“Beneath all the fanfare, like a steel wire inside a silken thread, runs a kind of life-or-death awareness that foreign policy is made by human beings, with feelings that can be soothed or flattered, bruised or lacerated.” Wiley T. Buchanan, Jr., U.S. Chief of Protocol, Red Carpet at the White House (Dutton, 1964)

From the time our country began to assert itself as an independent state, America has actively engaged in the delicate art of diplomacy, from Benjamin Franklin’s diplomatic work in the 1760’s to the essential diplomatic business of the present day—negotiating peace, global security, trade, and human rights; convening summits and multilateral meetings with our international neighbors; hosting official State visits and swearings-in of our nations diplomats; and, celebrating the accomplishments and contributions of global citizens, both foreign and domestic. In his 2014 State of the Union Address, Barack Obama reminded Americans that: “In a world of complex threats, our security and leadership depends on all elements of our power—including strong and principled diplomacy.” This lesson investigates the evolution of American diplomacy and asks students to research an individual who served a local, state, regional or national cause as a diplomatic ambassador, and then consider how they, too, might engage as a civic ambassador for a cause dear to their community.

Suggested Grade Level

Elementary and Middle School

Recommended Time Frame

Three fifty-minute sessions

Objectives and Essential Questions

Students will:

- understand the definition of diplomacy and the role of diplomatic service in a republic;

- recognize Benjamin Franklin’s invaluable contributions to the cause of American liberty—particularly in France—and the exemplary standard for diplomatic service to country Franklin created;

- investigate historical and contemporary individuals who selflessly represent a cause in the republican tradition of Franklin; and

- consider how they might serve as a civic ambassador for a cause dear to their community.

Materials and Resources

(in order of appearance)

- The Examination of Doctor Benjamin Franklin, before an August Assembly, relating to the Repeal of the Stamp-Act, &c. Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons [Boston: reprinted by Edes and Gill, 1766?]. The Massachusetts Historical Society.

- “Benjamin Franklin: American Diplomacy Traditions.” Harvey Sicherman, January 2007. American Diplomacy: Insight and Analysis from Foreign Affairs Practitioners and Scholars, Beatrice Camp, Editor.

- Farewell Address. George Washington, September 17, 1796. National Archives.

