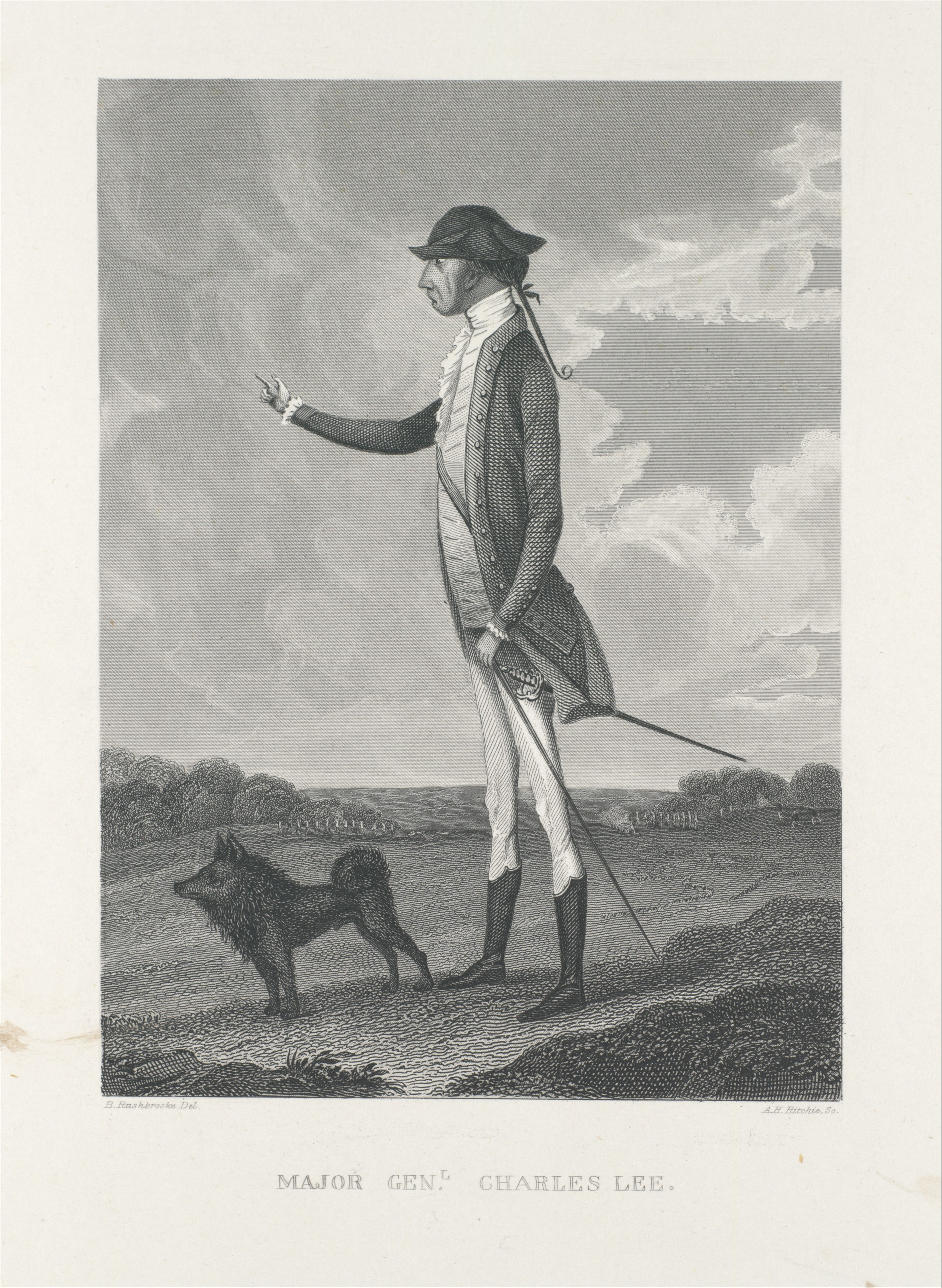

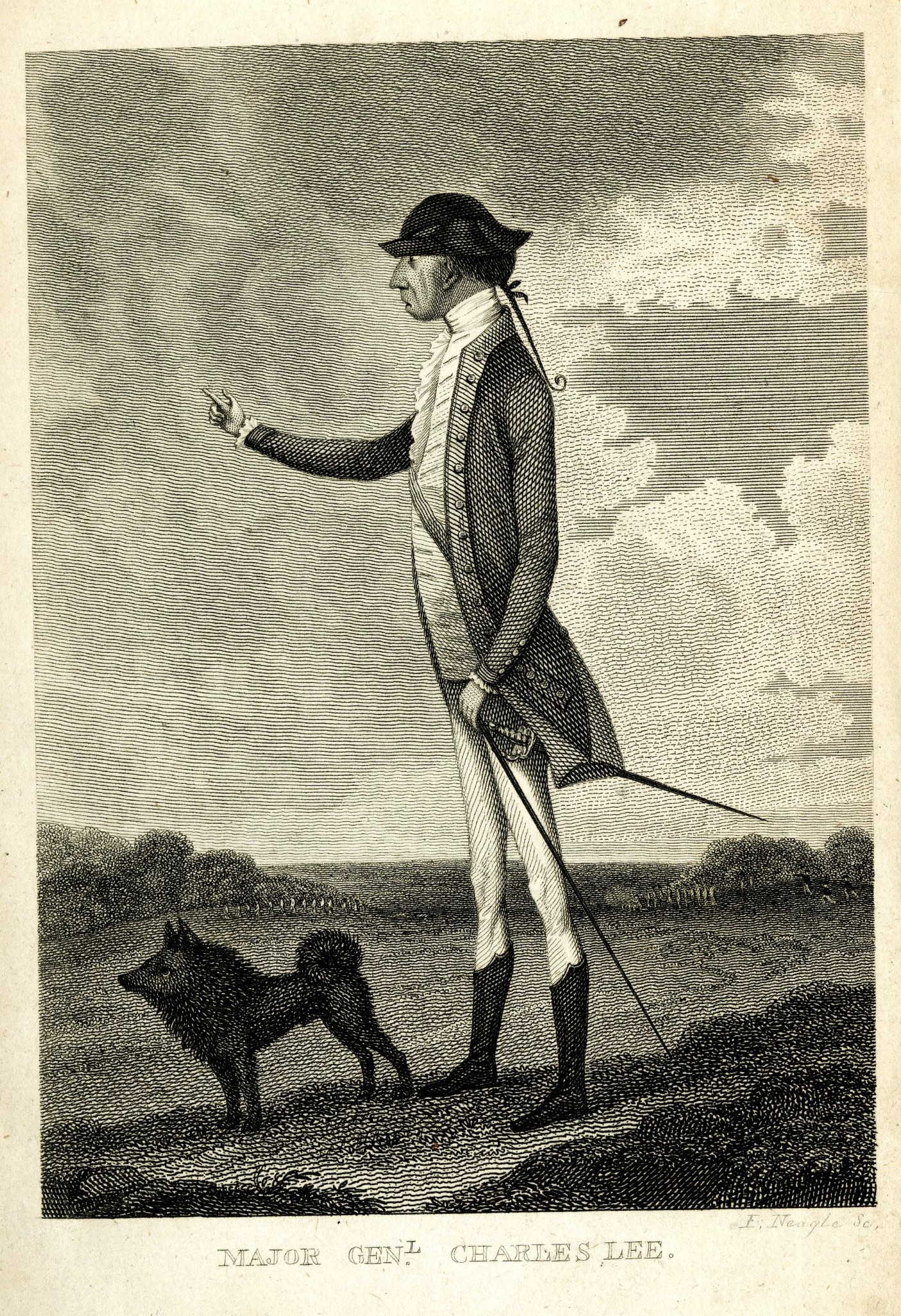

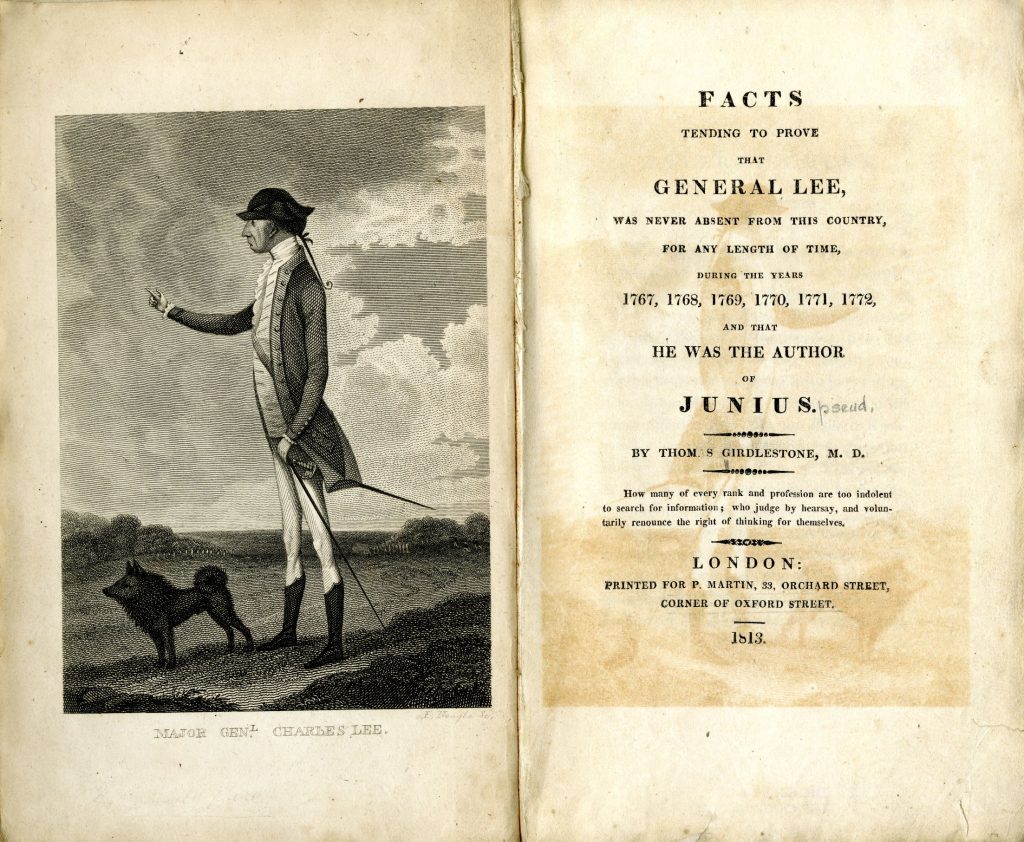

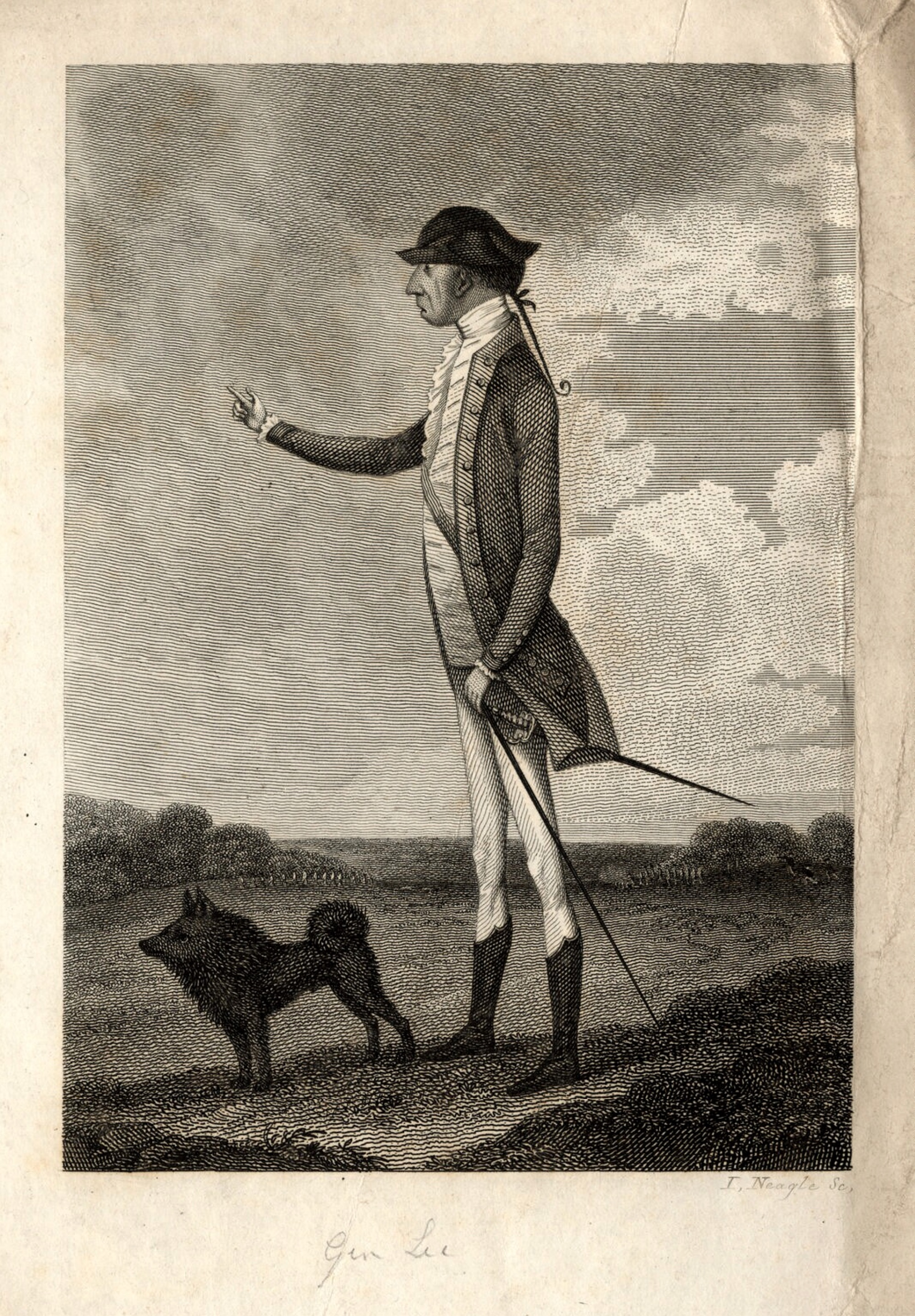

This engraving is probably the most authentic surviving likeness of Charles Lee. It is based on a drawing of Lee by Barham Rushbrooke (d. 1782) of West Stowe, Suffolk, a village north of Bury St. Edmunds. An attorney, Rushbrooke painted portraits and portrait miniatures, chiefly of Suffolk gentry. The original of his drawing of Lee does not seem to survive. It is known only from this print, which was engraved by James Neagle as the frontispiece of a book by Thomas Girdlestone (1758-1822) entitled Facts Tending to Prove that General Lee, was Never Absent from this Country, for any Length of Time, During the Years 1767, 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772, and