The American republic was born in war. While statesmen asserted the independence of the United States in an eloquent declaration, tens of thousands of British soldiers and sailors converged on New York to subdue the rebellion by force. Revolutionaries armed with muskets and swords had to wage an eight-year war to free the new nation from British rule and ensure that the promise of independence would be fulfilled.

Supplying its troops with the weapons required to win the Revolutionary War was a critical, complex and ever-present issue for the new American nation. When the war began in 1775, there were few factories in America capable of producing firearms, swords and other weapons—let alone in the quantities necessary to sustain an army for several years. At the height of the war, fifty thousand men served in the Continental Army, with another thirty thousand state and militia troops fighting for the American cause. To arm these soldiers against the well-supplied British regulars, American officials gathered weapons from an array of sources on two continents.

Patriots had begun to amass caches of weapons as tensions grew in the months leading up to the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, seizing British arms from royal storehouses, provincial magazines and supply ships. At the beginning of the Revolution, the army relied on soldiers to bring weapons from home, including hunting guns, militia arms and outdated martial weapons from the French and Indian War. American soldiers also carried weapons captured from the enemy in the field and reissued to Continental and state troops. A growing number of American manufacturers produced weapons on government contracts, as the domestic arms industry expanded to try to meet the demand, but they could not sustain the American troops through a long conflict. Success on the battlefield ultimately depended on the hundreds of thousands of arms supplied by France and Spain. Shipments of arms and ammunition from France began arriving in 1776 and continued for the rest of the war.

A Revolution in Arms features nearly forty weapons of the Revolution—British, French, American, Spanish, Hessian and Scottish armaments drawn largely from the Institute’s collections—as well as accoutrements and tools used to fire and maintain the weapons, and documents that provide context for how these arms were acquired, transported, altered and used. Highlights of the show include examples of the iconic British “Brown Bess” and French Charleville muskets that dominated the battlefields, a Pennsylvania long rifle like those used by Continental Army rifle companies, a Hessian dragoon pistol captured at the Battle of Bennington in 1777, and an elegant American officer’s cuttoe featuring a silver-and-ivory hilt and dog-head pommel made by New York cutler John Bailey. The exhibition also features two important American-made muskets produced at manufactories in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, on loan from the Fredericksburg Area Museum, and several arms from the collection of James L. Kochan, including an extremely rare French Model 1717 rampart musket that was transported to America between 1776 and 1780 and modified at the arsenal in Springfield, Massachusetts, for use by Continental troops.

Explore the Institute’s larger holdings of Revolutionary War armaments and military equipment in Discover the Collections.

British Pattern 1769 Short Land musket

ca. 1769-1777The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of John Sanderson du Mont, New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 1994

Introduced in 1769, this Short Land pattern musket was the standard-issue infantry weapon of the British army at the start of the Revolutionary War. Colonial storehouses contained large numbers of these guns, which patriots seized in the early months of the conflict. The British Short Land pattern musket, also called the Brown Bess, became the most common firearm used by American troops in the Revolution, despite weighing more than ten pounds.