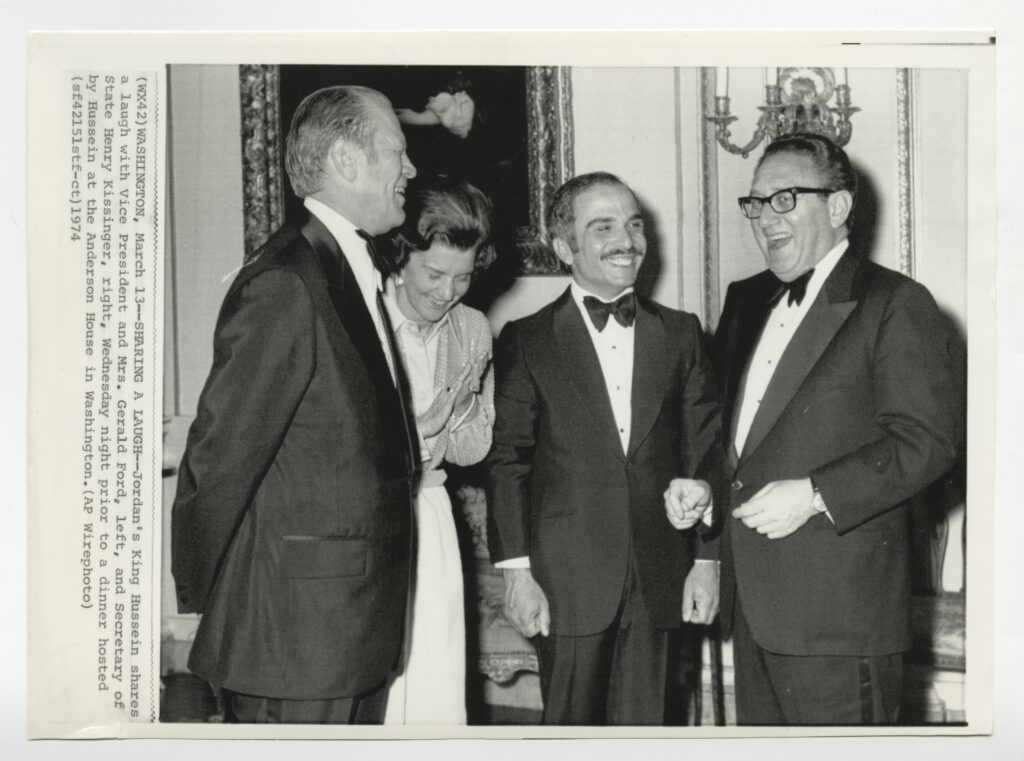

- Benjamin Franklin State Dining Room rug design. Thomas Pheasant, March 1, 2023. U.S. State Department Diplomatic Reception Rooms. (see gallery below)

- Affairs of State: 118 Years of Diplomacy and Entertaining at Anderson House exhibition catalog. The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati.

Background Knowledge

Miriam-Webster notes the first known use of the word diplomacy—defined as “1: the art and practice of conducting negotiations between nations,” and “2: skill in handling affairs without arousing hostility: tact”—in 1766, along with the terms war power, Indian agent, free trade, and colonizer. Famously, 1766 was also the year Dr. Benjamin Franklin appeared in London before the House of Commons, answering 174 questions to help British lawmakers understand the colonists’ resistance to British policies, and to argue for the repeal of the Stamp Act. His four-hour testimony commenting on issues of taxation, representation, and the ability of the colonies to become economically independent from the mother country, made a powerful impression, and was quickly published in London and the American colonies [excerpted here]:

[14] Q. Are not the Colonies, from their circumstances, very able to pay the stamp duty?

A. In my opinion, there is not gold and silver enough in the Colonies to pay the stamp duty for one year…

[36] Q. What was the temper of America towards Great-Britain before the year 1763?

A. The best in the world. They submitted willingly to the government of the Crown, and paid, in all their courts, obedience to acts of parliament. Numerous as the people are in the several old provinces, they cost you nothing in forts, citadels, garrisons or armies, to keep them in subjection. They were governed by this country at the expence only of a little pen, ink and paper. They were led by a thread. They had not only a respect, but an affection, for Great-Britain, for its laws, its customs and manners, and even a fondness for its fashions, that greatly increased the commerce. Natives of Britain were always treated with particular regard; to be an Old England-man was, of itself, a character of some respect, and gave a kind of rank among us.

[37] Q. And what is their temper now?

A. O, very much altered.

[38] Q. Did you ever hear the authority of parliament to make laws for America questioned till lately?

A. The authority of parliament was allowed to be valid in all laws, except such as should lay internal taxes. It was never disputed in laying duties to regulate commerce…

[40] Q. In what light did the people of America use to consider the parliament of Great-Britain?

A. They considered the parliament as the great bulwark and security of their liberties and privileges, and always spoke of it with the utmost respect and veneration. Arbitrary ministers, they thought, might possibly, at times, attempt to oppress them; but they relied on it, that the parliament, on application, would always give redress. They remembered, with gratitude, a strong instance of this, when a bill was brought into parliament, with a clause to make royal instructions laws in the Colonies, which the house of commons would not pass, and it was thrown out.

[41] Q. And have they not still the same respect for parliament?

A. No; it is greatly lessened.

[42] Q. To what causes is that owing?

A. To a concurrence of causes; the restraints lately laid on their trade, by which the bringing of foreign gold and silver into the Colonies was prevented; the prohibition of making paper money among themselves; and then demanding a new and heavy tax by stamps; taking away, at the same time, trials by juries, and refusing to receive and hear their humble petitions.

[43] Q. Don’t you think they would submit to the stamp-act, if it was modified, the obnoxious parts taken out, and the duty reduced to some particulars, of small moment?

A. No; they will never submit to it.

Upon his return to Philadelphia in 1775, Dr. Franklin served as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, who dispatched him on a mission to Canada, then, as the appointed United States minister plenipotentiary, to France in December 1776—with the goal of persuading the French to recognize American independence and join the war against Britain. By 1778, he was successful. When the fighting ended, Minister Franklin remained in France to help write the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Today, Benjamin Franklin is heralded as the “Father of the Foreign Service,” having pioneered the art of American diplomacy that legitimized America as a sovereign nation to be reckoned with on the world’s stage.

