The War of the American Revolution was conducted mainly at sea and its outcome was ultimately determined by naval power.

The war involved the two greatest naval powers in the world—Britain and France—in a maritime conflict of unprecedented scale. The two navies deployed more than 1,200 warships, 25,000 naval cannons and more than 300,000 sailors in a conflict that spanned the globe. The naval war reached from the Caribbean to the Bay of Bengal and from the North Sea to the South Atlantic. The power of the naval forces deployed by Britain and France was staggering. One ship of the line could concentrate more firepower than the entire Continental Army. The British navy deployed more than one hundred of these ships. The fleet commanded by Admiral de Grasse at the Battle of the Chesapeake could deliver more than twenty times the firepower of the combined armies of Washington and Rochambeau. The strategic importance of naval power was clear to the war’s greatest leader. “Without a decisive naval force we can do nothing definitive,” George Washington wrote to Lafayette. “And with it, everything honorable and glorious.”

The American Revolution at Sea brought together selected books, pamphlets, broadsides, manuscripts and engravings from the Society of the Cincinnati’s Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection—which documents the art of war on land and sea in the age of the American Revolution—with art and artifacts from the Society’s museum collections.

This exhibition was made possible by the generous support of Dr. J. Phillip London of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati (a graduate of the United States Naval Academy and a retired United States Navy captain) and his wife, Dr. Jennifer London.

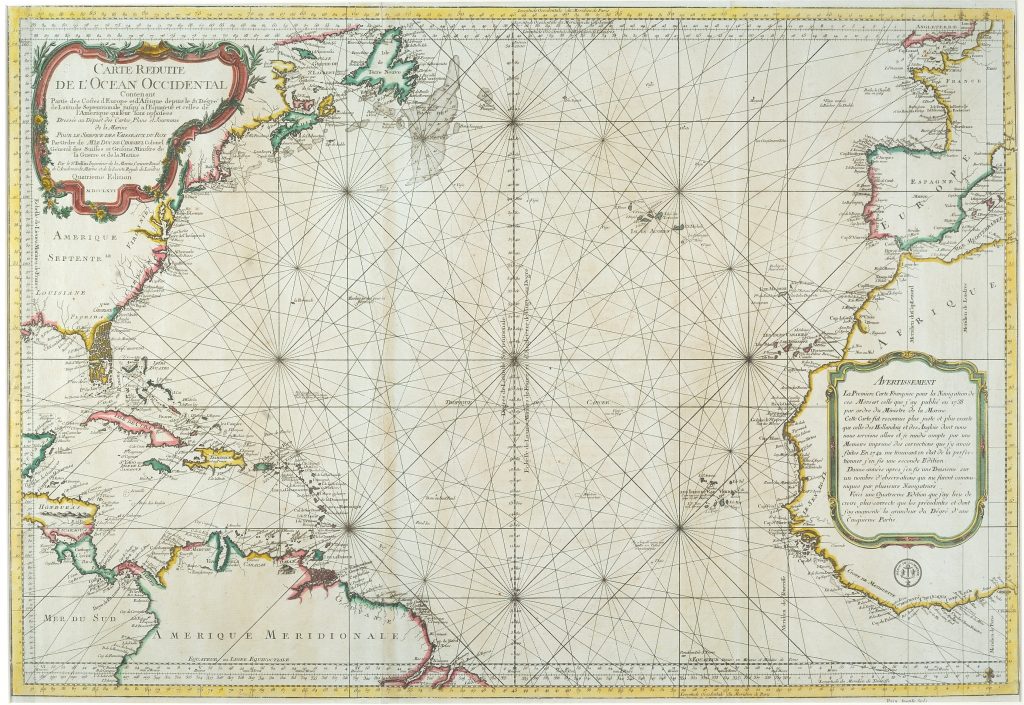

Carte Réduite de l’Ocean Occidental

Jacques-Nicholas Bellin

Paris: Dépôt de la Marine, 1766The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

When France joined the war in June 1778, the War of the American Revolution became a struggle for naval supremacy in the Atlantic world. The French navy challenged Britain for control of the English Channel, the Caribbean, Gibraltar and the coast of North America. American privateers cruised the North American coast, and the tiny Continental Navy attacked British shipping as far away as the North Sea. This map of the Atlantic was the work of Jacques-Nicholas Bellin, one of the most distinguished cartographers of the eighteenth century.

