Click to download the catalog.

Our commitment to the veterans of our time is a legacy of the American Revolution and our commitment, two hundred years ago, to honor and care for America’s first veterans. Over a quarter of a million American men served in the armed forces that won our independence. Between eighty and ninety thousand of them served in the Continental Army, an all volunteer army of citizens. All of these men risked their lives. Those who survived the war became America’s first veterans—the world’s first veterans of an army of free men.

The American republic owed its existence to them, but in the first years after the Revolutionary War, Americans found it difficult to acknowledge that debt, much less honor their service. Most American soldiers returned from their service in the Revolutionary War with nothing more than the personal satisfaction of duty faithfully performed. Following British practice, Congress provided small pensions for men disabled in service. Most men discharged in good health received nothing. The generals who had led them were celebrated as heroes, but ordinary soldiers were rarely honored in the first decades after the war.

It took decades, but Americans gradually realized that the common soldiers of our Revolutionary War were heroes, too. Those who lived to be old men were finally recognized as honored veterans of a revolution that had created the first great republic of modern times. In 1818 Congress decided to award pensions to veterans in financial need, and in 1832 Congress voted to extend pensions to nearly all of the surviving soldiers and sailors of the Revolution. These were the first pensions paid to veterans without regard to rank, financial distress, or physical disability. They reflected the gratitude of a free people for the brave Americans who secured their freedom.

America’s First Veterans brings together paintings, artifacts, prints and documents to address the post-war experiences of the men who won the Revolutionary War—not the famous generals and leading officers whose names appear in histories of the war, but rather the junior officers and enlisted men whose stories are less often told. A centerpiece of the show is John Neagle’s arresting portrait of a destitute veteran of the Revolution, painted in 1830 in the midst of the fight for comprehensive federal pensions for the remaining Revolutionary War veterans. The exhibition also includes one of two reputed examples of the Badge of Military Merit, the Revolutionary War precursor to the modern Purple Heart, on loan from the American Independence Museum, Exeter, NH and the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Hampshire.

This exhibition is supported in part by a generous gift from CACI International.

The companion book to this exhibition, America’s First Veterans, is available in hardcover. Order your copy today.

A Pensioner of the Revolution

John Neagle (1796-1865)

1830The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum purchase, 2017

This somber and arresting portrait depicts a homeless veteran living on the street in Philadelphia named Joseph Winter. The painting attracted popular attention in early 1831, when John Sartain published a mezzotint engraving of the work titled Patriotism and Age, which became a call to the conscience of the nation to care for those who had fought its battles and won its freedom.

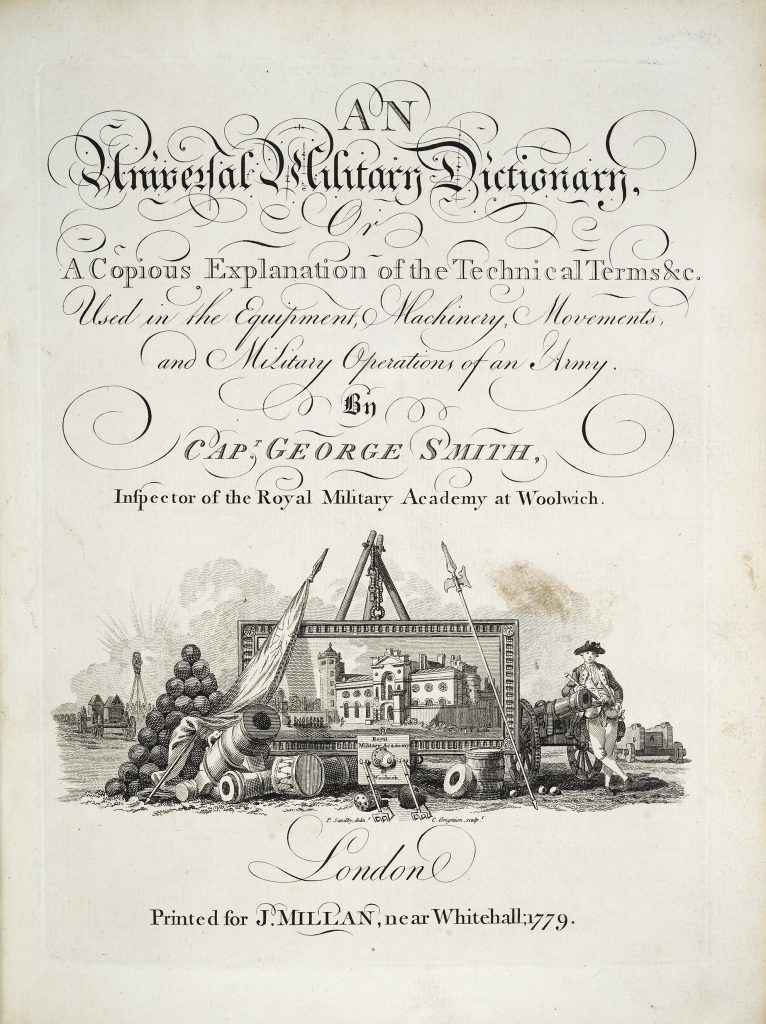

An Universal Military Dictionary

Capt. George Smith

London: Printed for J. Millan, 1779The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The term veteran originated in ancient Rome and was revived in the Renaissance to apply to men distinguished by long and illustrious service to the state rather than to long-serving common soldiers. This military dictionary by Capt. George Smith, inspector of the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, defines a veteran as “a soldier who was grown old in the service, or who had made a certain number of campaigns” and specifies that “Twenty years service were sufficient to intitle a man to the benefit of a veteran.”

