How will we understand the American Revolution in the future we are making?

For more than two hundred years the American Revolution defined our nation and the ideals to which it is dedicated. For most of that time the heroes of the American Revolution were the cherished heroes of our nation. But in the last generation many Americans have turned away, suspecting at first and then in greater numbers believing that the Revolutionaries do not embody ideals we cherish, touching off a debate about the nature and meaning of our Revolution that will go far in shaping our national identity and the ideals that shape our conduct. Much more is at stake in this debate than the fate of monuments and memorials.

On the one hand are those—their voices have been particularly loud in the last year—who argue that the Revolutionaries did not go far enough or fast enough to fulfill the ideal of equality. Some go much further and argue that the Revolutionaries did not believe in equality, and simply used the rhetoric of universal natural rights to justify a political movement intended to impose deeper and more lasting forms of inequality.

On the other hand are those who insist that the Revolutionaries created a remarkable political and constitutional order which has facilitated the development of a free, wealthy and powerful nation which has, through gradual and at times dramatic moments of reform, provided for equality before the law and equality of opportunity for its citizens. While acknowledging that the men they admiringly refer to as the Founding Fathers were imperfect, they insist that we judge them in “the context of their time”—a time in which inequalities were commonplace. Their opponents are equally determined to stand in judgement of those same Founders, finding them wholly unworthy of admiration because they did not live according to standards of our time.

Although they have little in common otherwise, people on both extremes look on the Revolution as a political, legal and constitutional event, and pay little attention to the Revolution as a social and cultural one. As a consequence people on both sides, and many in between, misunderstand the American Revolution.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

To understand our Revolution, there are few better places to begin than with the view of John Adams, a thoughtful revolutionary if ever there was one, who lived long enough to have historical perspective on the events through which he had lived and in which he played such a prominent role. For Adams, the American Revolution began at the end of the French and Indian War, when the British began asserting themselves as never before in colonial affairs, and extended through the Declaration of Independence. Adams regarded the Revolution as a change in the sentiments of the American people, involving alienation from the British monarchy and the adoption of republican ideas about government, which he said had occurred before the war began. This was, for Adams, the real American Revolution.

Although it’s far from the way most modern Americans understand the Revolution, this view has some merit. The rejection of monarchy in favor of an experiment in self-government made the American Revolution an extraordinary event. In 1776 nearly everyone on Earth was the subject of a monarch. True self-government existed only in the theoretical speculations of philosophers and the conversations of coffeehouse radicals.

Few of us, however, share Adams’ view that the American Revolution was almost over before the war began. This is, at least in part, because our generation doesn’t readily grasp how radical the rejection of monarchy was in 1776. We live in a world in which most governments are, at least nominally, republican—including governments, like that of the People’s Republic of China, that share few of the characteristics we associate with republics, and governments of constitutional monarchies, like that of Great Britain, that are republican in practice.