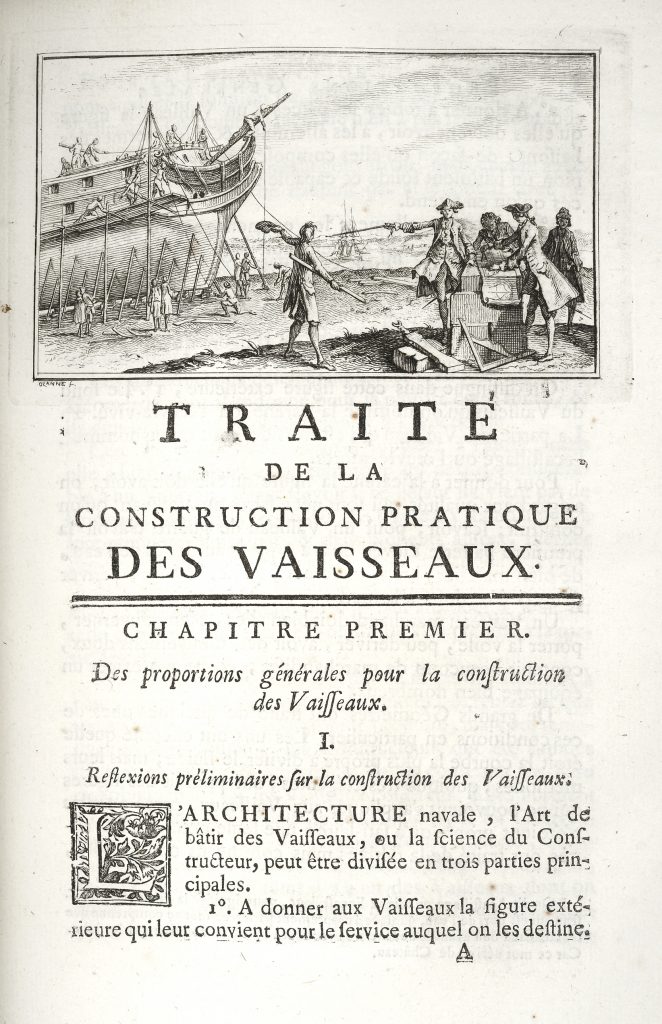

Elémens de l’Architecture Navale, ou, Traité Pratique de la Construction des Vaisseaux

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau

Paris: Chez Charles-Antoine Jombert, 1752The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau’s Elémens de l’Architecture Navale was one of the most important treatises on naval engineering of the eighteenth century and reflected extraordinary sophistication of French naval architecture in the middle decades of the eighteenth century. French naval architects and shipwrights employed the most advanced mathematics and engineering principles, designing and building ships that were faster and more maneuverable than those of their British rivals.![Click for a larger view. Marine Militaire, ou Recueil des Differens Vaisseaux qui Servent à la Guerre, Nicolas-Marie Ozanne, Paris: Chez l’auteur, [1762?]](https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Marine-Militaire-title-page-L2002F55-660x1024.jpg)

Marine Militaire, ou Recueil des Differens Vaisseaux qui Servent à la Guerre

Nicolas-Marie Ozanne

Paris: Chez l’auteur, [1762?]The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

One of the most beautiful naval books of the period, Marine Militaire consists of fifty delicately engraved plates, with the text included on the plates rather than set separately in type. Twenty-one plates illustrate the different classes of French warships, from ships-of-the-line with more than one hundred guns to small bateaus. Twenty-five of the plates deal with naval tactics, ranging from boarding, the chase, defending and forcing passages and harbors, and bombarding ports.

“Cayer des Evolutions”

Antoine-Robert, vicomte du Cluzel

1777The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This painstakingly illustrated book of naval “evolutions,” or fleet maneuvers, reflects the careful study required to master the complex signals and sailing instructions used during the eighteenth century. Antoine-Robert, vicomte du Cluzel (1749-1795), was a twenty-eight-year-old lieutenant when he prepared these watercolor studies.