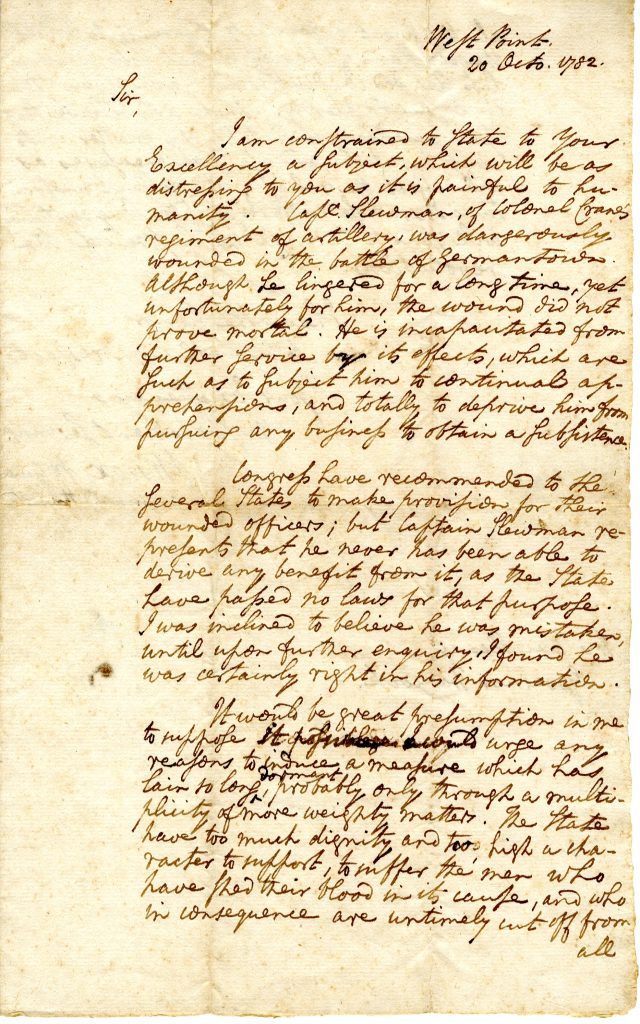

Henry Knox to John Hancock

October 20, 1782The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

In this wartime letter, Henry Knox appealed to Governor John Hancock of Massachusetts for support for Capt. John Sluman of Crane’s Artillery Regiment, who was permanently disabled by wounds inflicted at the Battle of Germantown in 1777. Sluman was awarded a half-pay disability pension of $300 per year from Massachusetts in 1784. Congress assumed responsibility for disability pensions in 1792 and paid Sluman $300 annually until his death in 1816.

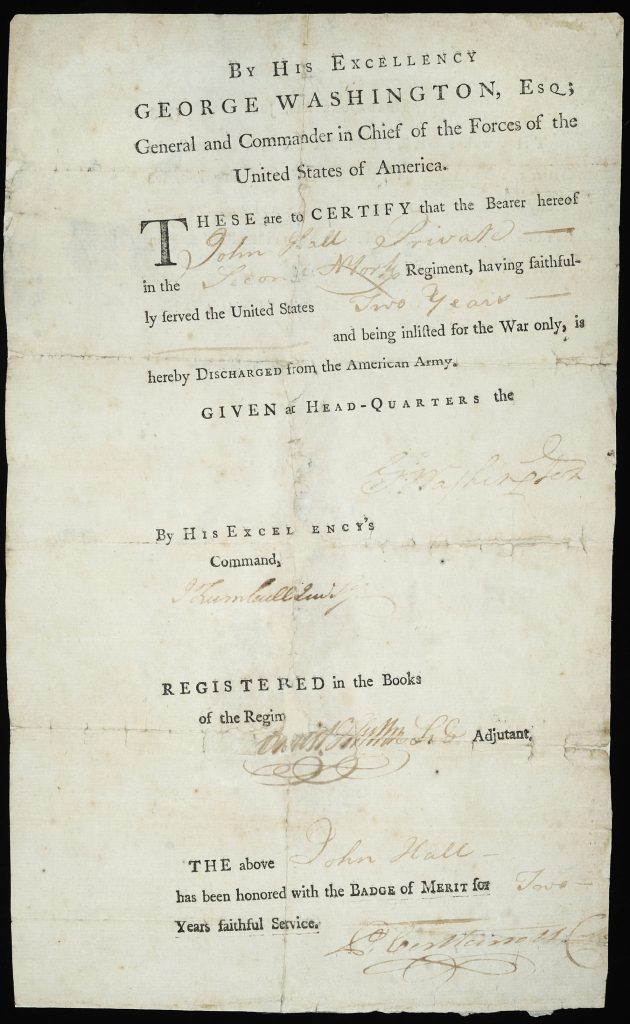

Discharge of Private John Hall

[1783]The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Robert L. Buell, 1966

In accordance with instructions from Congress, the soldiers of the Continental Army who had enlisted for the duration were furloughed in June 1783—and were sent home with no more than one month’s pay in cash and promissory notes for a few months additional pay. John Hall, a private in the Second New York Regiment, received this discharge, noting he “has been honored with the Badge of Merit for two years faithful service.”