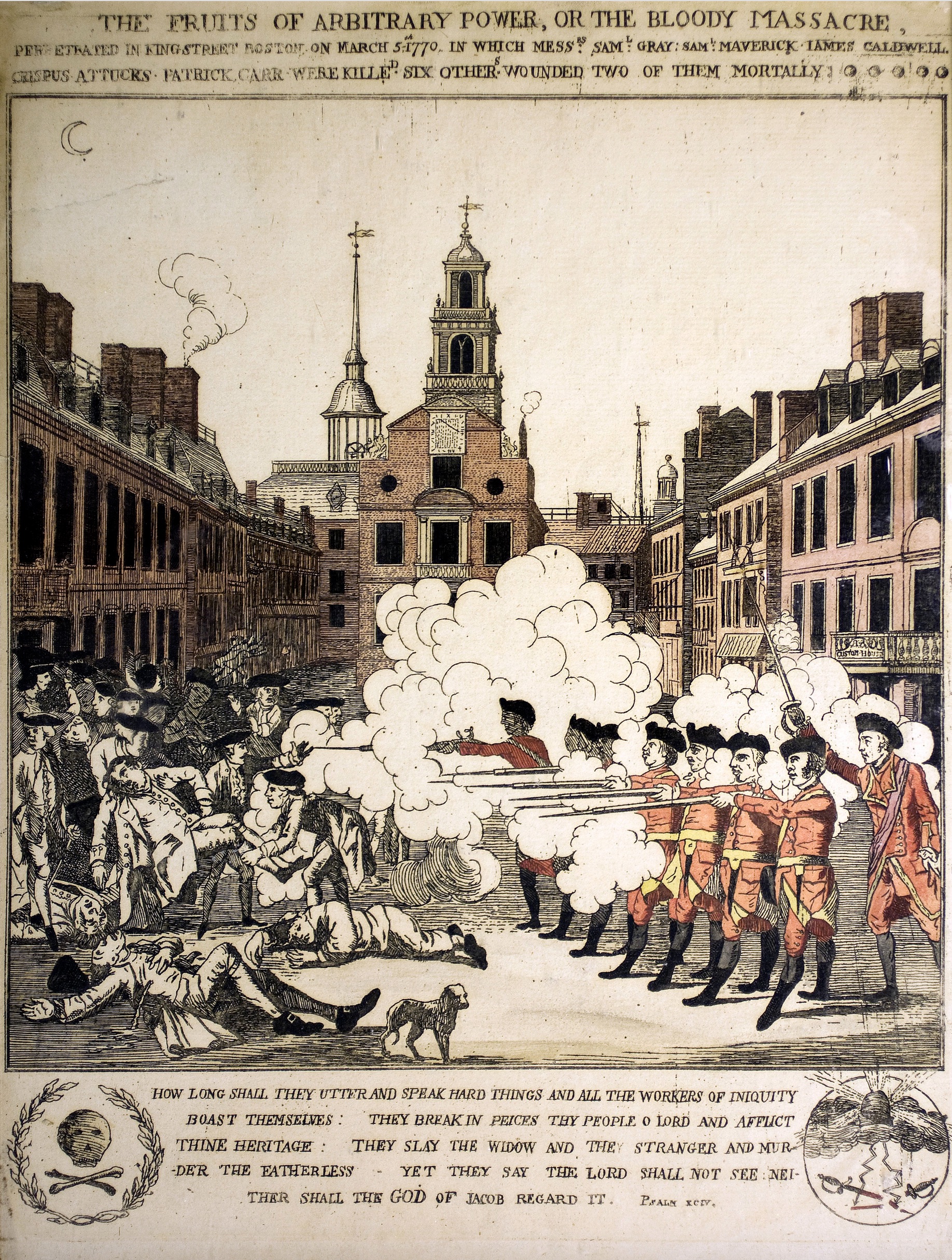

The success of our Revolution and the republic we created encouraged the world to follow our example. Much of the world did, and now what we accomplished no longer seems particularly radical. In this sense, the American Revolution succeeded beyond the expectations of its most enthusiastic supporters—except that, as we all know, many of the self-described republics of modern times are in fact some of history’s most vicious and sordid tyrannies. The idea that humankind should be governed by republic principles has triumphed, but the reality remains much as it was when Rousseau challenged the world: mankind was made to be free, but is everywhere in chains. If understanding the fundamental ideals of our Revolution ever mattered, it matters now, when tyrants stalk the world falsely claiming to represent sovereign people—people they routinely oppress and brutalize.

John Adams was right that the American commitment to self-government was at the heart of our Revolution. He simply underestimated the revolutionary consequences of the war in making it so. For him it was the war that followed the Revolution. In fact, the war was an intrinsic part of the Revolution.

This has been less and less appreciated, in the popular mind, in recent decades. The Revolutionary War now occupies little time in our history classrooms, where the focus is on political and constitutional events—chiefly the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the Federal Constitution—and the statesmen who shaped them. The Revolutionary War is dealt with in a few broad strokes. It seems small to many Americans, at least when compared to later wars. Its battles seem like mere skirmishes, its death toll paltry, its suffering minor, its sacrifices modest.