In a lecture published in American Diplomacy by Harvey Sicherman, who served as an aide to three U.S. secretaries of state, “four lessons learned from Franklin’s long sojourn in Paris that should be American diplomatic traditions…The first is clarity of purpose…The second…that diplomacy cannot redeem military defeat…Third, in diplomatic technique, there is a difference between a waltz and a march… [and] Fourth…the importance of the gifted amateur.”

The ancient Roman republic, which served as inspiration to Franklin and the revolutionary generation in establishing America’s representative democracy, was known to have developed a distinctive procedure of diplomacy, which embodied the principles that later informed the evolution of America’s diplomatic method, notably: respect for treaties, good faith, equivalence, personal contact, formal meetings and protocol.

In America’s early republic, the selfless civic service and commitment to republican virtue modeled during and after the war by George Washington—America’s version of the classical Roman hero, Cincinnatus—distinguished the United States as a unique peer among the eighteenth-century world’s monarchies and autocracies. During its formative years, however, our country struggled to define its foreign policy, determine how to implement it, and maintain necessary commercial ties with Europe without becoming embroiled in European conflicts and politics. In fact, heated differences of opinion with regard to American foreign policy during the terms of President Washington became the basis for the founding of America’s political parties. In his farewell address to the nation, Washington specifically confronted this divisiveness, promoting a vision of American diplomacy that involved no “entangling alliances” with European powers:

“Observe good faith & justice towds all Nations cultivate peace & harmony with all…permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular Nations and passionate attachments for others should be excluded; and that in place of them just & amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated. The Nation, which indulges towards another an habitual hatred, or an habitual fondness, is in some degree a slave…Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me fellow citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake; since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of Republican Government…The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign Nations is in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop.”

Sequence and Procedure

Ask students, as a class, to share their understanding of the meaning of the word diplomacy.

Share the following quotes with the students, either as a class or in smaller groups, and ask them to use them as a guide in developing a definition for the term diplomacy. Students should record their definitions, and prepare to share them as a class.