Etienne Marc Antoine Joseph, comte de Grasse-Limermont

Unidentified French artist

ca. 1792-1810The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2004

The senior officers of the French navy were known collectively as the Grand Corps. They were advanced exclusively from the gardes de la marine and gardes du pavillon<, training corps restricted to men of noble birth. Most of the senior naval officers of the American War of Independence were either Bretons or Provençaux. The latter included Admiral de Grasse and his kinsman Etienne, comte de Grasse-Limermont, chef d’escadre (1757-1838).![Click for a larger view. The Royal George: A First Rate Man of War Carrying 100 Brass Guns and 1000 Men, Supposed to be as Complete a Ship as the Sea Bears, [London, 1756?]](https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/The-Royal-George-PE-L2011F157f-1024x799.jpg)

The Royal George: A First Rate Man of War Carrying 100 Brass Guns and 1000 Men, Supposed to be as Complete a Ship as the Sea Bears

[London, 1756?]The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

HMS Royal George was the largest warship in the world and the pride of the Royal Navy when she was launched in 1756. She took part in the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in January 1780 and then sailed to the relief of Gibraltar. Her bottom was coppered later that year, increasing her speed and maneuverability. She sank in April 1782 while being heeled over for repairs, resulting in the drowning of over nine hundred people, including her commander.

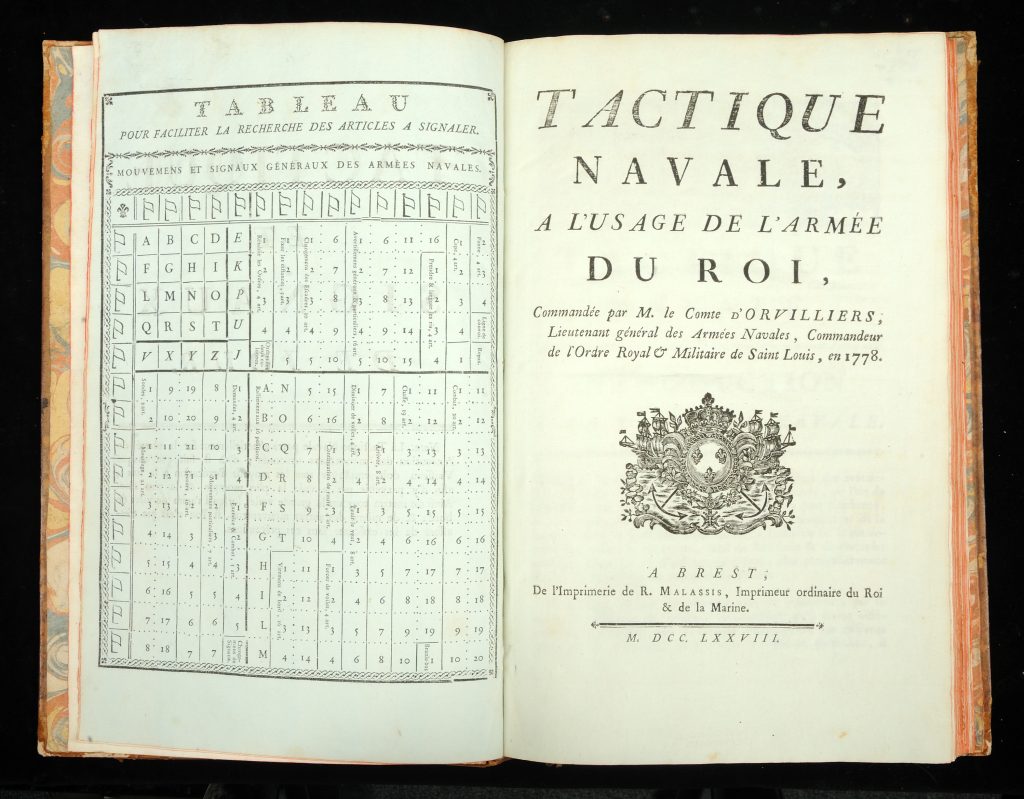

Tactique Navale a l’Usage de l’Armée du Roi, Commandée par M. le Comte d’Orvilliers, Lieutenant Général des Armées Navales

Jean-François du Cheyron, chevalier du Pavillon

Brest: De l’Imprimerie de R. Malassis, 1778The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Success in fleet engagements depended upon each commander recognizing and obeying orders conveyed by an elaborate system of signals. These signals, along with descriptions of the corresponding naval maneuvers, were distributed to captains before a fleet put to sea. Since the signal flags were raised in sight of the enemy, the descriptions were renumbered and the corresponding combinations of signal flags changed for each expedition to maintain secrecy.