We are easily deceived by the war’s scale. It was, in fact, until the interminable, undeclared foreign wars of modern times, the longest war in American history. It touched every part of the new nation, from Maine to Florida, and westward to the Mississippi. It touched every community and brought sorrow and loss to many thousands of families. In proportion to the population, it took the lives of more Americans than any other war in our history except the Civil War. The Revolutionary War was itself a civil war that degenerated into a brutal partisan conflict between loyalists and patriots. It was a traumatic event punctuated by episodes of extraordinary courage and of remarkable brutality.

The war mobilized an extraordinary number of Americans—as soldiers, of course, but many more as laborers, sailors and craftsmen. It had a dramatic effect on the lives of women—many of whom lost husbands, sons, brothers and fathers, many more who were forced to manage for themselves and do work that they would never have had to do in peacetime, and some of whom followed the army on the march, in camp, and a few even to the battlefield. It also had an enormous effect on the lives of the enslaved. Many of them took advantage of the war to free themselves—running away, serving in or with the army as soldiers, laborers or servants, bringing suit for their freedom, and taking advantage of the first statutes abolishing slavery ever adopted in the history of the world.

Little of this would have happened if the Revolutionary War had been brief—if, as many patriots hoped, the war had ended when the British evacuated Boston in the spring of 1776. But that didn’t happen. When George Washington took command of the Continental Army in June 1775 he had implied to his wife, Martha, that he would be home by Christmas. That was undoubtedly wishful thinking, but he never imagined that eight Christmases would come and go before he returned to Mount Vernon.

A war of that scale, fought in every part of the country, over such an extended period of time, was bound to transform people’s lives. To understand how deeply it effected people’s lives we have only to read some of the thousands of pension declarations veterans made fifty years and more after the war ended. For most of them, the war had been the singular event in their lives, never to be forgotten. Many bore physical scars from the war and for many more, the war was an upheaval that lifted their lives out of the course it would otherwise have followed and set them on an entirely new path. We will never understand the Revolution until we understand it in these terms.

The pension file of Jesse Stout, a New Jersey farmer, tells us that he served for most of the war. He was shot through the shoulder in 1777 and after recuperating, he returned to service. When the war was over he moved to Pennsylvania, then back to New Jersey, then in 1795 to Ohio, then seven years in Indiana, before settling finally in west central Illinois. Such an odyssey would have been unimaginable before the Revolution. But it was far from unusual. Thousands of Revolutionary War veterans moved west or south or north after the war—the population seemed at times to be charged with a restless energy. When the American Revolution began, the colonists nearly all lived within two hundred miles of the ocean, and most lived within fifty, as earlier generations had done.

The Revolution changed that forever. The graves of the men and women of the American Revolution are scattered over nearly half of the continent, and are found as far away as Missouri and Illinois. John Abstom of Pittsylvania County, Virginia, fought at Kings Mountain when he was nineteen, moved to Kentucky after the war, and settled finally in Texas. Charles Polk of Mecklenburg County was a teenager when he served in the defense of Fort Moultrie in 1776. He survived the war, married and settled in Tennessee, before he moved to Texas. Stephen Taylor served for three years in the Massachusetts Continental Line, moved around upstate New York, and lived for the last years of his life in the Minnesota Territory, a region barely mapped when the Revolutionary War began.

The war was a defining experience for those who never strayed far from the home. Marmaduke Maples enlisted in the North Carolina Continental Line in January 1777 and later signed up to serve for the duration of the war. He fought with Washington’s army at Brandywine, Germantown and Monmouth and was captured when Charleston capitulated in June 1780. He was imprisoned for some two years, much of it on a prison hulk moored in the harbor, where the suffering prefigured Andersonville, except the prisoners packed in the hulks starved within sight of a city where food was abundant, their miserable lives punctuated by the daily ritual, in summer’s heat and winter’s cold, of burying their dead comrades in shallow graves scooped from the mud near the ship.

Most of the men Maples served with died on the prison hulks or agreed to enlist with the British as their only means of escape. Maples refused to join the British army. Malnourished and sick, he survived until he was exchanged in 1782, when he was loaded on a British transport and dumped at Jamestown, Virginia. Maples and the remaining North Carolinians marched to Hillsborough where they were captured by raiding loyalists in September 1782. Maples was so close to death that the loyalists paroled him. He was still on parole in early 1783, when he mustered at Cross Creek (now Fayetteville), expecting to rejoin the army.

