Click to download the catalog.

American military doctors who joined the cause for independence faced formidable odds. Of the 1,400 medical practitioners who served in the Continental Army, only about ten percent had formal medical degrees. The majority of the rest had learned their practice through an apprenticeship with an established physician. Most were young men at the beginning of their careers. Few had prior experience of war. Their civilian practices had not prepared them for the grim realities of warfare in eighteenth-century America, where far more soldiers under their care would die from disease and infection than would be killed on the battlefield.

Undaunted by these challenges, the healers played as critical a role in the war’s outcome as that of the warriors on the front lines. The field of military medicine was in its infancy at the time of the American Revolution. A generation earlier, Sir John Pringle had transformed medical care in the British army by emphasizing the need for order, cleanliness, sanitation and ventilation in military hospitals. Published a century before the discovery of microbes and antibiotics, Pringle’s Observations on Diseases of the Army was a pioneering work in the prevention of contagion and cross-contamination in treating the sick and wounded. Working under constrained and often brutal conditions—and with a perpetual shortage of medicines, supplies and personnel—American military doctors drew from Pringle and other writers to forge a system of medical care for the army based in the prevailing science of the time.

Each regiment of the army was staffed with a surgeon and surgeon’s mates who provided battlefield triage and critical care. The Hospital Department, created by Congress in July 1775, oversaw a more extensive staff of directors, physicians, purveyors and apothecaries who were responsible for managing and supplying the network of hospitals established across the states. With no clear chain of command between the department and the regiments, the delivery of adequate care to the troops was beset with administrative and logistical problems. Despite these obstacles, the medical practitioners kept their focus on their patients, working tirelessly to improve their condition and ease their suffering. In recognition of their service, Congress granted the army’s doctors the same rank and benefits as officers of the line.

After the war, most veteran military doctors returned to civilian practice. Several became leaders in their field, building upon the knowledge gained from their wartime experiences to promote reforms and advancements that would shape American medical practice for the next generation.

Drawn principally from the Institute’s collections of rare books, manuscripts, portraits and artifacts, Saving Soldiers examines medical practice in the Continental Army and the experiences of surgeons and their patients under the dire conditions of war. Featured are several medical treatises published in America during the Revolution, some bearing the ownership inscription of a Continental Army surgeon. The faces of the medical practitioners are represented by several contemporary portraits, including an exquisite portrait miniature of naval surgeon Nathan Dorsey by Charles Willson Peale, on loan from his descendants. A keystone of the exhibition is a copy of the rare pamphlet by Benjamin Rush, Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers, published by Congress in 1778 for distribution to the officers of the army. A Continental Army hospital register and a similar journal for a ship’s sick bay list patients, treatments and outcomes. Also on view are medical instruments and other artifacts associated with medical men whose heroic work contributed to the achievement of American independence.

Special thanks to the top supporters of this exhibition:

German Pierce Culver, Jr.

The Delaware State Society of the Cincinnati

Roy Alton Duke, Jr.

The New York State Society of the Cincinnati

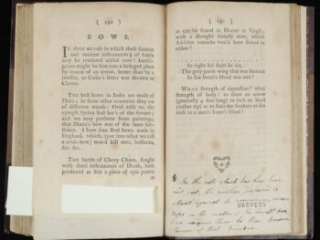

Military Collections and Remarks

Robert Donkin

New-York: Printed by H. Gaine, 1777The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Throughout the war Americans harbored fears that the enemy was deliberately causing the spread of smallpox through the military and civilian population. Although it is difficult to prove specific cases of such biological warfare, there is fascinating evidence in this book by a British military officer, published in New York in 1777. In his chapter on “Bows,” Robert Donkin added a footnote: “Dip arrows in matter of small pox, and twang them at the American rebels, in order to inoculate them; this would sooner disband these stubborn, ignorant, enthusiastic savages, than any other compulsive measures. Such is their dread and fear of that disorder!” The audaciousness of Donkin’s suggestion did not go unnoticed, and the passage has been excised in nearly every known copy of his book.

