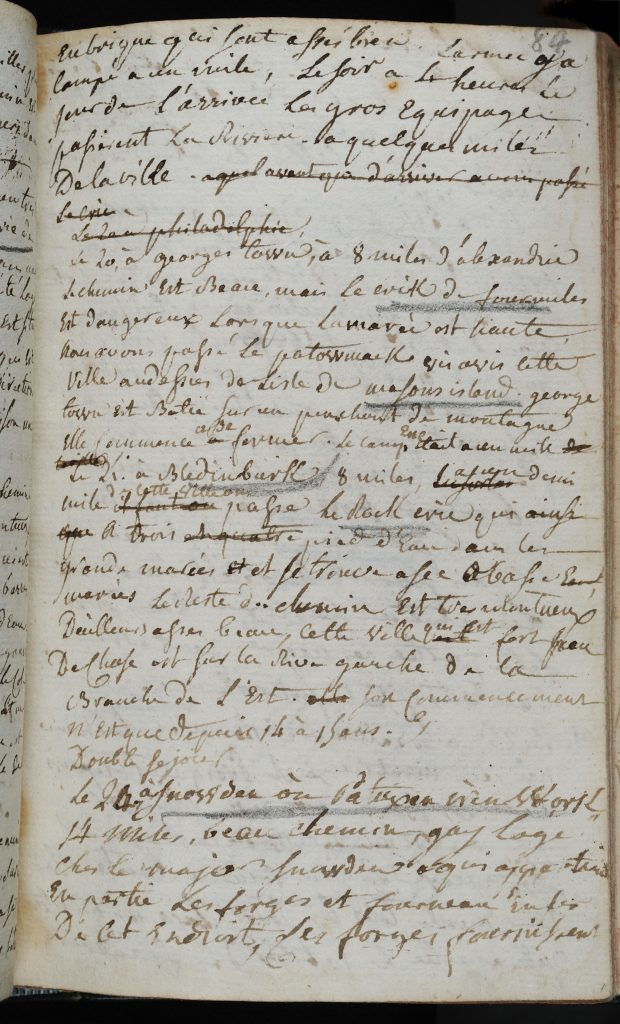

An officer in the royal corps of engineers, Palys de Montrepos kept a diary of his voyage across the Atlantic from France to America, the French army’s residency in Newport, Rhode Island, and their subsequent march to Yorktown in 1781. Although he made no entries during the Yorktown siege, he picked it up again to document the army’s return march from Virginia to Boston for their departure for France. On July 20, 1782, he noted that his division crossed the Potomac River at Georgetown and camped about a mile from town—in the vicinity where the American Revolution Institute’s headquarters now stands.

La Tableau Moral Raisonné des Symboles de la République

Nürnberg: Joh. Andreä Endterische Handlung, ca. 1794The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The expenses of the American war drove the French government to insolvency, hastening the outbreak of revolution in 1789. This print reflects the radical transformation of the French Revolution that began in the summer of 1792. Allegorical figures of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity—the optimistic motto of the French Revolution’s first years—are joined by Unity and Indivisibility, the added watchwords of the radical Jacobins who imposed political orthodoxy, and violence, through the Terror. The print includes George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and other classical and Enlightenment “founders of liberty,” alongside nine French leaders of the Revolution who had died in battle, or by assassination, execution or suicide, as “martyrs of liberty.”

“Manuscript des memoires politiques et militaires du Marechal de Rochambeau”

Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau

Covering the period 1725-1807The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of the Rochambeau family, 2016

Rochambeau’s manuscript memoir covers the full span of his life, from his education and early military service during the War of Austrian Succession right up to the month of his death. He wrote it in his retirement after the French Revolution, reflecting on his experiences over seven decades of war and political transformation. Fifty pages are devoted to his account of leading the French expeditionary force in America. He paid special attention to the end of the Revolutionary War, closing the scene with an account of Washington’s resignation of his commission at Annapolis, the exemplar of military authority subordinate to civilian rule that had not been replicated in Rochambeau’s lifetime.