At several points in this odyssey Maples could have escaped the army, but he kept returning to service, and it seems unlikely that he did so simply to obtain bounties that went constantly unpaid. The inescapable conclusion is that he was committed to the cause. After the war he went home to Lincoln County, where he taught school. He lived for another sixty years, and when he was too old and broken down to support himself any longer and applied for a veterans pension, his neighbors testified that it was well known that he had been soldier of the Revolution and shared in many of its greatest battles.

The remarkable thing about his story is how unremarkable it was. The story of David Dorrance, a Connecticut captain, is much the same. He joined the army right after Bunker Hill, fought in its great battles, and was shot through the right hip by Tories while leading a raid in Westchester County, New York, in 1781. It took him more than a year to recover, but he, too, returned to the army, despite being disabled. He carried the musket ball for decades, and in the last years of his life he could barely walk.

The early republic was filled with men with stories like these. “At the close of that struggle,” Abraham Lincoln wrote, “nearly every adult male had been a participator in … its scenes. The consequence was, that of those scenes, in the form of a husband, a father, a son or brother, a living history was to be found in every family—a history bearing the indubitable testimonies of its own authenticity, in the limbs mangled, in the scars of wounds received, in the midst of the very scenes related—a history, too, that could be read and understood alike by all, the wise and the ignorant, the learned and the unlearned.” At Gettysburg, when Lincoln referred to “our fathers,” who “brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation,” he meant the ordinary men—the fathers of his own generation—who had won the war.

The war made the American Revolution a people’s revolution. We don’t see that as clearly as we should, and in the future we must. We have a tendency to think of our Revolution as an event dominated and driven by a group of people we call the Founding Fathers or sometimes even more simply, the Founders. This is a group of men, all of them white and most of them wealthy, who were most active in the creative state building of the Revolution. They were mostly very conscious that they were participating in one of the great moments in world history and many cultivated reputations for unselfish public service. Some of them—Washington, Franklin, Jefferson and John Adams most clearly—recognized that they were historic figures and saved their papers for us to read. They wanted us to remember them, and we do.

We don’t see the other Revolutionaries—the ordinary men and women for whom the Revolution became a transcendent and transforming cause—as clearly. Their Revolution was one of the defining events of modernity but it was over a few decades before the invention of photography—one of the defining technical achievements of modern times—which makes it possible for us to see the faces of the ordinary people who fought our Civil War, who protested for women’s rights, who suffered in the mines and the slums, who labored in the mills and who bore the scars of slavery. We can see their faces and easily imagine them as men and women like us.

Nor did the ordinary men and women of the Revolution leave us a large body of personal writings to make up for this deficiency. They weren’t Romantics. They didn’t spend a great deal of time thinking about themselves. They wrote some about their experiences but rarely about themselves—occasionally they share ideas but not often their feelings. Their diaries are too often spare and unrevealing. Their personal letters are not much better.

Just occasionally we get a glimpse of their emotional lives through the veil of reserve that they maintained. Acquilla Cleaveland was a young private in a New Hampshire ranger company when he wrote to his wife, Mercy, on June 10, 1777. His company had been patrolling the west shore of Lake Champlain for sixty miles north of Fort Ticonderoga, but had seen only one Indian scouting party. They had no reports of British movements to the north. “By what we herd they will not trouble us here this summer.” He had no idea that a British army was descending on them. He was more worried about smallpox, which he said loyalists were trying to spread to American troops. Food was expensive, he wrote, and promised recruitment bounties remained unpaid—all in the workaday prose of an ordinary soldier. Then he closed:

My Dear wife after my regards to you, I don’t know when I shall see you, but would have you do as well as you can. Remember that God is as able to support you now as ever, if you trust in Him. I shall come home as soon as I can get a chance. And so I remain your loving husband till Death.