Badge of Military Merit

ca. 1782-1783Collection of the American Independence Museum, Exeter, NH and the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Hampshire. Gift of William L. Willey.

George Washington created the Badge of Military Merit—the first American military decoration for enlisted men—on August 7, 1782. The award recognized distinguished conduct and was intended to encourage “virtuous ambition” and “every species of Military merit.” Soldiers honored with the award “shall be permitted to wear on his facings over the left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth, or silk, edged with narrow lace or binding.” Only two reputed examples are known, of which this is one. The decoration fell out of use after the Revolutionary War but was revived in 1932 as the modern Purple Heart.

Society of the Cincinnati insignia owned by Allan McLane

Jeremiah Andrews (d. 1817)

ca. 1784-1791The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum purchase, 2018

The Society of the Cincinnati was the nation’s first veterans organization, founded by officers of the Continental Army to preserve their fellowship, perpetuate the memory of the American Revolution, and maintain pressure on Congress to fulfill the promises made to them. The Society’s insignia, known as the Eagle, was the first American military decoration in the familiar modern form—a metal badge suspended from a ribbon. This example was owned by Capt. Allan McLane (1746-1829), a distinguished Delaware officer.

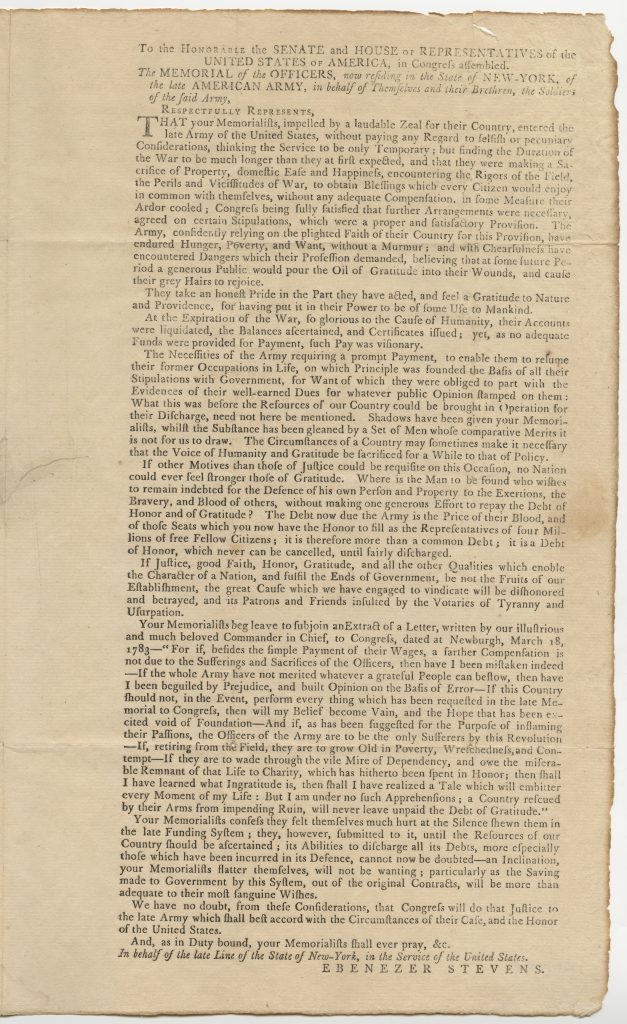

The Memorial of the Officers, now Residing in the State of New-York, of the Late American Army

New-York, September 1792The Society of the Cincinnati, Library purchase, 1975

The Society of the Cincinnati and its members petitioned Congress repeatedly to fulfill its wartime promise of half pay for life for officers. This memorial of veteran officers residing in New York was printed over the signature of Ebenezer Stevens (1751–1823), a Rhode Islander who rose through the commissioned ranks to become a lieutenant colonel of artillery. Congress did not make a conclusive settlement of the veteran officers’ claims until 1828.

Bryan Rossiter

John Trumbull (1756-1843)

ca. 1806-1808New York State Society of the Cincinnati

Veteran enlisted men like Bryan Rossiter (1760-1834), a sergeant in the Continental Army, waited decades to secure what was due to them. Rossiter settled in New York City after the war. As a veteran non-commissioned officer, he was not eligible to join the Society of the Cincinnati, but the New York branch appointed him sergeant at arms in 1801. John Trumbull’s portrait of Rossiter depicts him in his sergeant at arms uniform with two white chevrons on his left sleeve, indicating that Rossiter had been awarded the Badge of Merit.