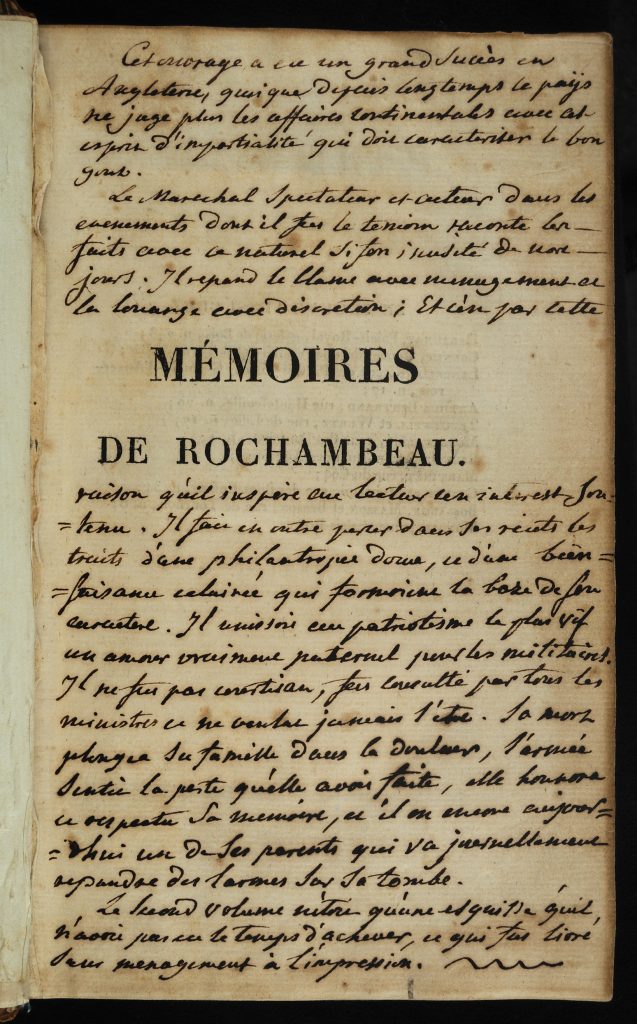

Mémoires Militaires, Historiques et Politiques de Rochambeau

Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau

Paris: Chez Fain, imprimeur, 1809The Society of the Cincinnati, Purchased with a gift from a private foundation, 2016

In his will, Rochambeau directed his wife to have his manuscript memoir edited and published after his death. She engaged the services of Luce de Lancival, a well-known poet and playwright, who produced a two-volume edition of the Memoires in 1809. This copy bears the annotations of Rochambeau’s son, Donatien, a military officer who had served under his father in America.

Claude-Anne de Rouvroy, marquis de Saint-Simon-Montbléru

Vicente López y Portaña (1772-1850)

ca. 1815-1818The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2018

Saint-Simon was a maréchal de camp—the equivalent of a major general—commanding French troops in the West Indies and at the Siege of Yorktown during the American Revolution. A fierce royalist, he emigrated to Spain in 1792 and led troops against the French revolutionaries and, later, against Napoleon. In this oil portrait, Saint-Simon wears a Spanish army uniform with the blue-and-white sash and star of the Order of Charles III, the highest Spanish military honor of the time, as well as the cross of the French military order of Saint Louis and the insignia of the Society of the Cincinnati, of which he was an original member.