A week later, on June 17, Acquila Cleaveland was killed by a party of Mohawks sent south by the British in advance of Burgoyne’s army.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Why did they do it? Why did they risk their lives, and give their lives, in the American Revolution? These are essential questions, and one of the basic flaws of the present, overheated public dialogue about the Revolution, is that the participants aren’t asking them.

At the level we need to be asking these questions, the documents often fail to give us clear answers, but the record is far from silent. Margaret Corbin was young and recently married when the war began. She lived in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, in the wooded hills west of Gettysburg, though that town was not founded until she was ten and its terrible moment was near a century away. When Margaret was small a party of Indians killed her father and carried off her mother, who was never to be heard from again. At twenty-one Margaret married a local farmer, John Corbin, and when the war began he enlisted in the First Company of Pennsylvania Artillery.

Men like John Corbin did not read treatises on natural rights or political economy like John Adams or Thomas Jefferson did. Women like Margaret Corbin certainly did not. Few of them had ever heard of John Locke or Baron Montesquieu or ancients like Cicero. Taxes on paint, paper, lead, tea and glass—the Townshend Duties that so angered colonial merchants—didn’t touch people like John and Margaret Corbin, who didn’t buy paint or drink tea, who didn’t use much paper, and for whom lead was something cast into musket balls rather than used to hold window glass in place.

Men and women who lived in the colonial backcountry valued their independence. They had little property. In the Corbins’ Pennsylvania, where the law was more generous to squatters than elsewhere, many lived on land to which they had no clear title. What little they had—a bedstead, a few pots, a gun—belonged to them, and there was no squire to whom they owed obedience or to whom they paid rent. And if they liked they could go, joining the constant movement southward through the valley, or press westward, toward the Appalachia frontier, where the British had drawn a line forbidding settlement—a symbol of their intention, or so it seemed to Americans across the colonies and up and down the social scale, to impose much tighter control on their restless, unruly subjects.

These were people to whom independence was not a philosophical abstraction. It was a personal cause, and when they spoke of independence they meant personal independence as much or more than they meant national independence.

When John Corbin went off to war Margaret went with him and supported herself doing laundry, mending clothes, cooking, and nursing the sick. George Washington didn’t like the practice, but grudgingly accepted it, and at nearly every moment of the war, women were present. On November 16, 1776, John Corbin’s battery was stationed on a ridge on the northern end of Manhattan, which the British and Hessians had to take before approaching Fort Washington—the last American stronghold on the island. When John Corbin was killed Margaret was nearby and took his place on the gun crew. She fell hideously wounded as the battery was overrun, hit in her left shoulder and arm, jaw and left breast. She was captured, though in so much pain, if she was conscious, that she can hardly have cared about falling into the hands of the enemy. Released, she was taken by wagon to Philadelphia, where she languished for months.

Margaret’s story reminds us—and we clearly need reminding these days—of the extraordinary lengths to which the men and women of the revolutionary generation went to establish their independence. Perhaps if we had her photograph we would not be so quick to abandon the memory of her generation, but we don’t. Forgetting, Americans turned her sacrifice and that of other women like her into the genteel fantasy of Molly Pitcher, which our generation—so certain of its sophistication, so cynical—dismisses as a myth. If we had her photograph we would know her as a disfigured and scarred young woman who lived on, permanently disabled, drawing rations at West Point for the rest of her life, finally buried when she died at forty-eight in a grave that has been lost to memory. She paid the cost of liberty, and in doing so lost the personal independence she was probably fighting to maintain, or secure for herself, her husband, and for the family she never had.

We can, and often do, tie ourselves in knots trying to understand the original intent of the Revolutionaries who drafted our first constitutions and the laws under which we live. There are indeed many insights to be gleaned from the reflections of John Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton and Jay, who all left their papers for us to read. But at its most fundamental, the American Revolution was a struggle for self-government—to vindicate the right of ordinary people to manage their own affairs—and the theoretical speculations of the most sophisticated founders tells us little that we cannot learn from the simple explanation of Capt. Levi Preston of Danvers, Massachusetts, who explained decades after the war that “what we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we always had governed ourselves and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.”