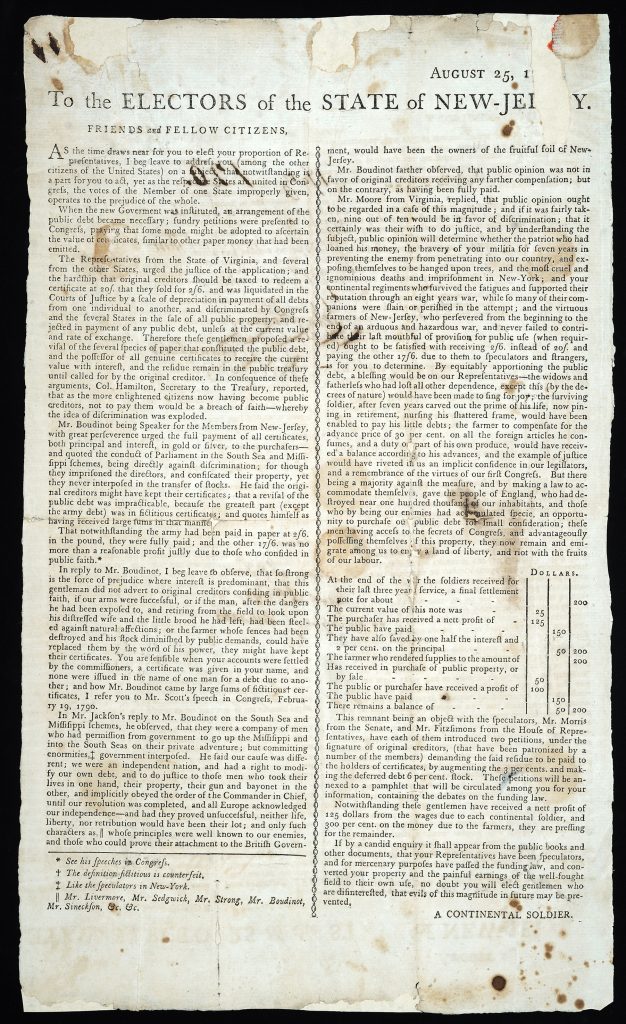

To the Electors of the State of New-Jersey

“A Continental Soldier” [James Blanchard]

[Norfolk, Va.], August 25, 1792The Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland

Most soldiers received debt certificates instead of pay when they were discharged from the army. Needing cash to support themselves, some veterans sold the certificates to speculators at a small fraction of their face value. Among the most fiercely debated issues of the early 1790s was whether the new federal government should pay the full value of those certificates to the speculators who had bought them up at a discount, or “discriminate” between speculators and original holders—mainly Continental Army veterans—and pay at least some of the value to the soldiers who had earned them. This broadside circulated in New Jersey and elsewhere during the fall of 1792 to influence voters to elect candidates who supported discrimination.

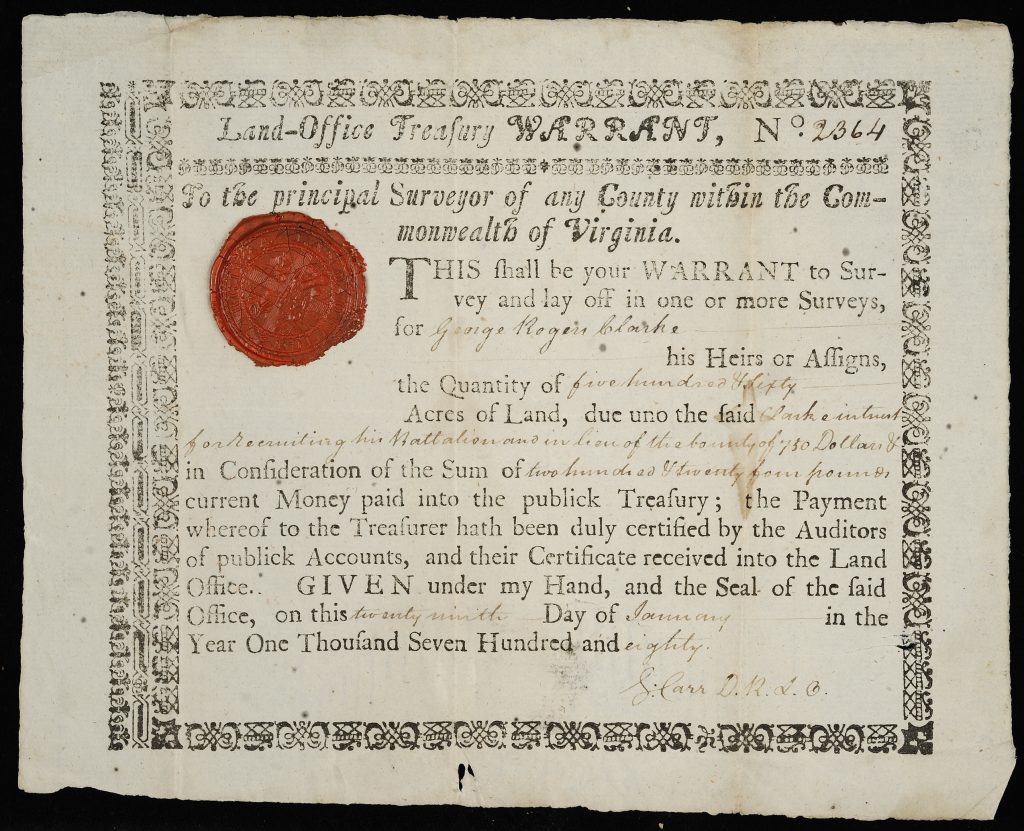

Land warrant issued by the Commonwealth of Virginia to George Rogers Clark

January 29, 1780The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The Continental Congress and some of the states promised soldiers land warrants as an inducement to secure the services of enlisted men and officers. The Commonwealth of Virginia issued this land warrant for 560 acres to George Rogers Clark (1752-1818) in January 1780 “in trust for recruiting his Battalion and in lieu of the bounty of 750 Dollars.” A land warrant was a license to survey and apply for a grant of previously unclaimed land in a specific area.