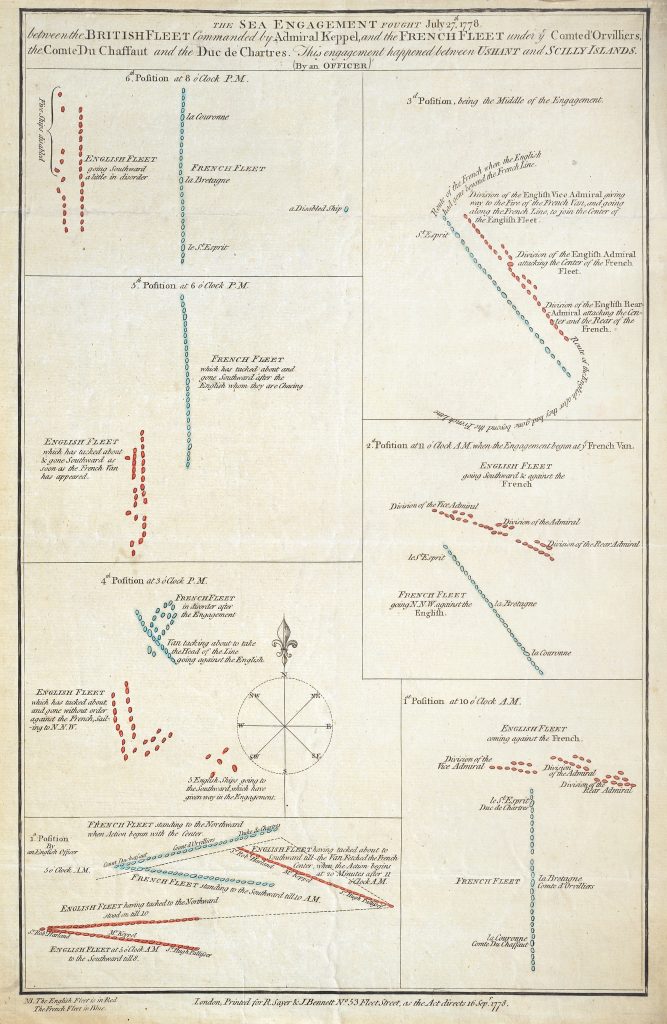

The Sea Engagement Fought July 27th, 1778, between the British Fleet Commanded by Admiral Keppel, and the French Fleet under ye Comte d’Orvilliers, the Comte DuChaffaut and the Duc de Chartres

“By an Officer”

London: Printed for R. Sayer & J. Bennett, September 16, 1778The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The Battle of Ushant, fought in the Channel, was the first major naval battle of the war. The battle ended in stalemate—a strategic victory for France, since Britain was forced to maintain a large part of its fleet in home waters as long as the French fleet was a threat to British dominance there. The failure of the British fleet to secure a victory led to months of recrimination. This contemporary chart of the battle was published at the height of the controversy.

Carte des Isles Antilles dans l’Amérique Septentrional, avec la Majeure Partie des Isles Lucayes, Faisant Partie du Théâtre de la Guerre entre les Anglais et les Américains

Louis Brion de la Tour

Paris: Chés Esnauts et Rapilly, 1782The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

French strategy called for concentrating naval forces in the Caribbean to seize Britain’s island colonies, including Jamaica, Barbados, Tobago, Saint Vincent, Grenada, Dominica, St. Kitts, Antigua and Nevis. With its resources stretched thin, the Royal Navy was unable to prevent the French from capturing Britain’s island colonies one after another. The French navy seized Dominica in 1778, St. Vincent and Grenada in 1779, Tobago in 1781 and St. Kitts, Nevis and Montserrat in early 1782. The French laid plans for the conquest of Barbados and Jamaica, but were unable to carry them out.