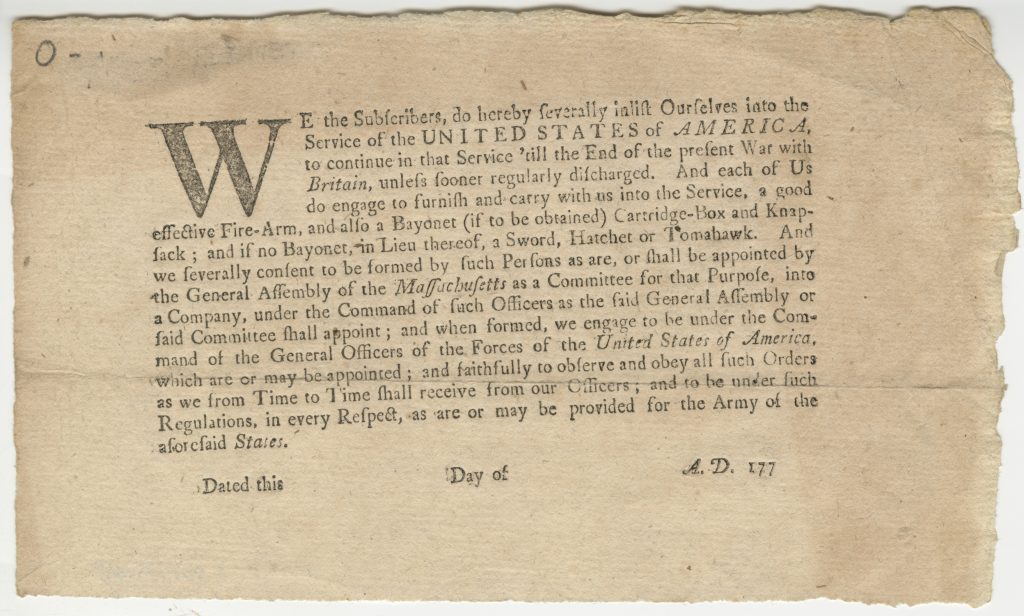

Continental Army enlistment agreement

ca. 1775-1777The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The Continental Army initially expected recruits to provide their own arms and accoutrements. Recruits in Massachusetts who signed this agreement to enlist for the duration of the war declared that “each of Us do engage to furnish and carry with us into the Service, a good effective Fire-Arm, and also a Bayonet (if to be obtained) Cartridge-Box and Knap-Sack ; and if no Bayonet, in Lieu thereof, a Sword, Hatchet or Tomahawk.”

Holster pistols

John Twigg, London, England

ca. 1775The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Alexander Ferguson Anderson, 1966

Officers purchased holster pistols privately from independent gunsmiths—usually in pairs—and carried them in leather holsters draped in front of their saddle. Intended for use as military arms, holster pistols typically reflected contemporary cavalry patterns, with personal preferences incorporated into the design. Major Richard Clough Anderson of the Virginia Continental Line owned this pair of slender holster pistols with octagonal barrels.

Small sword

William Cowell, Jr., Boston, Mass.

ca. 1760The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Isabel K. Jordan, 1978

The small sword, a ubiquitous civilian pattern worn as part of a gentleman’s formal attire, was the most common sword carried by American officers during the Revolution. William Cowell, Jr., assembled this example in pre-Revolutionary Boston, using a silver hilt he made and an imported triangular blade. It was owned by Richard Varick, an officer in the New York Continental Line and aide-de-camp or secretary to Generals Philip Schuyler, Benedict Arnold and George Washington.

French Model 1766 infantry musket

Charleville

ca. 1766-1773The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of John Sanderson du Mont, New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 1978

This model became the most common firearm carried by American troops during the Revolution next to the British Pattern 1769 Short Land musket. Most of the thirty-seven thousand long arms shipped from France to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in early 1777 were the Model 1766 musket. New Hampshire officials appropriated some of those muskets for its own Continental regiments, including this one, which is branded on the barrel “NH 2B No. 520”—having been gun number 520 issued to the Second New Hampshire Regiment.