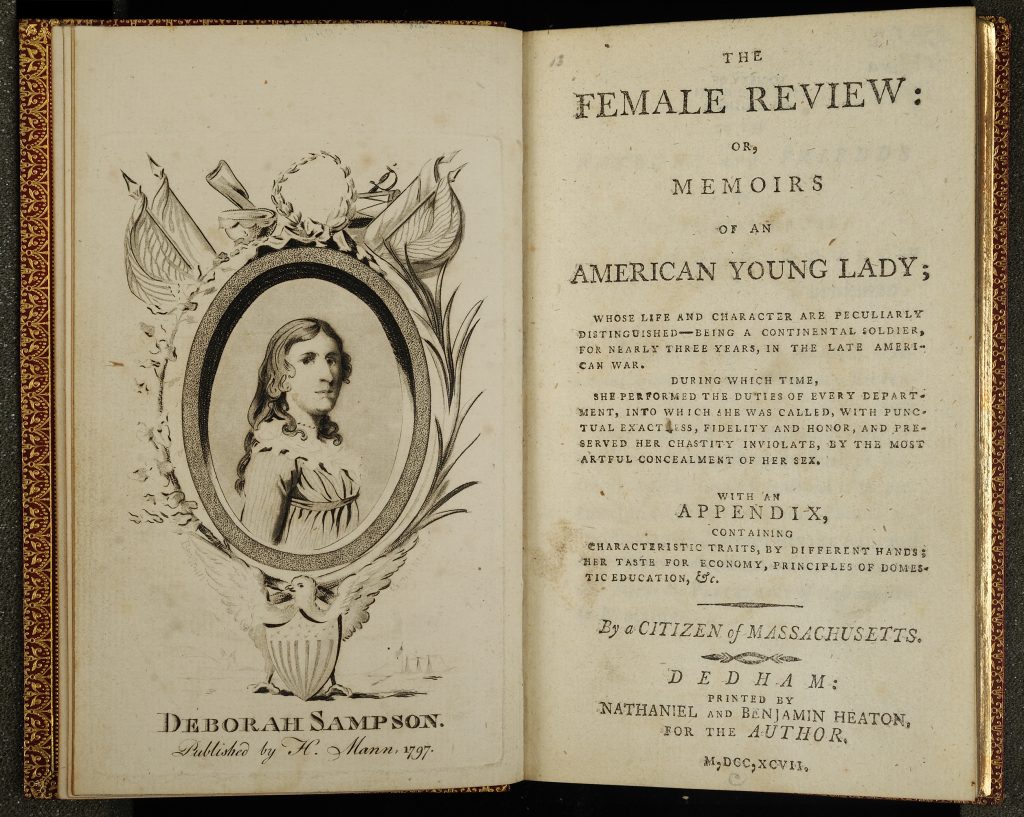

The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady

“A Citizen of Massachusetts” [Herman Mann]

Dedham, Mass.: Nathaniel and Benjamin Heaton, for the Author, 1797The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Deborah Sampson (1760-1827) enlisted in the Massachusetts Continental Line in May 1782 using the name “Robert Shurtleff.” Mixing fact with romantic inventions, this imaginative account of Sampson’s wartime service was published to support her case for a pension. In 1805 she received a disability pension of $4 a month, which she relinquished to accept a pension of $8 a month awarded under the Pension Act of 1818.

Ebenezer Huntington

John Trumbull (1756-1843)

ca. 1835The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2018

Ebenezer Huntington (1754-1834) of Norwich, Connecticut, was one of the highest-ranking veterans to receive a pension. He retired from the Continental Army in 1783 as a lieutenant colonel and was commissioned a brigadier general during the Quasi-War with France in 1798, but he fell into genteel poverty in the 1810s. John Trumbull depicted him in the uniform of a brigadier general in this oil-on-panel portrait.