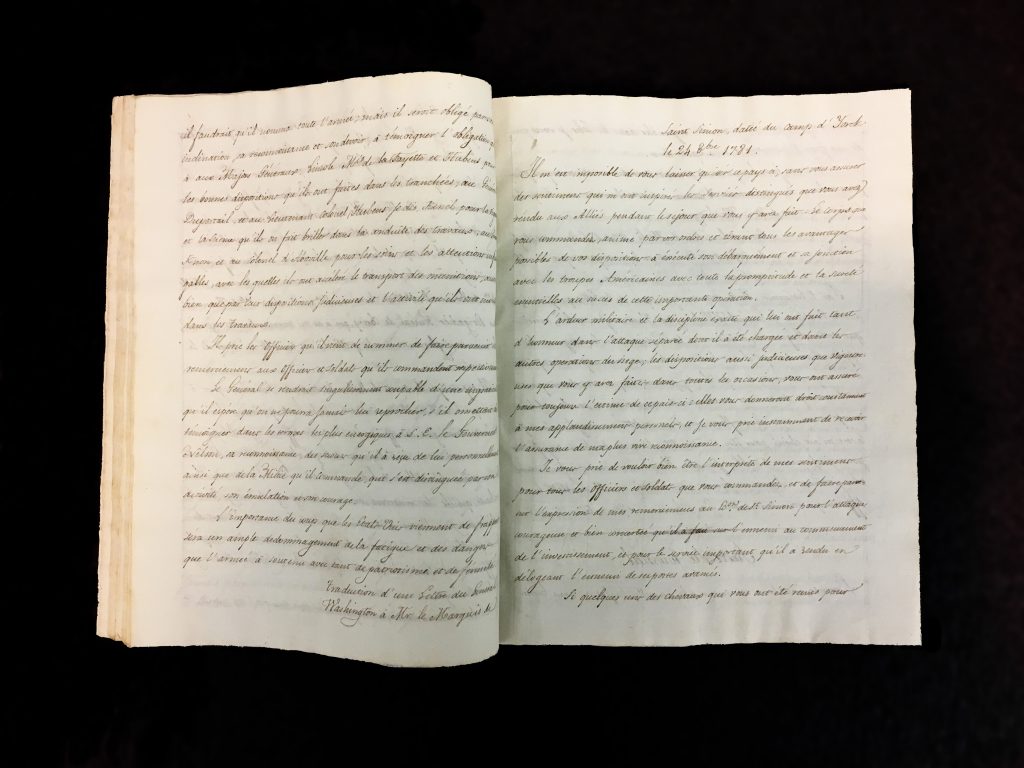

“Journal de la campagne des etats unis d’Amérique dépuis le 5 Juillet 1781 jusqu’au 12 Avril 1782”

Claude-Anne de Rouvroy, marquis de Saint-Simon-Montbléru

Covering the period 1781-1782Courtesy of Comte Patrick de Rouvroy de Saint Simon

Saint-Simon’s journal of his campaigns in America is the strict record of a stern professional soldier, without comment on America or the American cause. His account of the Siege of Yorktown—during which he commanded the left flank of the allied troops—features statistics on the strength and casualties of French regiments, a daily account of the allies’ gradual advance on the British lines, and even footnotes to provide more explanation. It also includes a French translation of a letter Washington wrote to Saint-Simon on October 24, 1781, offering his gratitude for Saint-Simon’s leadership at Yorktown and for the “military ardour and perfect discipline” shown by his men.