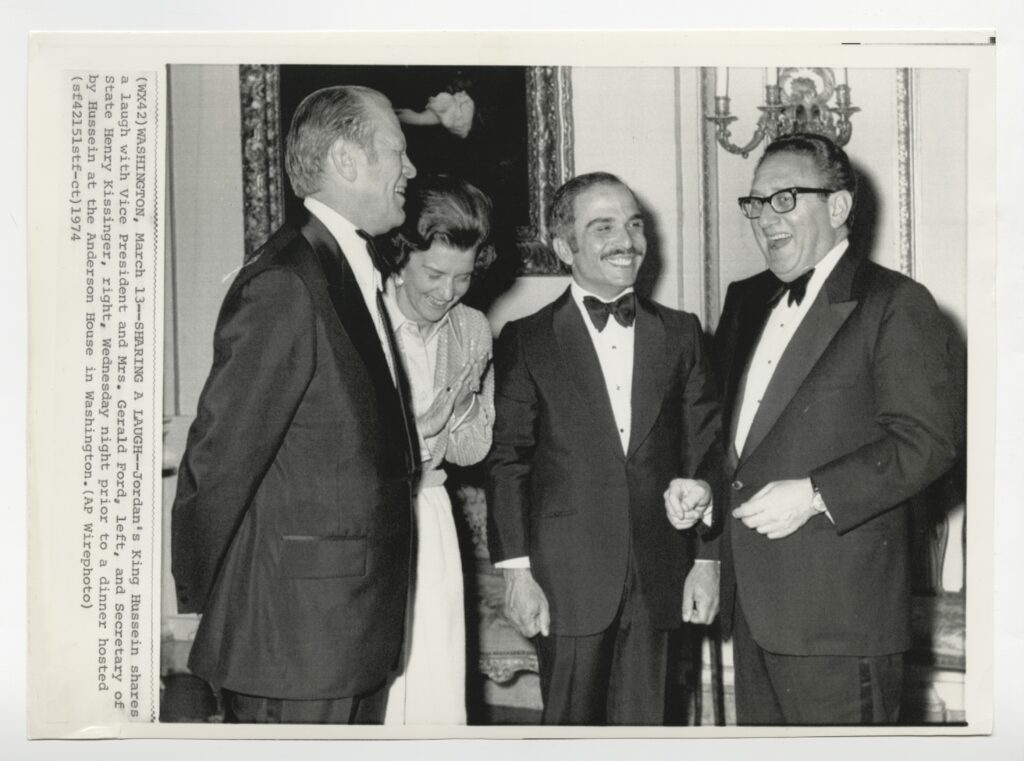

Vice President and Mrs. Gerald R. Ford, King Hussein of Jordan, and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger at Anderson House as featured in “Affairs of State.”

“Diplomacy is listening to what the other guy needs. Preserving your own position, but listening to the other guy. You have to develop relationships with other people so when the tough times come, you can work together.”—Colin Powell, U.S. Secretary of State

“Diplomacy: the art of restraining power.”—Henry Kissinger, U.S. Secretary of State

“Diplomacy is the art of saying ‘Nice doggie’ until you can find a rock.”—Will Rogers, American entertainer

“Beneath all the fanfare, like a steel wire inside a silken thread, runs a kind of life-or-death awareness that foreign policy is made by human beings, with feelings that can be soothed or flattered, bruised or lacerated.”—Wiley T. Buchanan, Jr., U.S. Chief of Protocol

“Of all the cities in the country, Washington is the one where the social life is most important…one dines out continually. This gives people a chance to see each other under the pleasantest circumstances, and affairs of state and international importance may be talked over informally.”—Isabel Anderson, American philanthropist

Compare and contrast the student’s definitions of diplomacy as a class, given the quote or quotes they consulted to develop it.

Share the background information with students, including the dictionary definition and the origins of American diplomacy and Dr. Franklin.

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy visiting Anderson House, from 2023’s “Affairs of State” exhibition.

Introduce students to the categories of essential diplomatic business of the present day—negotiating peace, global security, trade, and human rights; convening summits and multilateral meetings with our international neighbors; hosting official State visits and swearings-in of our nations diplomats; and, celebrating the accomplishments and contributions of global citizens, both foreign and domestic. Discuss how modern American diplomatic business is tempered, using this quotation from President Barack Obama’s 2014 State of the Union Address to spark discussion: “In a world of complex threats, our security and leadership depends on all elements of our power—including strong and principled diplomacy.”

Present an overview of the work published in American Diplomacy by Harvey Sicherman—the “four lessons learned from Franklin’s long sojourn in Paris that should be American diplomatic traditions:”

1. clarity of purpose,

2. the fact that diplomacy cannot redeem military defeat,

3. the difference between a waltz and a march in diplomatic technique, and

4. the importance of the gifted amateur.

Engage in a discussion breaking down each of these four ideas, inviting students to share contemporary or historical examples of causes successfully advanced diplomatically based upon one or more of the aforementioned “lessons” from Franklin.

Direct students to independently research an individual who served a local, state, regional or national cause as a diplomatic ambassador in America. Examples could include individuals officially conducting United States business in foreign diplomacy—like a president, secretary of state or first lady—or an American who informally serves as a cultural ambassador or leader for social change—like a minister, philanthropist, activist, writer, musician or athlete.

Assessment and Demonstration of Student Learning

Students should find between three and five different types of primary source examples as evidence to support the idea that their subject was successful as a minister of their respective cause. Students should compose an analysis of their subject, describing their accomplishments and incorporating the primary source evidence they gathered, being sure to cite which lesson-strategies of Franklin’s their subject employed that contributed to their diplomatic success.