Model of HMS Roebuck

W. M. Brown

ca. 1834The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

HMS Roebuck, launched in 1774, was the prototype of an important class of twenty British warships. Roebuck-class warships carried forty-four guns on two gun decks, originally with twenty eighteen-pounders on the lower deck and twenty-two nine-pounders (later twelve-pounders) on the upper deck. Roebuck and her sister ships were well suited to operate in the rivers, inlets and shallow harbors of North America, where larger two-deckers could not go.

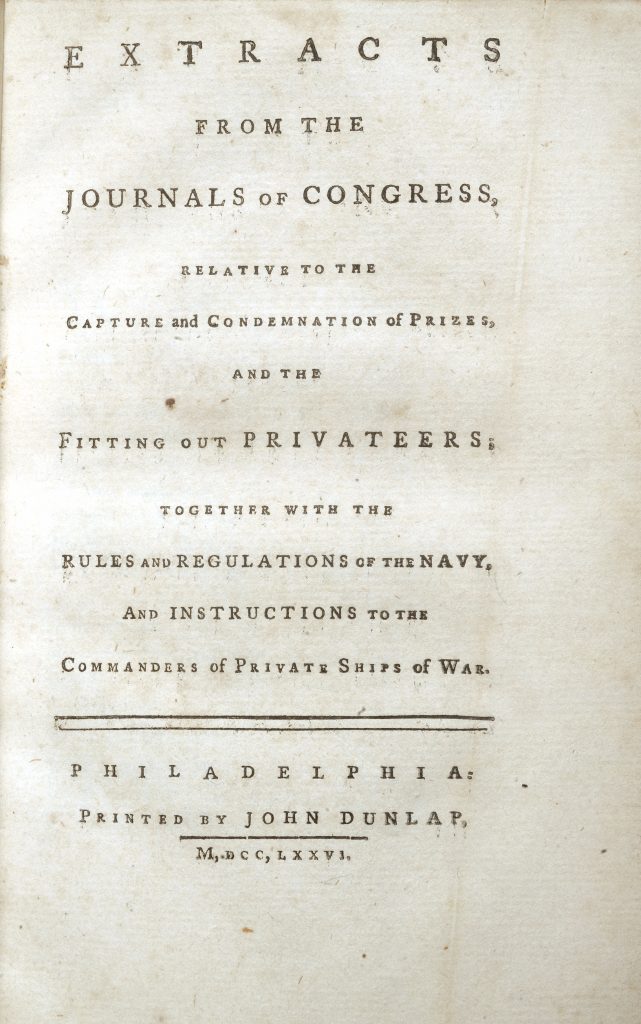

Extracts from the Journals of Congress, Relative to the Capture and Condemnation of Prizes, and the Fitting Out Privateers; together with the Rules and Regulations of the Navy, and Instructions to the Commanders of Private Ships of War

Philadelphia: Printed by John Dunlap, 1776The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Congress authorized privateers to operate against British shipping in a resolution of March 23, 1776. A few days later Congress made provision for issuing “letters of marque,” the formal licenses issued to privateers. This pamphlet includes the resolutions of Congress regulating privateers, published separately for the convenience of the hundreds of merchants and ship captains who conducted “private ships of war.”