This same intent—independence defined as autonomy, self-government as a people and as individuals—is woven through the words and deeds of innumerable ordinary people who lived through our Revolution. Among them was Jeffrey Brace—a native of Mali, enslaved as a teenager, beaten and abused by a succession of masters in the Caribbean and later in Connecticut, who enlisted in the Continental Army with a promise of freedom at the end of his service. When he was finally discharged in the summer of 1783, he was awarded the Badge of Merit. “Thus was I,” he remembered, “a slave, for five years fighting for liberty.” We can know his story because almost thirty years after the war he told it to a young lawyer who wrote it all down. Like so many others, he had fought for personal independence. “The first time I made a bargain as a freeman for labor” after the war was one of the most memorable days of his life. “I enjoyed the pleasures of a freeman; my food was sweet, my labor pleasure: and one bright gleam of life seemed to shine upon me.”

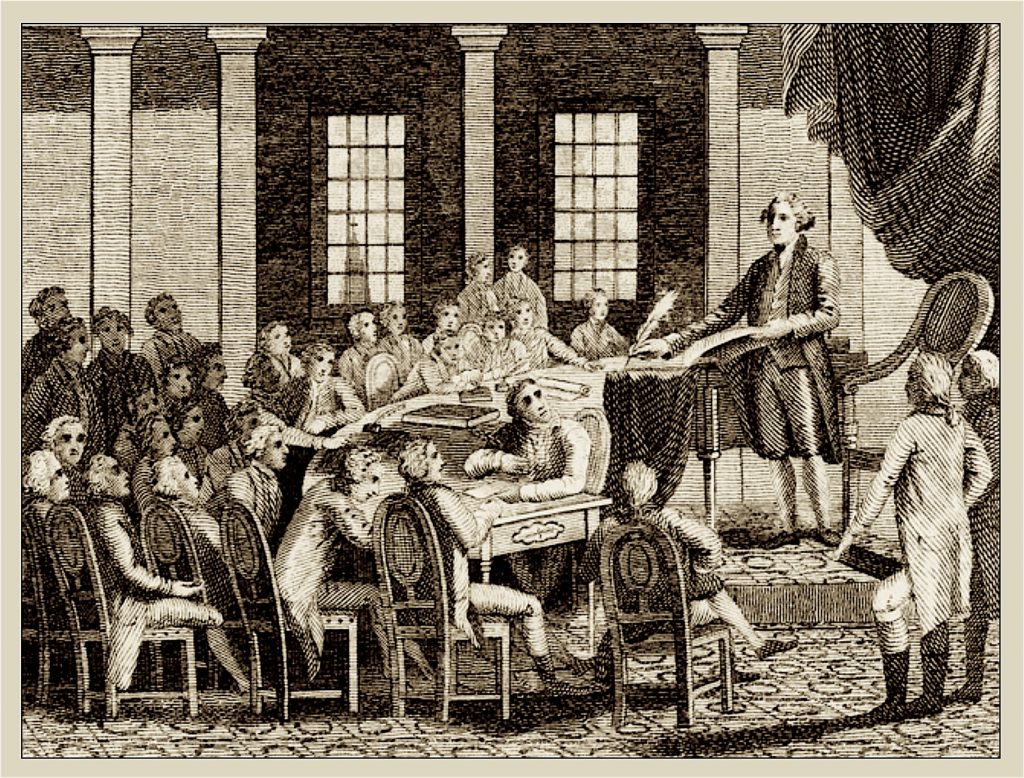

The achievements of the American Revolution were not the achievements of a small group of men we call the Founding Fathers. They were thinkers and leaders, creative statesmen to be sure, but the achievements of the American Revolution are the common achievements of thousands of people. The leaders we remember most clearly played essential roles, but often that role was to articulate, in declarations, constitutions, bills of rights, laws, learned essays and popular polemics, ideas that were being expressed in varying ways and to various degrees of precision, by thousands of people.