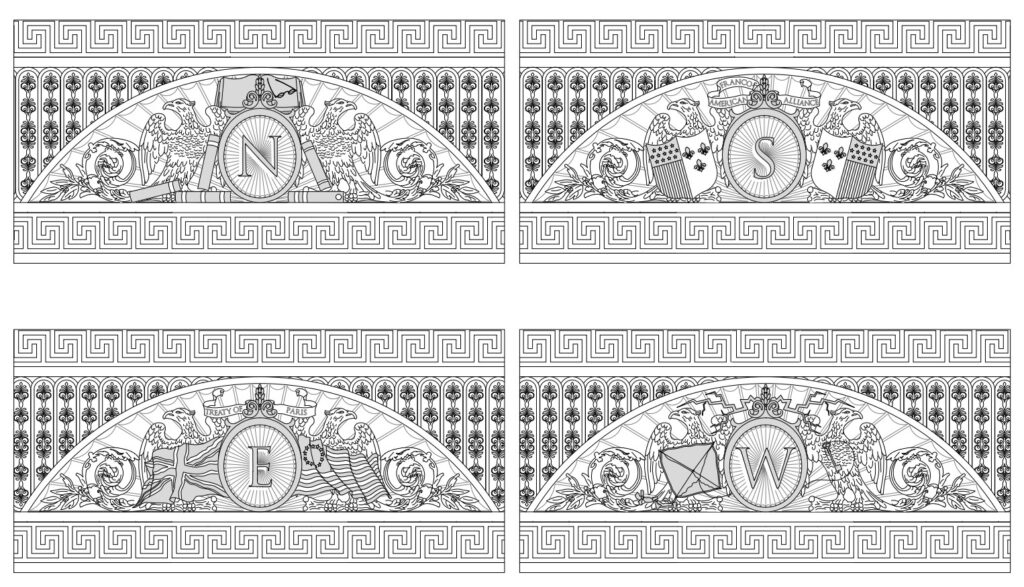

Show students the U.S. Department of State Diplomatic Reception Rooms’ conceptual rug design for the Benjamin Franklin State Dining Room. Each of the cardinal directions are adorned with decorative vignettes that celebrate Dr. Franklin’s diplomatic accomplishments—specifically, the establishment of the Franco-American alliance that resulted in our independence (south) and the signing of the Treaty of Paris with Great Britain (east).

Invite students to design something similar celebrating the accomplishments of the subject of their research.

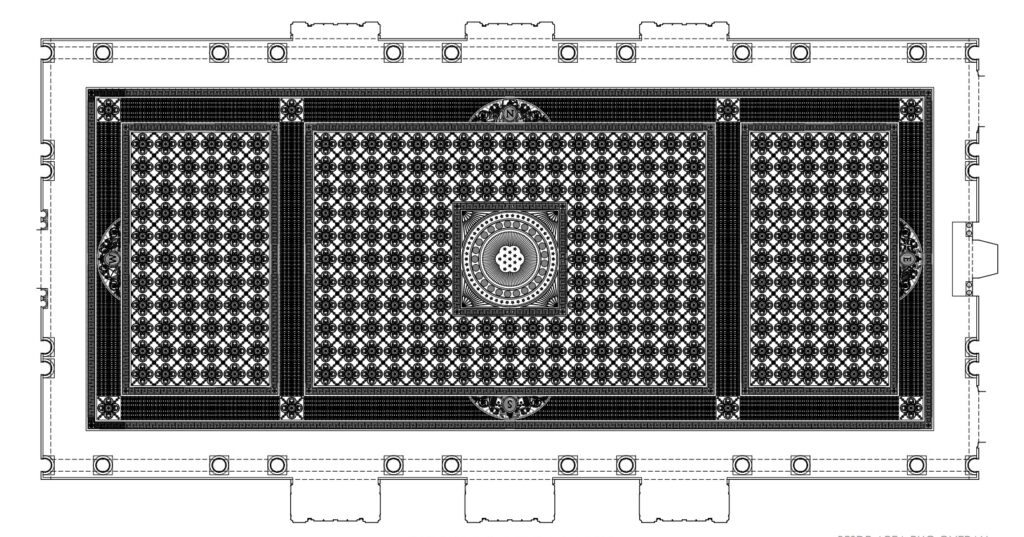

Conceptual rug design for the Benjamin Franklin State Dining Room, with decorative vignettes in each of the room’s cardinal directions that celebrate the achievements of our nation’s first diplomat.

Extension

Ask students to investigate how they might become an ambassador for a cause held dear in their community, envisioning how they might make an impact representing this issue to a larger audience? Students should explain how their commitment follows in the diplomatic tradition of selfless civic service and fulfills their responsibility as a citizen within the American republican tradition.