that he was the Author of Junius (London: Printed for P. Martin, 1813), and from a copy of the Neagle engraving made by American engraver Alexander H. Ritchie and published in 1860.

A physician, Girdlestone was convinced that Lee was the author of the “Letters of Junius,” a series of pseudonymous essays highly critical of the British government published in London newspapers beginning on January 21, 1769, and concluding on January 21, 1772. The identity of Junius has never been determined. Girdlestone argued that Lee’s handwriting matched that of a letter written by “Junius,” that the composition of the Letters of Junius was consistent with Lee’s literary style, and that Lee was in Britain when the letters were published and devoted much of his time during those years to writing.

Girdlestone obtained the Barham Rushbrooke portrait of Lee for his book, probably from the Davers family of Rushbrooke Hall, Suffolk, or from the artist’s grandson, Robert Rushbrooke, who was married to a daughter of Sir Charles Davers, 6th Baronet Davers of Rougham. Sir Charles Davers had attended the grammar school in Bury St. Edmunds with Charles Lee and the two had become close friends. Lee was often at Rushbrooke Hall until he left for America in 1773. According to Girdlestone, “General Lee’s likeness was taken on his return from Poland, in his uniform as aid-de-camp to Stanislaus king of Poland. But though it was designed as a caricature, it is allowed, by all who knew General Lee, to be the only successful delineation of his countenance or person.” Girdlestone also noted that “General Lee was a remarkably thin man” (Facts Tending to Prove, pp. iii-iv, 4).

Girdlestone obtained the Barham Rushbrooke portrait of Lee for his book, probably from the Davers family of Rushbrooke Hall, Suffolk, or from the artist’s grandson, Robert Rushbrooke, who was married to a daughter of Sir Charles Davers, 6th Baronet Davers of Rougham. Sir Charles Davers had attended the grammar school in Bury St. Edmunds with Charles Lee and the two had become close friends. Lee was often at Rushbrooke Hall until he left for America in 1773. According to Girdlestone, “General Lee’s likeness was taken on his return from Poland, in his uniform as aid-de-camp to Stanislaus king of Poland. But though it was designed as a caricature, it is allowed, by all who knew General Lee, to be the only successful delineation of his countenance or person.” Girdlestone also noted that “General Lee was a remarkably thin man” (Facts Tending to Prove, pp. iii-iv, 4).