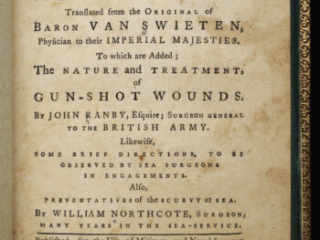

The Diseases Incident to Armies, with the Method of Cure

Gerard, Freiherr van Swieten

Philadelphia: Printed and sold, by R. Bell, 1776The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

As the war began, American publishers sought out medical texts to meet the needs of the new army’s medical corps. This translation of the work of a prominent Dutch military physician was published in Philadelphia in 1776. The manual also included excerpts from the works of two British authors—John Ranby on the nature and treatment of gunshot wounds and William Northcote on the prevention of scurvy at sea.

Lancet owned by Justus Storrs

Made by Benjamin Hanks, Mansfield, Conn.

1774The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold Justus Craft, Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut, 1965

Military physicians used lancets to draw out blood, score the skin for inoculation, and drain infections. This brass and iron example, inscribed with the name of its maker, Benjamin Hanks, belonged to Justus Storrs, a surgeon’s mate in the Connecticut Continental Line.

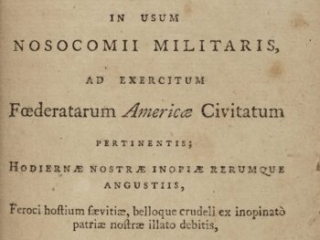

Pharmacopoeia simpliciorum et efficaciorum

William Brown

Philadelphiae: Ex officina Styner & Cist, 1778The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

William Brown, physician general of the Middle Department of the Continental Army, compiled this handbook of formulas for medicinal preparations while stationed at Lititz, Pennsylvania, in 1778. Known as the “Lititz Pharmacopoeia,” it set the standard for the military hospitals across the states. Acknowledging the chronic shortages of medicines, the author emphasized “such formulae as it is always in our power to obtain.”

Mortar and pestle owned by William Chowning

18th centuryThe Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of William J. Chewning, Jr., Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, 1959

This ceramic and wood mortar and pestle used in the preparation of medicines belonged to William Chowning, a surgeon’s mate in the Virginia State Navy.

Plain Concise Practical Remarks on the Treatment of Wounds and Fractures

John Jones

New-York: Printed by John Holt, 1775The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Dr. John Jones, a professor of surgery at King’s College in New York, was a veteran of the French and Indian War. Recognizing the inexperience of the new recruits to the medical corps, he published this manual “for the Use of young Military Surgeons in North-America” in New York in 1775. A second expanded edition, which included advice for naval surgeons, was published in Philadelphia the following year. This copy belonged to Dr. Henry Latimer, who directed the Continental Army’s “Flying Hospital,” a mobile surgical unit.

A Treatise, or Reflections, Drawn from Practice on Gun-shot Wounds

Henry-François Le Dran

London: Printed for John Clarke, 1743The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Early in his career, Dr. John Jones studied in Paris under Henry-François Le Dran, one of France’s leading military surgeons. Le Dran was a proponent of the Petit tourniquet as standard equipment for treating massive wounds and amputation. This English translation of Le Dran’s Traité ou Reflexions Tirées de la Pratique sur les Playes d'Armes à Feu bears the signature of Charles McKnight, who served as surgeon-general of hospitals in the Middle Department.

Barnabas Binney (1751-1787)

Artist unknown, possibly William Verstille

ca. 1779-1783The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Emily V. Binney, 1955

Barnabas Binney left his native Boston in 1774 to study medicine at the College of Philadelphia. In May 1776, shortly after earning his degree, he was commissioned a surgeon in the Hospital Department of the Continental Army. Dr. Binney spent more than seven years treating sick and wounded American soldiers. This watercolor portrait miniature painted during the war—possibly for Binney’s wife, Mary—depicts him in the uniform worn by Continental Army surgeons.