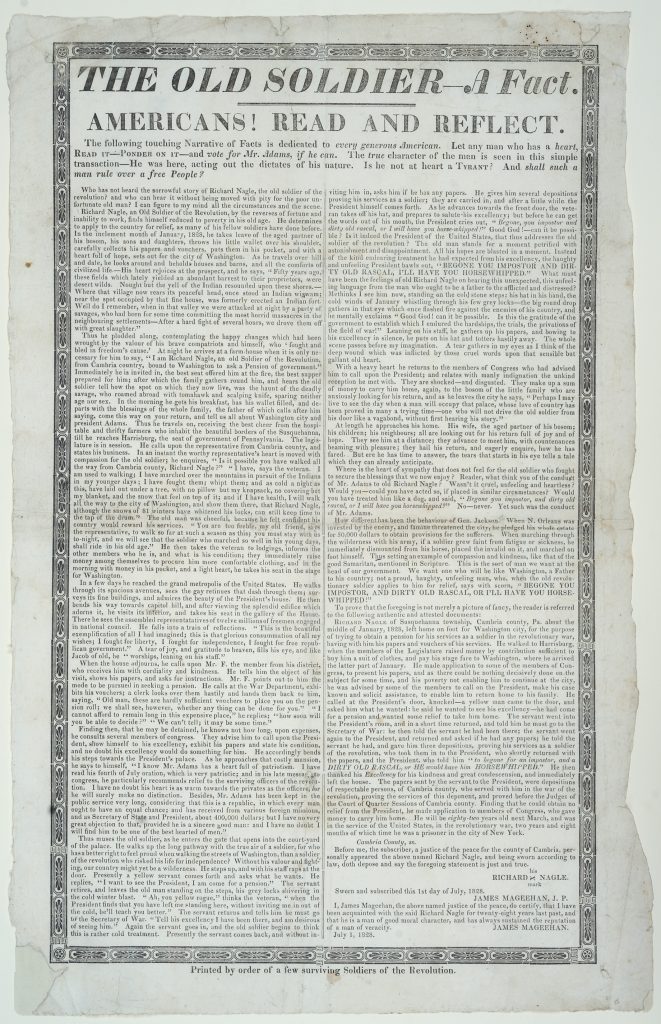

The Old Soldier—A Fact

Printed by order of a few surviving Soldiers of the Revolution, 1828The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This broadside from the presidential campaign of 1828 relates the mistreatment of a Revolutionary War veteran seeking a pension by John Quincy Adams and assures readers that Andrew Jackson would correct the injustices of the Adams administration toward veterans. “Where is the heart of sympathy,” the broadside asks, “that does not feel for the old soldier who fought for the blessings we now enjoy?”

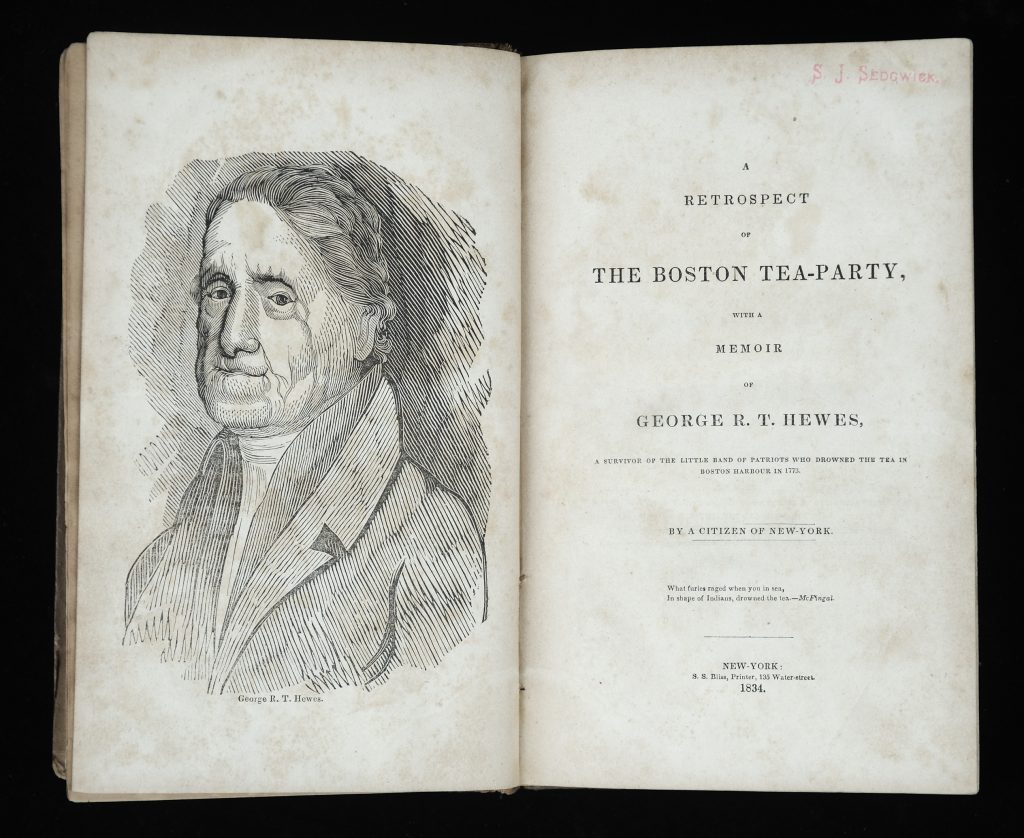

A Retrospect of the Boston Tea-Party, with a Memoir of George R.T. Hewes

“A Citizen of New-York” [James Hawkes]

New-York: S.S. Bliss, printer, 1834The Society of the Cincinnati, Library purchase, 1990

Common soldiers and sailors began publishing accounts of their Revolutionary War experiences in the first decades of the nineteenth century. George Robert Twelves Hewes (1742-1840) witnessed the Boston Massacre and participated in the Boston Tea Party. During the war he served aboard a privateer for three months, as well as in the Massachusetts militia. This book chronicling his experiences was the first work to refer to the destruction of the East India Company tea as the “Boston Tea Party.”