The figure in Rushbrooke’s portraits is tall, thin and has a large nose. These might be dismissed as caricature, were they not echoed by Sir Henry Bunbury, the son of Lee’s first cousin, who published an account of Lee from his family papers in the early nineteenth century. The memoir, which may have been written by Bunbury’s father, described Lee as having “a restless mind, and a hot and imperious temper. Eager, disputatious, acute, jealous of honour, brave to an excess, and possessing talents far above the common order, he appeared a man likely to hew for himself a path of glory, or to perish prematurely in a duel. In person he was tall and extremely thin; his face ugly, with an aquiline nose of enormous proportion; his manners were high bred and impressive, though he was singular, and in his latter days slovenly, in his habits. He was a fast friend, but a bitter enemy” [“Memoir of Charles Lee,” in Henry Bunbury, ed., The Correspondence of Sir Thomas Hanmer . . . with A Memoir of his Life. To Which Are Added Other Relicks of a Gentleman’s Family (London: Edward Moxon, 1838), pp. 453-54].

The Rushbrooke portrait appears, at first look, to depict a gentleman in military uniform strolling with his dog in the countryside, but on closer examination two lines of soldiers can be discerned in the background, suggesting that this is a portrait of Lee and his favorite dog on a European battlefield. Lee brought such a dog—a Pomeranian named Spada—with him to America, along with several other dogs, and lavished attention on them. John Adams wrote to James Warren about Lee on July 24, 1775: “He is a queer Creature—But you must love his Dogs if you love him, and forgive a Thousand Whims for the Sake of the Soldier and the Scholar.” The letter was intercepted by the British, who published it to embarrass Adams. Lee wrote to reassure him on October 5, 1775: “As you may possibly harbour some suspicions that a certain passage in your intercepted letters have made some disagreeable impressions on my mind I think it necessary to assure You that it is quite the reverse. Untill the bulk of Mankind is much alter’d I consider the reputation of being whimsical and eccentric rather as a panegyric than sarcasm and my love of Dogs passes with me as a still higher complement. I have thank heavens a heart susceptible of freindship and affection. I must have some object to embrace. Consequently when once I can be convincd that Men are as worthy objects as Dogs I shall transfer my benevolence, and become as staunch a Philanthropist as the canting Addison affected to be.” Lee added a postscript: “Spada sends his love to you and declares in very intellegible language that He has far’d much better since your allusion to him for He is carress’d now by all ranks sexes and Ages.” After the Siege of Boston ended, Spada accompanied Lee south. Congressman Samuel Johnston wrote to his sister Hannah on May 31, 1776, that Lee had passed through Halifax, North Carolina, where it was said that “the general will not suffer Spado to eat bacon for breakfast (a practice very general both with gentlemen and ladies in this part of the country) lest it should make him stupid.”

The dog in the Rushbrooke portrait is probably Spada, who was apparently separated from his master about the time Lee was taken prisoner in New Jersey in December 1776. Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, published in Baltimore, included an advertisement on February 11, 1777, offering a twenty dollar reward for his return: “LOST or STOLEN, a very remarkable black shaggy dog of the Pomerania breed, called SPADO. He belongs to our brave but unfortunate GENERAL LEE, and was seen in the possession of a person who called himself JOSEPH BLOCK, at Wright’s Ferry, on Susquehanna, about the 25th of December last. It is supposed that BLOCK who pretended to have undertaken to carry him to Berkeley county, Virginia, has parted with him for a trifling consideration, or lost him on the road. Whoever gives information where the said dog may be had, or will bring him to the persons hereafter named, shall on the dog’s being produced, receive the above reward and no questions asked. Robert Morris, Esq; Philadelphia; Jo. Nourse, at the War-Office in Baltimore; or James Nourse, Berkeley county, Virginia.” Spada was apparently never found.

The Neagle engraving of the Rushbrooke portrait in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery in London (above) is apparently a proof. Copies of the engraving from Grimblestone’s book include the legend “Major Genl. Charles Lee” along with Neagle’s name, but do not identify Rushbrooke as the original artist. “Major Genl. Charles Lee” was used as the title by Alexander Hay Ritchie (1822-1895), who copied the engraving (below, from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art) for use as an illustration in George Henry Moore, The Treason of Charles Lee (New York: Charles Scribner, 1860), where it appears following page eighteen. Ritchie identified himself as the engraver and, at lower left, properly attributed the original work to “B. Rushbrooke.”