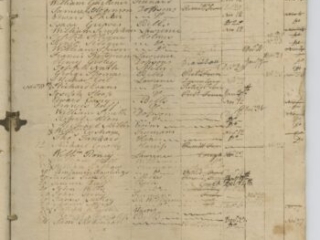

Register of patients admitted to a Continental Army hospital

September 16, 1778-early January 1779The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Continental Army physicians relied on registers like this to account for and monitor patients under their care. This register lists patients according to their individual regiments and conveys important information pertaining to soldiers’ illnesses or injuries, with the malady crossed off when the patient was discharged. The inclusion of a column for “Deserted” along with “Fit for Duty” or “Died” is a telling indicator of the connection between health and morale within the army.

David Olyphant (1720-1805)

By Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872)

ca. 1818-1821The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Murray Olyphant, Jr., New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 1985

A graduate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, David Olyphant came to America following the Battle of Culloden (1746) and settled in South Carolina. From the early years of the Revolutionary War, he directed a general hospital in the Charleston area. He was appointed director general of hospitals in South Carolina in May 1781, and shortly thereafter he and his hospital staff were taken prisoner by the British during the Siege of Charleston. Following his release, Olyphant administered a hospital for American prisoners still held in Charleston. After the war, he moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where he continued to practice medicine. Dr. Olyphant’s son, David Washington Cincinnatus Olyphant, commissioned this posthumous oil portrait from American artist and inventor Samuel F. B. Morse.

Nathan Dorsey (1754-1806)

By Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

ca. 1775On loan from the Corinne Dorsey Onnen Trust

Nathan Dorsey served as a naval surgeon from 1776 until the end of the war. After his ship Raleigh endured several hours of cannon fire in 1778, he and fellow surgeons performed hours of amputations and wound dressing in the cramped, dark quarters. Later, as a prisoner on HMS Jersey, Dr. Dorsey tended to his fellow captives and was allowed to travel by boat to the hospital ship and to New York for medicine. Dr. Dorsey was the last surgeon to tend to a mortally wounded man in the war. This watercolor portrait miniature by Charles Willson Peale depicts Dr. Dorsey at about age twenty-one, shortly before he entered service in the Continental Navy.

Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers: Recommended to the Consideration of the Officers of the Army of the United States

Benjamin Rush

Lancaster, Pa.: Printed by John Dunlap, 1778The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Benjamin Rush’s essay emphasizing the importance of diet, dress, and camp hygiene to the maintenance of soldiers’ health was first published in the Pennsylvania Packet in September 1777. At the urging of Gen. Nathanael Greene, it was republished the following year in pamphlet form by John Dunlap, who had followed Congress to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, during the British occupation of Philadelphia. The Board of War ordered four thousand copies to be distributed to the officers of the army.

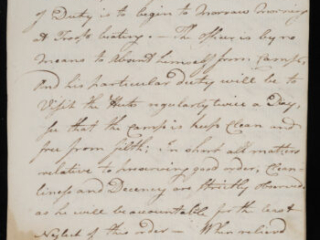

Orderly book of the Sixth Pennsylvania Regiment

Kept by Capt. Jacob Bowers

January 1-April 27, 1779The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This regimental order of January 13, 1779, directs the appointment of a subaltern officer, whose “particular duty will be to visit the Huts regularly twice a Day, see that the Camp is kept Clean and free from filth; in short all matter relative to preserving good order, Cleanliness and decency are strictly observed, as he will be accountable for the least Neglect of this order.”

