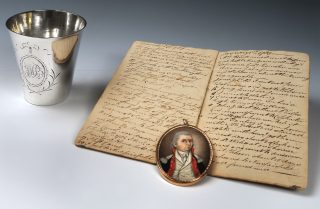

Few wartime diaries of Continental officers survive. Among the treasures of the Society of the Cincinnati is the diary of John Hutchinson Buell (1752-1813), an officer in the Connecticut Continental line and original member of the Connecticut Society who later served as an officer in the United States Army, together with a portrait miniature of Buell and a small silver beaker bearing his initials.

The diary begins in June 1780. It consists of thirty-seven pages sewn into a paper cover. The inside cover bears the notation “John Buell Bought in Philadelphia 23 October 1776.” The folded sheets that make up the diary are rather loose in the cover, suggesting that the little book once included a gathering with entries for 1776-1780. If so, the earlier section was missing as early as 1887, when the surviving portion was privately printed as a pamphlet in Brattleboro, Vermont, by the short-lived partnership of Hildreth & Fales.

By the summer of 1780 the British had largely abandoned offensive operations in the North. Troops had been detached from Clinton’s army to defend the Caribbean and to mount an offensive in the Carolinas. The British took Charleston in May 1780 and with it, the only substantial Continental force in the South. Washington’s army was encamped in a broad arc from the east side of the Hudson across from West Point to Morristown, New Jersey, with outposts to the south, containing the British within their fortified lines surrounding New York City. The value of Continental currency had collapsed, and with it had gone the ability of the quartermasters to provision and supply Washington’s army. Buell and his regiment had spent the winter and spring at Morristown.

“We left the huts at or nigh Morristown,” Buell wrote on June 6, 1780, “in consequence of the Enemy’s being out at Springfield. The first night we got to Short Hills. Springfield was then in flames.” Through the summer and fall the army maneuvered outside New York City, gathering supplies and denying the British the same opportunity. At the end of July, Buell recorded that the departure of the British fleet from New York Harbor occasioned a flurry of activity. “The Gen’l was determined to attack York,” Buell wrote, “and preparations were made for it, but the fleet returned, which prevented.”

The diary documents the routine of life for a Continental Army captain: leading his company on marches and countermarches, gathering forage and provisions, rumors of British activity, news of duels, courts martial, and socializing with brother officers, as well as the proud moments of an officer’s career, including his appointment to command his regiment’s light infantry company and receiving a sword as a gift from its maker. It also reveals the extent of Buell’s opportunities to socialize with family and friends who lived within a day or two of camp.

Buell and his company spent the winter of 1780-1781 at Connecticut Village, an encampment on the east bank of the Hudson River, opposite West Point. As its name suggests, it was occupied by units of the Connecticut Continental line. He enjoyed two months leave in midwinter, which he spent visiting and courting, particularly at “Esq. Hubbell’s” in Fairfield County. He returned to camp in February, noting in his diary on April 6: “I dined at Genl. Washington’s.” Three times that spring, he got away from camp to visit the home of Ephraim Hubbell, where Hubbell’s daughter Phebe was the object of his attention.

During the summer of 1781 Buell was detached for service with a company of boatmen, ferrying troops back and forth across the Hudson River. Between August 21 and 27 he worked to get Rochambeau’s army across the river on its march toward Yorktown. Remaining behind with the troops under the command of General William Heath, Buell did not make the march to Yorktown. Indeed he was on a forty-day furlough, visiting relatives and friends in Connecticut, when the British surrender occurred.

On November 18 he reported happily: “Miss Phebe and I went to meeting and were publish’d,” meaning their plans to marry were announced. Buell returned to camp the next day, but traveled to Connecticut a few weeks later. On December 13, with several brother officers in attendance, Buell and Phebe were married. Two days later, Buell recorded that the gentlemen held a men-only party, where they “spent the evening in a high, (too high), rakish way, drinking wine, etc.” til past midnight. On the way home that night, Buell overturned the sleigh he was driving.

During 1782 Buell remained with his regiment on the Hudson, but made frequent short trips to Fairfield to spend time with Phebe. As peace negotiations moved slowly forward, officers worked to maintain discipline in the army. The highlight of the year was clearly the grand review held for General Rochambeau on September 12, which Buell described in detail. He sought to leave the service in November, but Gen. Jedediah Huntington insisted that he remain.

Buell brought Phebe back to camp with him in February 1783. She remained with him through the spring, and was there when peace was announced on April 19. Buell finally received permission to retire in May, and the couple set out for Fairfield on June 10. They spent the summer with Phebe’s father and stepmother, but in September Buell set to work repairing an old house in Hebron for the two of them. In November Phebe gave birth to their first child. The diary closes on January 14, 1784, with this entry: “We got into our own House.”

The diary, portrait miniature and a silver beaker engraved with Buell’s initials descended in Buell’s family through his daughter Gratia T. Buell Hollister. The beaker may have been made by Alexander Vuille of Baltimore around 1795. It was part of a larger set Buell owned. Another beaker, a cup, and a ladle engraved with the same cipher are in the collections of the Yale University Art Gallery. Together the three items in this little collection illuminate, in a very personal way, the career of an officer who spent much of his life serving our republic.