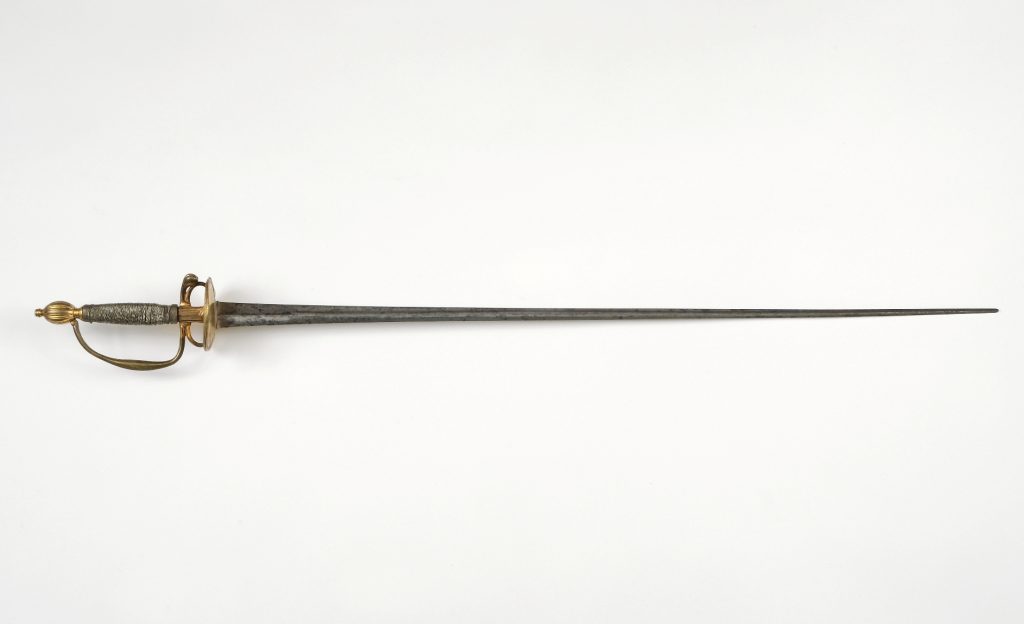

French Model 1767 infantry officer’s sword

ca. 1767The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2011

In 1779, while in France securing additional aid for the Americans, the marquis de Lafayette purchased uniforms, swords and accoutrements for the officers of the Continental Army’s Light Infantry, which he commanded. Among this military equipment was the Model 1767 officer’s sword, known as an épée d’officier. It bears an engraved colichemarde (hollow triangular) blade that was designed only for thrusting, making the weapon impractical in most combat situations.

Spanish Model 1757 infantry musket

Sebas

1774The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum purchase with a gift from Dr. J. Phillip London of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati and Dr. Jennifer London, 2016

In addition to contributing one million livres to the covert shipments of French arms by Roderique Hortalez et Cie., Spain supplied gunpowder and other military stores to the American rebels through agents in New Orleans. Some American troops were supplied with the Spanish Model 1757 musket—the standard Spanish infantry firearm during the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution. This included George Rogers Clark’s Virginia state troops, which carried Spanish muskets on their campaign into Illinois territory in 1779.

Highland broadsword

ca. 1750-1780The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Maj. Ruxton Moore Ridgely, Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1959

The basket-hilt broadsword was an iconic weapon of the Highland Scots in the eighteenth century. During the Revolutionary War, the broadsword was carried by Scottish infantrymen and some British dragoons in the Royal Army, as well as by Scottish immigrants to the Carolinas and Georgia who served in loyalist units. American troops captured Highland broadswords on the battlefield as well as from British supply ships. Nicholas Ruxton Moore, an officer in the Fourth Continental Dragoons in 1777-1778 and the Maryland militia in 1781, acquired this Highland broadsword at some point during the war. Its double-edged blade was made in Germany and imported into Scotland, where a local swordsmith fitted it with a basket hilt.

Hessian dragoon pistol

ca. 1755-1770The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of John Sanderson du Mont, New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 1994

Long, large-caliber dragoon pistols like this one were standard military arms for mounted troops from the German states. The British government bolstered its army for the Revolutionary War by hiring thirty thousand soldiers from principalities like Hesse-Cassel, which inspired the generic term Hessians to refer to all the German troops. The cipher of the ruler of one of these German states is engraved on the brass thumbpiece of this pistol. It was among the Hessian weapons captured by the American forces at the Battle of Bennington in August 1777.