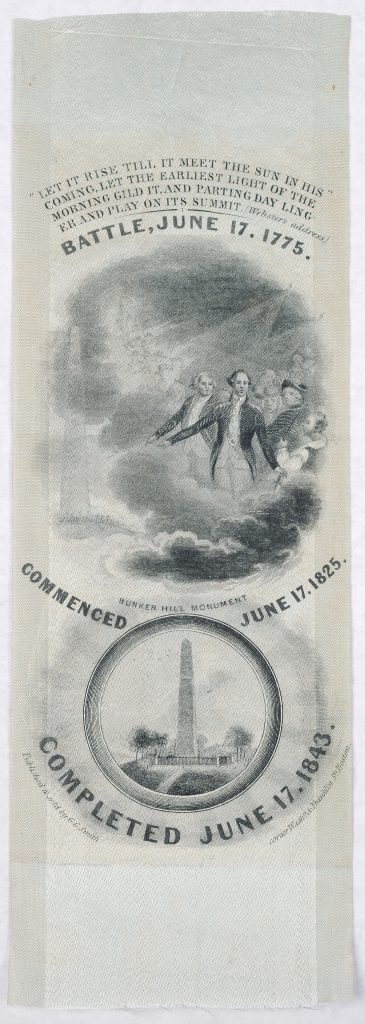

Ribbon commemorating the Bunker Hill monument

G.G. Smith, Boston

1843The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum purchase, 2019

When it was completed in 1843, the Bunker Hill Monument was the most ambitious Revolutionary War monument in the United States. This printed silk ribbon commemorates its dedication. It bears a short passage from Daniel Webster’s dedication speech and a scene of Revolutionary War veterans in the clouds looking down approvingly on the monument.

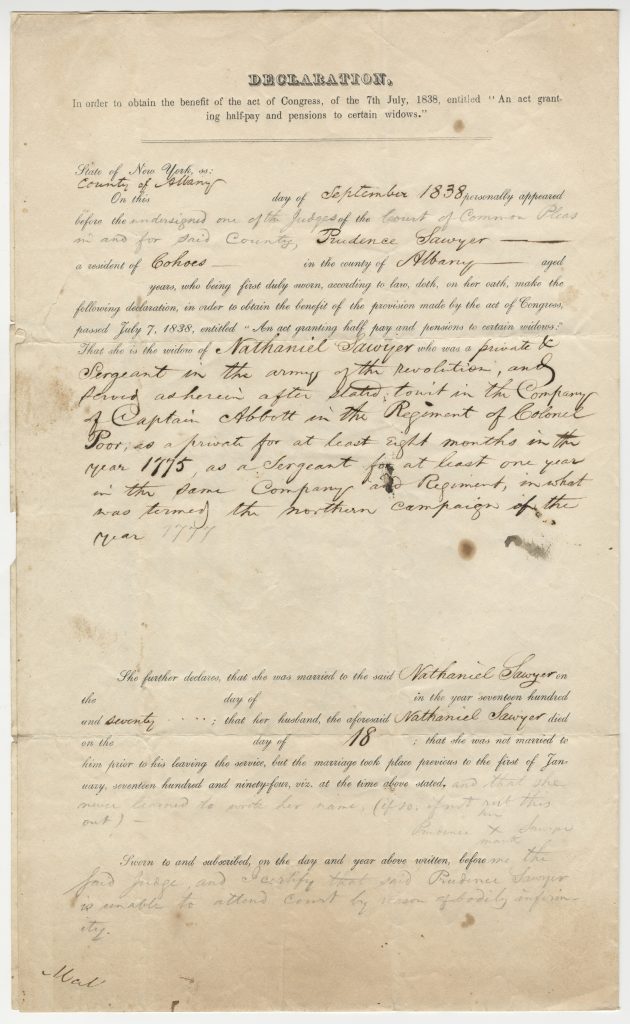

Declaration of Prudence Sawyer

September 1838The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Prudence Sawyer (1757-1839) was the widow of a Massachusetts veteran, Nathaniel Sawyer. This draft declaration supported her application for a widow’s pension in 1838. With gaps and inconsistencies in the details, the application was rejected in 1839 for lack of evidence.