Leaders have to lead, and the essence of leadership is a balance between fulfilling the ideas and expectations of the people led and expressing new ideas and translating those ideas into action. The first is critical, because the hope of seeing their ideas and expectations fulfilled is the reason people embrace leaders, and a leader without followers is just someone taking a walk. Philosophers had been talking about natural rights and what we have come to call civil rights for more than a century when the Revolutionary War began. Political thinkers had concluded, in weighty books circulated among themselves, that a republic was, in theory at least, the best sort of government. Thomas Jefferson didn’t vindicate our natural rights. James Madison and Alexander Hamilton didn’t give us our republic.

They were taken for us by Charles Polk and Acquilla Cleaveland, and by Margaret Corbin and Jeffrey Brace. They were taken for us by the officers and men of the Continental Army, who scorned a military takeover at the end of the war. They were taken for us by thousands of ordinary Americans who became our first veterans, who went home at the end of eight years unpaid, with promises made to them by the government unfulfilled, mostly penniless, many in rags, but conscious of duty faithfully performed in a war of liberation that had made possible, for the first time, governments based on the principle of popular sovereignty and limited by devotion to the rule of law and limited, by constitutional principle, to prevent governments from invading the legitimate rights of the people.

Thomas Paine had told them to expect independence to come at a high price. “What we obtain too cheap,” Paine wrote in Common Sense, “we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as freedom should not be highly rated.”

Independence—the accomplishment of eight years of desperate war, the shared accomplishment of thousands of ordinary Americans—made possible all that we have become. Independence led, despite the misgivings of the Founding Fathers about democracy, to the development of a liberal democracy in which ordinary people participated to a degree the Founders never imagined or foresaw—the people’s revolution, you see, confounded their expectations—and left us with a government republican in form but popular in practice, with constitutional boundaries preventing the popular will from invading individual rights—the very individual autonomy so many of the Revolutionaries had fought to achieve.

The war created a nation where none had existed before—a nation based, not on ethnicity, religion or ancient traditions, but on shared principles and shared history—a shared history that involved heroic leaders like Washington but also heroes fit for a democratic republic like Sergeant Jasper and Peter Francisco, along with eighteenth-century gentry like Francis Marion and Benjamin Franklin, made over into everyman heroes. The war gave us the opportunity to establish the modern world’s first great republic, and to begin the difficult work of fulfilling the ideals upon which that republic was founded—liberty, equality, natural and civil rights and the privileges, and obligations, of citizenship under the rule of law.

Embracing the idea that the American Revolution was a people’s revolution compels us to consider the varied ideas, hopes and motivations of an enormous range of Americans from all walks of life. And it does something equally important: it forces us to view the Revolution, not from the perspective of the present, but in relation to what came before—the conditions of life before America was, in any meaningful sense, free. It leads us to judge the people of the Revolution not by our standards alone, nor by what we call “the context of their time,” as if that was static and immovable. It leads us to judge them by how far their energy and daring changed the world in which they lived for the better—a fair and just standard against which all should be judged.

“Posterity!” John Adams admonished us in the spring of 1777. “You will never know, how much it cost the present Generation, to preserve your Freedom! I hope you will make a good Use of it.” Our task is to make sure posterity does know how much it cost the revolutionary generation to establish our freedom, and makes good use of it.

Jack D. Warren, Jr.

Above: This extraordinary modern sculpture of Margaret Corbin by Tracy H. Sugg pays tribute to a heroic woman whose sacrifice embodies the commitment that made the American Revolution a people’s revolution (image of the original clay sculpture prior to bronze casting, used by permission of the artist—www.tracyhsugg.com).

The People’s Revolution was presented, under the title The Future of the American Revolution, as the 2021 American Revolution Lecture at the North Carolina Museum of History, an annual series sponsored by the North Carolina Society of the Cincinnati. Watch the lecture online at The Future of the American Revolution.

For more on the ordinary men and women whose drive for personal independence defines the American Revolution, read Margaret Corbin, Revolutionary and The Heroic Jeffrey Brace.