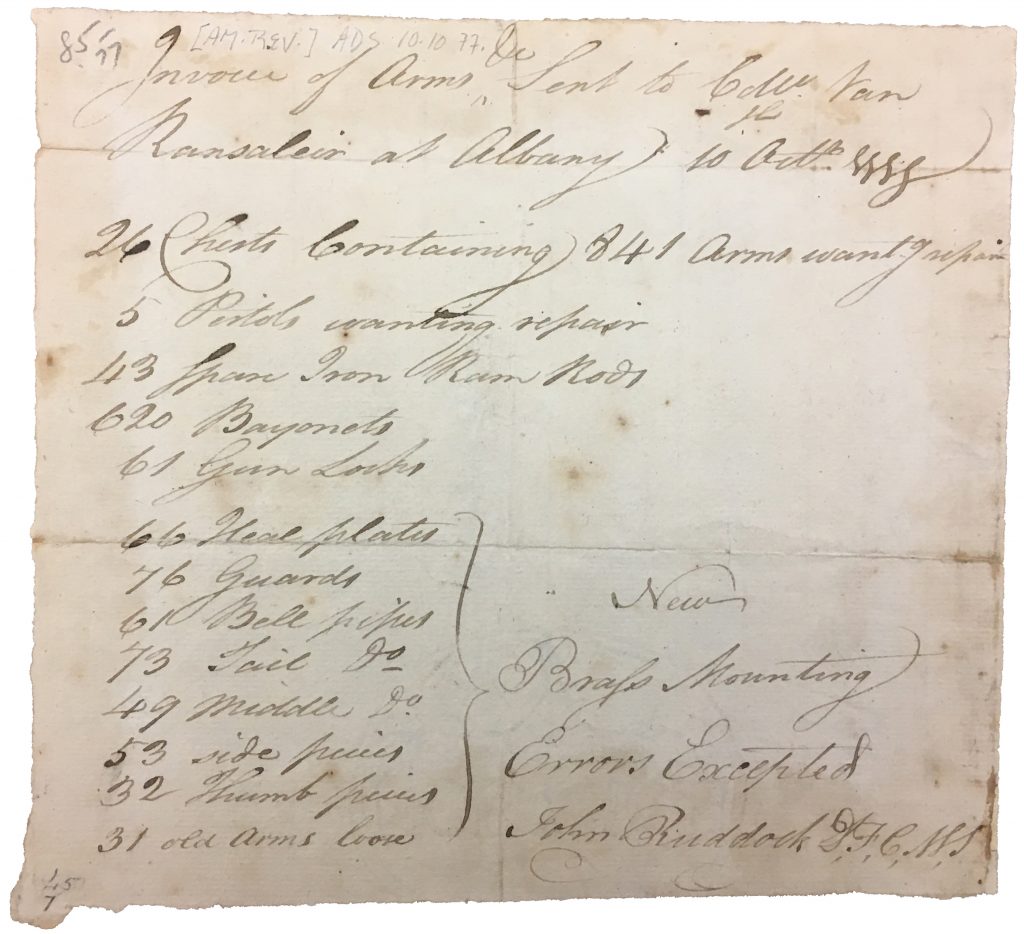

“Invoice of Arms &c. sent to Colo. van Ransaleir at Albany”

John Ruddock, Fishkill, N.Y.

October 10, 1777The Society of the Cincinnati, Library purchase, 1977

To help supply American troops during the Revolution, Congress created Continental arms factories, arsenals and supply depots and paid hundreds of individual craftsmen to repair and manufacture weapons for the army. Just three days after the American victory at Saratoga, John Ruddock, the Continental Army’s deputy commissary of military stores at the Fishkill Supply Depot, compiled this list of arms sent to Colonel Phillip Van Rensselaer, keeper of the arsenal at Albany. The shipment included “26 Chests Containing 841 Arms wanting repair” as well as nearly five hundred newly made brass mountings for firearms.

Pennsylvania long rifle

Possibly Reading, Pa.

ca. 1780-1790The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of John Sanderson du Mont, New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 1994

The most iconic weapon manufactured in America during the Revolution is the long rifle, a slender, lightweight firearm designed for hunting and protection in the wooded, mountainous terrain of the western frontier. The rifle was revered for its accuracy over long distances, but limitations prevented it from being as widely used in wartime as the smoothbore musket. The American long rifle evolved from the German jaeger rifle, which accompanied German immigrants to Pennsylvania and the western frontiers of Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas. The vast majority of American rifles were produced by independent gun makers in Pennsylvania, especially in the Lancaster region.

Horseman's saber

Abraham Morrow, Philadelphia

ca. 1776-1781The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of John Sanderson du Mont, New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 1994

In addition to carbines and pistols, Revolutionary War cavalry troops, or horsemen, were armed with a long saber with a substantial, single-edged blade. This example was made by Abraham Morrow, a cutler in Philadelphia who produced swords on contract for the Continental Army. The initials “RW”—possibly of the sword’s owner—are peck-marked on the outside of the knuckle bow.

Officer's cuttoe and scabbard

John Bailey, Fredericksburgh, N.Y.

ca. 1778The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Dr. Adams Bailey, Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, 1964

Some American officers carried a cuttoe or hunting sword, a short civilian sword that was more effective at displaying rank and status than fighting in battle. John Bailey, a New York cutler originally from Sheffield, England, made this cuttoe with a highly decorated silver hilt—complete with a dog-head pommel and green-tinted ivory grip—and an imported blade. Adams Bailey, an officer in the Second Massachusetts Regiment, purchased this cuttoe and had his name engraved on the silver throat of the scabbard.

Musket

Virginia State Gun Factory, Fredericksburg, Va.

1776Courtesy of Fredericksburg Area Museum

The Virginia State Gun Factory—also known as the Fredericksburg Gun Factory or the Public Gun Factory—was among the first public arms factories established by one of the former British American colonies. Colonel Fielding Lewis and Major Charles Dick established the facility along the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg after the Virginia council approved its creation in July 1775. The Virginia State Gun Factory operated throughout the war, repairing and manufacturing muskets, bayonets and small quantities of gunpowder for Virginia troops.