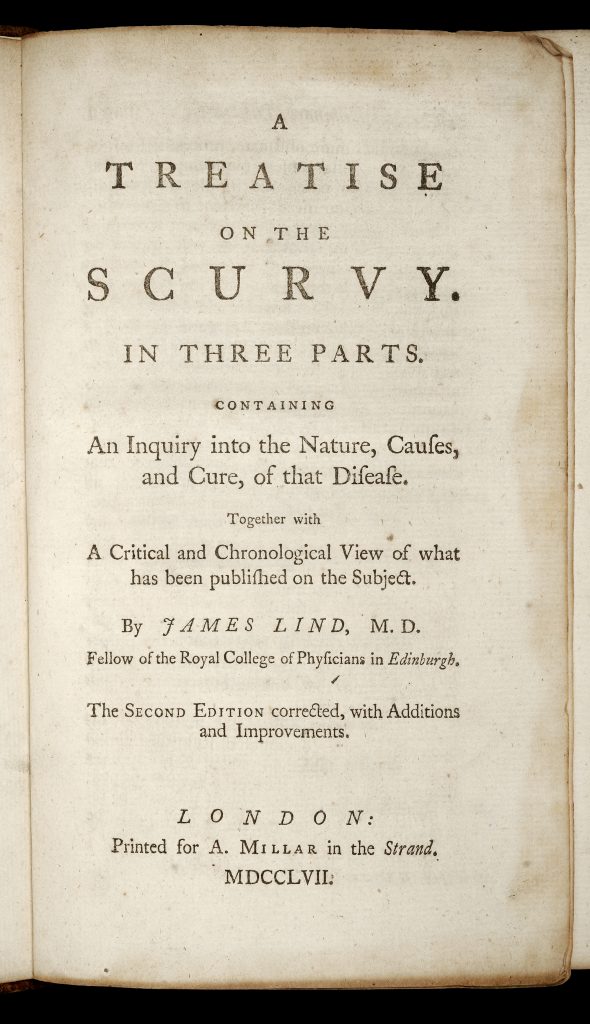

A Treatise on the Scurvy … Containing an Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease

James Lind

London: Printed for A. Millar, 1757The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Scurvy, a wasting disease caused by vitamin C deficiency, was common on ships more than a month or two at sea. The remedy remained a mystery until 1747, when Royal Navy physician James Lind (1716-1794) conducted clinical trials, treating one group of scurvy victims with cider, one with elixir of vitriol (diluted sulfuric acid), one with barley water and spices, one with seawater, and the last with two oranges and one lemon a day. The last group recovered. In 1753 Lind published his results in this book, recommending citrus juice as a preventive and treatment for scurvy. The British navy gradually adopted the practice, but scurvy plagued the French navy into the nineteenth century.

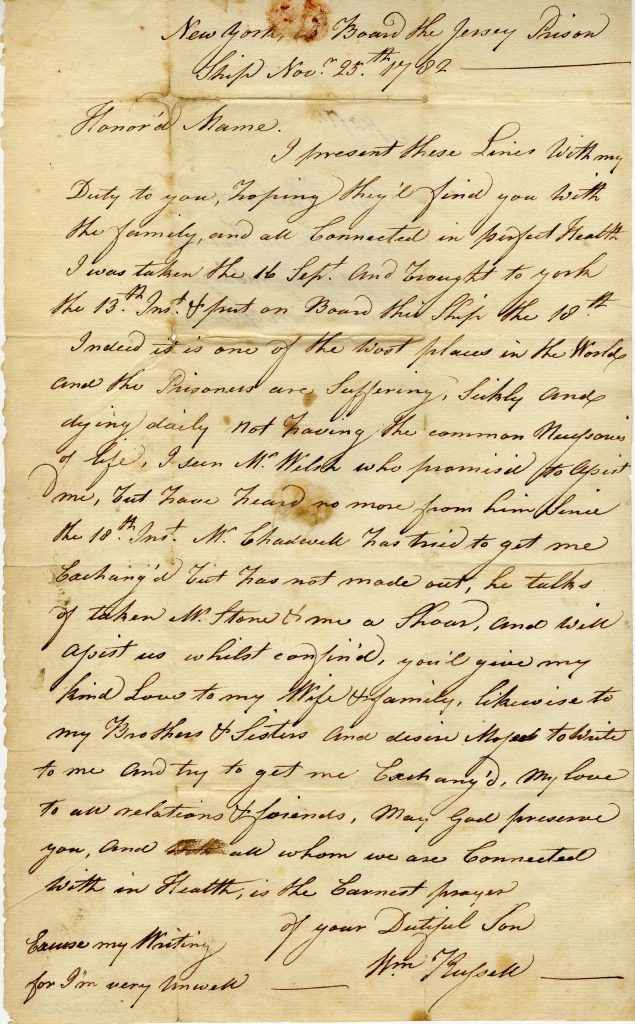

William Russell to Mary Richardson

“On Board the Jersey Prison Ship,” November 25, 1782The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Thousands of American merchant seamen, privateers and sailors were captured during the Revolutionary War. Many were imprisoned on rotting hulks moored in the East River, where as many as ten thousand may have died from disease, malnutrition and abuse. The author of this letter, William Russell (1748-1784), was imprisoned on the dreaded Jersey, moored near Brooklyn, from which he wrote to his mother. “I’m now in the worst of places,” he wrote, adding that food “is so scant that it is not enough to keep Soul and Body together.” Russell survived the ordeal, but died from tuberculosis shortly after the war.