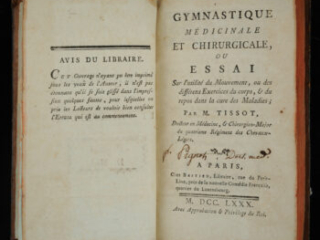

Gymnastique Médicinale et Chirurgicale

Clément Joseph Tissot

A Paris: Chez Bastien, Libraire, 1780The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

French military physician Clément Joseph Tissot pioneered the field of therapeutic exercise in the treatment of disease. His treatise on the subject, published in France in 1780, prescribed specific exercises for certain conditions and illnesses, the duration and intensity of which were to be adapted to the age and temperament of the patient. He warned of the dangers of too much bedrest, even in the treatment of such debilitating diseases as smallpox. He also discussed in detail the benefits of a great variety of sports to the maintenance of good health.

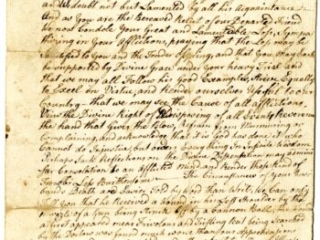

Edward Paine, Nathaniel West, and George Hubbard to Priscilla Birge

November 17, 1776The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This letter from Capt. Jonathan Birge’s fellow officers to his wife, Priscilla, informs her of his death. Jonathan Birge, a Connecticut captain during the New York Campaign, was wounded in his left shoulder on October 28, 1776, “by a muzzle of a gun being struck off by a cannon ball” during the Battle of White Plains. He died from his wounds on November 10 after the doctor “found the wound much worse than our apprehensions.” Captain Birge was forty-two years old and left behind Priscilla and six children.

“Anchor’d in the haven of Rest”

Souvenir maker unknown

20th centuryOn loan from Glenn A. Hennessey, who represents Jabez Smith, Jr. in the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut

Jabez Smith, Jr., served as lieutenant of marines on the Continental ship Trumbull, perishing aboard ship in 1780 in a renowned battle with the British privateer Watt. An officer who participated wrote of the engagement, “It is beyond my power to give an adequate idea of the carnage, slaughter, havock and destruction…I hope it won’t be treason if I don’t except even Paul Jones…we may dispute titles with him.” Smith was laid to rest in Boston’s Granary Burying Ground, where today he lies near Crispus Attucks and Paul Revere. His headstone was topped with a handsome bas relief artwork depicting the ship Trumbull, a carving which has since become a symbol for the cemetery and reproduced on a variety of souvenir plaques, memorializing the grief felt for all the fallen patriots.

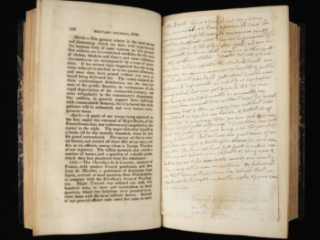

A Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783

James Thacher

Boston: Published by Richard & Lord, 1823The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Tipped into this family copy of Thacher’s Military Journal is a page from his original diary that reads: “We have been several times without meat for several successive days & then as many days without bread, & without forage for our horses, & destitute of medicine & necessary stores for our sick soldiers. These complicated sufferings & privations are such that the patience of our army is on the point of being exhausted. But we have one great consolation, we have a Washington for our Commander. In him we have full faith & entire confidence we believe him capable of doing more & better for us & for the cause of our country than any other man in existence.”

Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia owned by James Tilton

Made by Jeremiah Andrews (d. 1817)

ca. 1784-1791The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Elizabeth Tilton Beaudrias, 2021

James Tilton, a doctor from Dover, joined the Delaware Regiment as a surgeon in January 1776. He witnessed the battles of Long Island and White Plains, and the retreat through New Jersey. In April 1777, Dr. Tilton was appointed as a Continental Army hospital physician and served in that role until the end of the war. He is most renowned for insisting on separating the sick from the wounded to prevent the spread of disease. After the war, Dr. Tilton joined the Delaware State Society of the Cincinnati and was elected its first president. This gold and enamel Eagle insignia, owned and worn by Dr. Tilton, was one of the first Society of the Cincinnati insignias made in America and represents his membership in the Society and his service during the war.