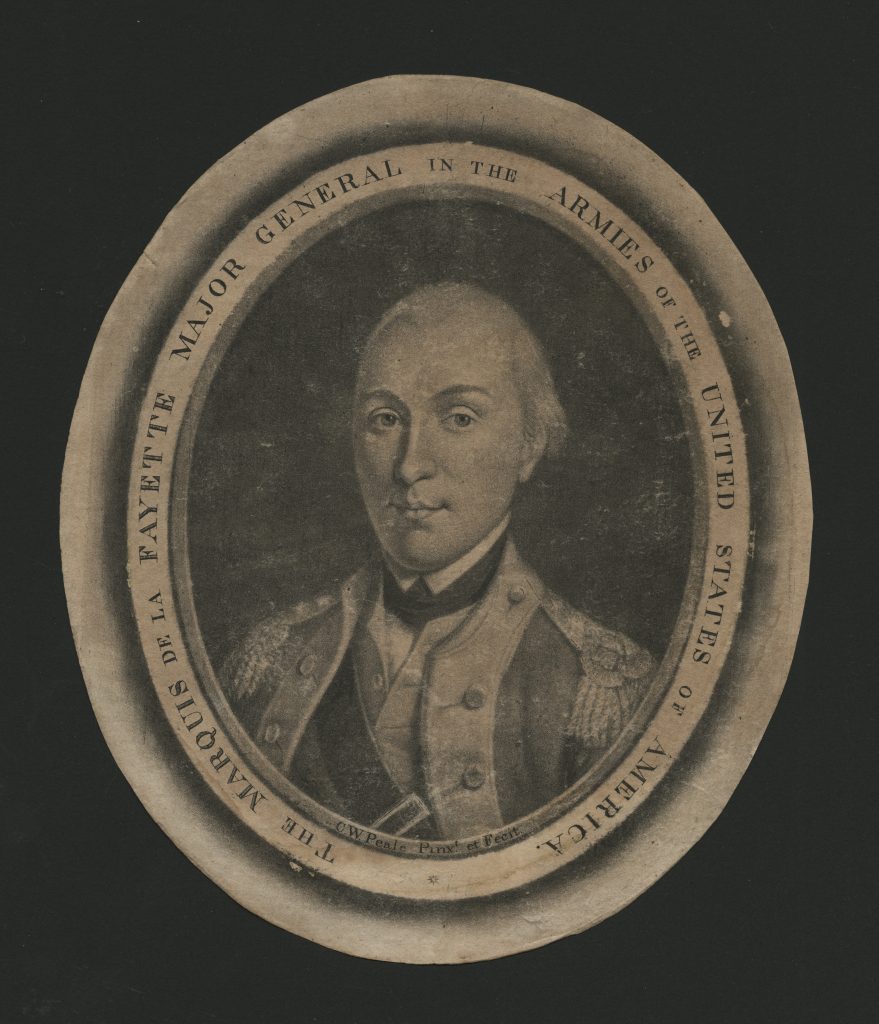

The Marquis de La Fayette Major General in the Armies of the United States of America

Charles Willson Peale, artist and engraver

Philadelphia, 1787The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

During the American Revolution, Lafayette became one of General Washington’s most trusted officers, an international hero and a champion of liberty. This mezzotint, based on Charles Willson Peale’s life portrait of Lafayette in 1780, captures the direct gaze of the idealistic young major general in his Continental Army uniform.

Marquis de Lafayette commemorative medal

Rambert Dumarest, artist

Struck in France, 1789The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Lafayette welcomed the French Revolution as an opportunity to secure the kind of liberty for France that he had fought for in America. He became commander of the Paris National Guard the day after the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, sending the key to the fallen prison to George Washington “as a missionary of liberty to its patriarch.” This bronze medal commemorates Lafayette’s leadership of the city’s militia—a position he held for two years. The obverse bears a portrait of Lafayette wearing a French military uniform, and the reverse features the coat of arms of Paris and a banner above with the motto, “Vivre Libre ou Mourir.”

General Lafayette at the Anniversary of the Battle of York Town, Oct. 19, 1824

William Russell Birch (1755-1834) after Ary Scheffer (1795-1858)

ca. 1824-1834The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of the Friends of the Boush-Tazewell House, Inc., 1991

Exactly forty-three years after the British surrendered at Yorktown, Lafayette returned to the battlefield while on his tour of the United States in 1824 and 1825. A crowd of more than ten thousand greeted the French hero. Recalling their triumph decades earlier, Lafayette dined on the battlefield with fellow war veterans under George Washington’s headquarters tent. This portrait of the French general—painted in enamel rather than watercolor, to be more durable and less expensive than typical portrait miniatures—was a souvenir of the Yorktown celebration.