Revolutionary Achievements Category

Independence, Our Republic

Exploring the Revolution Category

The Revolutionary Republic, The Legacy of the Revolution

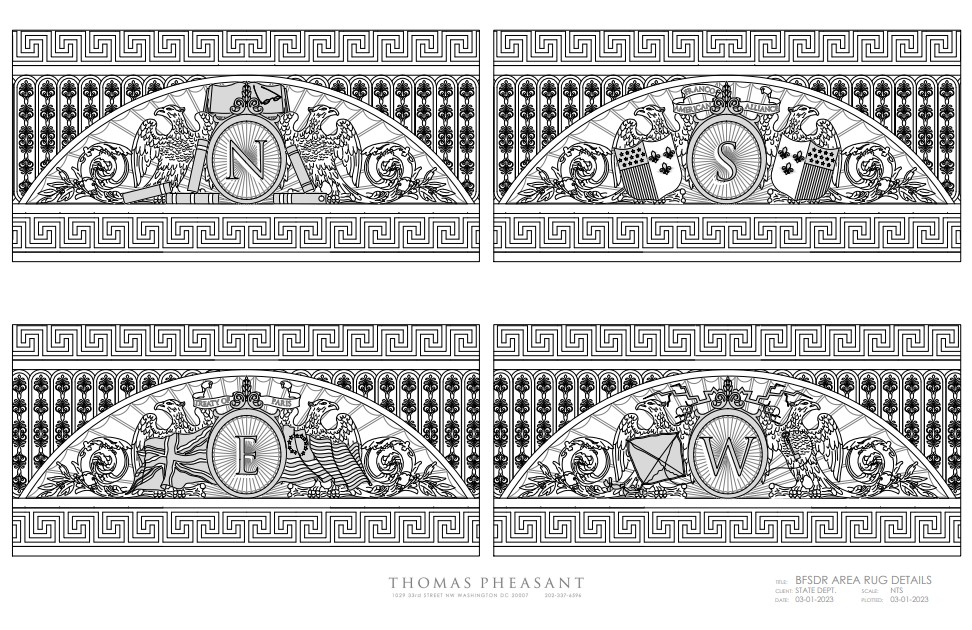

Bisque Figure Group of Louis XVI and Benjamin Franklin

Attributed to Charles-Gabriel Sauvage, Niderviller Factory

ca. 1780-1785The Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State

Psychologically, financially, and militarily, the French alliance was of critical importance to the success of the American Revolution. In 1776 the Continental Congress sent a delegation of three representatives to Paris to secure official French support. Although Silas Deane (1737–1789) and Arthur Lee (1740–1792) were part of the delegation, Benjamin Franklin is the best remembered of the group. He was popular with the French because of his scientific achievements, plain and rustic demeanor, and unpretentious dignity. On February 6, 1778, two treaties between His Most Christian Majesty, the king of France and the fledgling United States were signed. The treaties recognized American independence and sovereignty, pledged mutual defense if Britain tried to interrupt commerce between the two nations, and guaranteed the French possessions in the West Indies. In this bisque group, the inscription “Liberté Des Mers” (freedom of the seas) on the scroll that Louis XVI presents to Franklin refers to these provisions.Although the treaties had been finalized in secret, their signing was known within a few weeks in French and American political circles. To recognize the new alliance formally, Louis XVI received the American commissioners at court in mid-March and there established full diplomatic relations. This figure group may represent the court reception rather than the actual signing in February, although in either case the occasion depicted was certainly auspicious. Symbolically, the power and majesty of France, embodied by the elegant figure of Louis XVI in courtly martial costume, are united with the American cause for independence, represented by Franklin, plainly clothed and gesturing humbly.

Design for Benjamin Franklin State Dining Room Rug

Thomas Pheasant, Interior Designer

March 1, 2023The Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State

The rug's four decorative vignettes in each of the cardinal directions of the room celebrate the accomplishments of our nation's first diplomat and this room's namesake, Benjamin Franklin: North, Franklin's work as a printer and his focus on literacy; South, the establishment of the Franco-American alliance that resulted in our independence; West, his electrical experiments; East, the signing of the Treaty of Paris.

Design for Benjamin Franklin State Dining Room Rug

Thomas Pheasant, Interior Designer

March 1, 2023The Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State

Reinforcing the theme of our sprawling nation, the rug will indicate each of the cardinal directions, accurately oriented on its four sides.