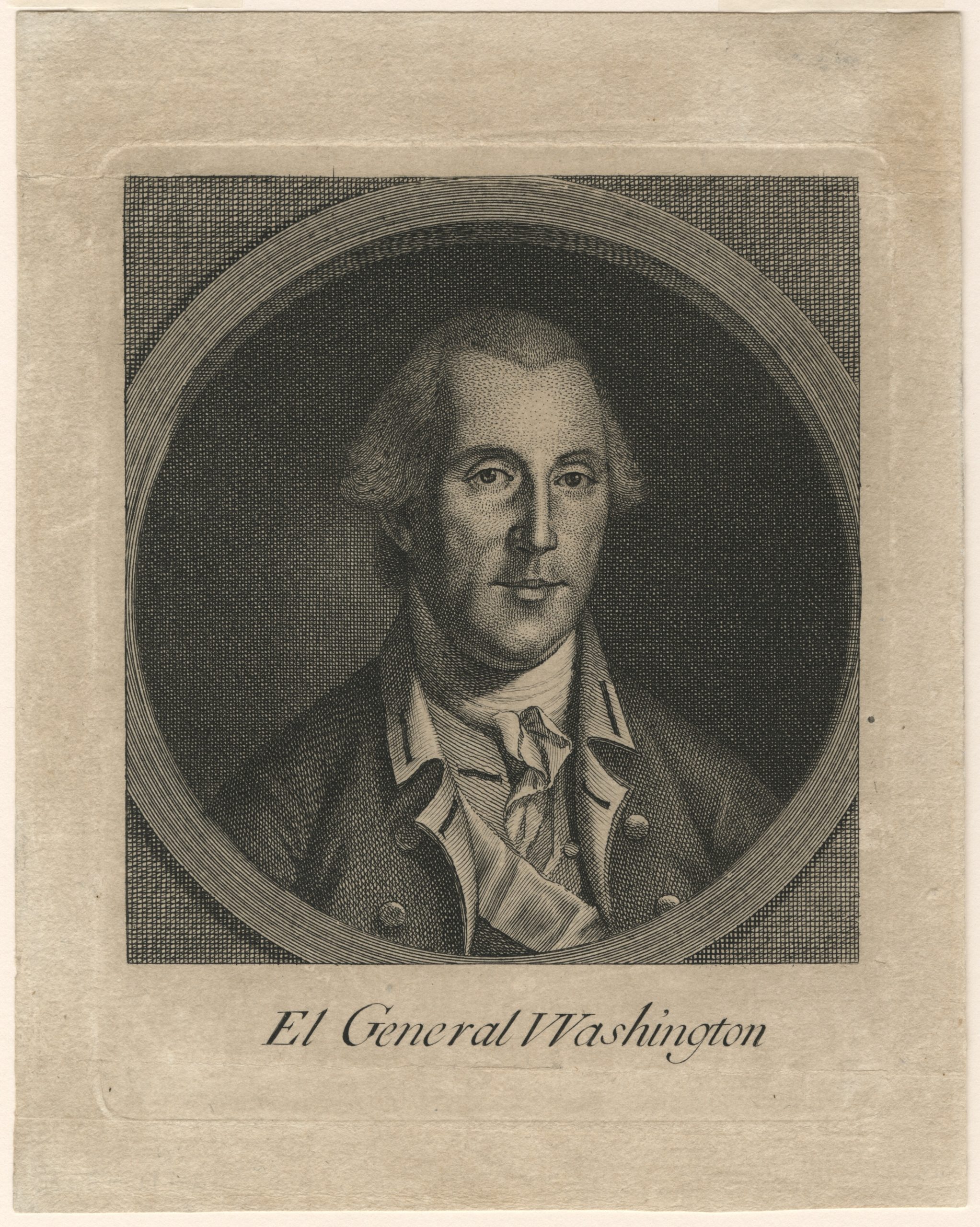

Unlike Peale’s mezzotint, this portrait was created as a line engraving (where the design is cut into a smooth plate and shading is created by hatching, cross-hatching and dots)—but who engraved it and when? No one seems to have figured this out.

Unlike Peale’s mezzotint, this portrait was created as a line engraving (where the design is cut into a smooth plate and shading is created by hatching, cross-hatching and dots)—but who engraved it and when? No one seems to have figured this out.