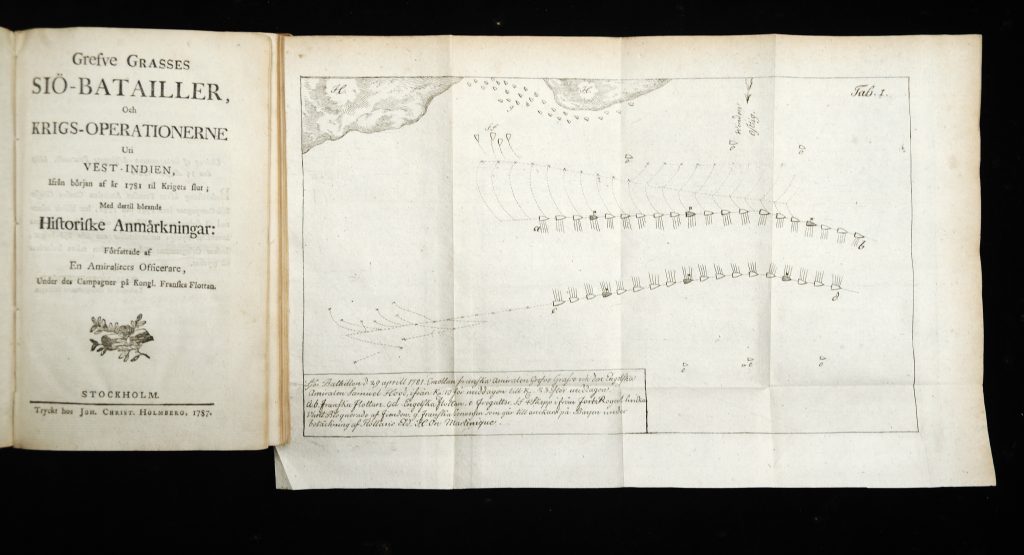

Grefve Grasses Siö-Batailler, och Krigs-Operationerne uti Vest-Indien

Carl Gustaf Tornquist

Stockholm: Tryckt hos Joh. Christ. Holmberg, 1787The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Carl Gustaf Tornquist (1757-1808), a young Swedish naval officer, volunteered for service in the French navy in 1778 and was appointed an enseigne de vaisseau. He served with Admiral de Grasse in 1781-1782 and the next year returned to Sweden, where he published this account—Comte de Grasse’s Naval Battles and War Operations in the West Indies—in 1787. This was the first extended published account of French operations under de Grasse, including the Battle of the Chesapeake.![Click for a larger view. Marine Royale de France Comparée a celle d’Angleterre … Juin 1782, Ministère de la Guerre, [Paris, 1782]](https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Marines-royales-de-France-MSS-L2001F350.1-1024x649.jpg)

Marine Royale de France Comparée a celle d’Angleterre … Juin 1782

Ministère de la Guerre

[Paris, 1782]The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Success and failure in the struggle for naval supremacy could be measured in the strength of the opposing fleets. This elegant French chart—documenting the warships of Britain and France—reflects how close to parity the two powers stood at the beginning of June 1782. The eighty-nine French vaisseaux de ligne are listed at far left. At far right are 104 British ships of the line. The predominance of the seventy-four-gun ship of the line in both fleets is apparent. Equally apparent is the enormous firepower of the opposing fleets, with 9,934 cannons on French warships and 13,974 cannons on British vessels, as well as the vast number of men required to man the opposing fleets: 109,755 French and 123,020 British sailors.

Society of the Cincinnati Eagle owned by Joshua Barney

Nicolas Jean Francastel and Claude Jean Autran Duval, Paris, France

January 1784The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of William Joshua Barney, Jr., Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1990

Joshua Barney (1759-1818) joined the Continental Navy in 1776. He served on successively larger ships, fought in dramatic ship-to-ship engagements, made his fortune as a privateer and cruised through much of the Atlantic world. He was captured repeatedly and escaped from an English prison disguised as a Royal Navy officer. He later commanded a converted merchantman in a desperate hand-to-hand battle with a larger British warship, which he boarded and captured. When the war ended, Barney was just twenty-four years old. He was an original member of the Maryland Society of the Cincinnati.