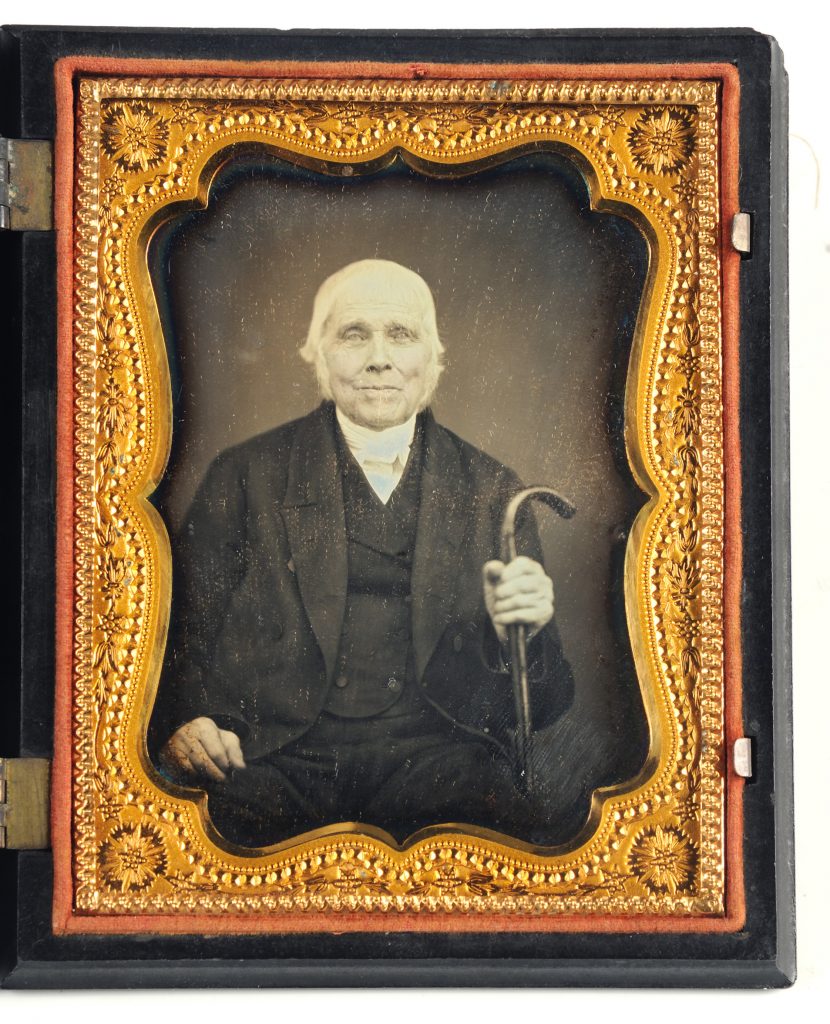

Daguerreotype of George Warner, Jr.

ca. 1855The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum purchase, 2016

George Warner, Jr., of Rupert, Vermont—said to be the last surviving veteran of the Battle of Bennington—was one of hundreds of Revolutionary War veterans who lived into the age of photography. The first photographic portraits of Revolutionary War veterans were daguerreotypes, the most common photographic process of the late 1840s and 1850s.

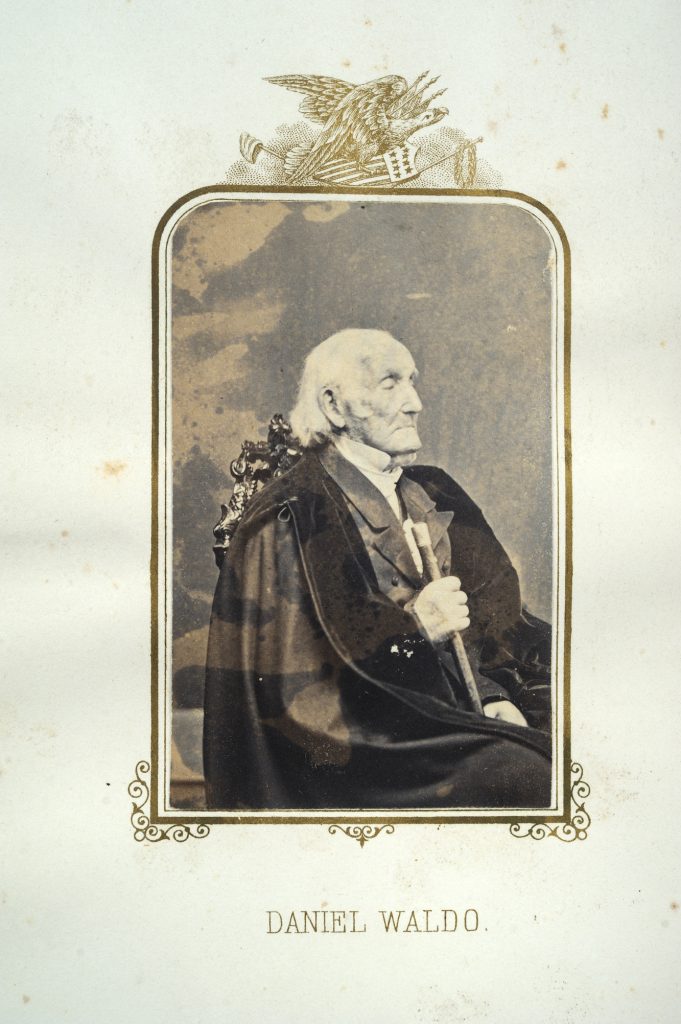

The Last Men of the Revolution

E.B. Hillard

Hartford, Conn.: N. A. & R. A. Moore, 1864The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

At the height of the Civil War, Elias Brewster Hillard (1825-1895), a Congregationalist minister from Connecticut, interviewed the seven men he believed were the last living veterans of the Revolutionary War for his book The Last Men of the Revolution. The book included a photograph of each veteran, taken by Nelson and Roswell Moore of Hartford. Pictured here is Daniel Waldo (1762-1864) of Syracuse, New York, who served in the Connecticut militia during the war.