This lesson invites students to explore the rise of Francis Marion—the “Swamp Fox” of South Carolina—as a popular hero by examining two works of art: John Blake White’s painting General Marion Inviting a British Officer to Share his Meal (1836) and William Tylee Ranney’s painting Marion Crossing the Peede (1851). The goals of the lesson are for students to understand the importance of irregular forces like those Marion commanded to American victory in the Revolutionary War, and to understand how heroes are shaped in popular culture and the role such heroes play in shaping and defining American national identity.

The lesson asks students to treat the paintings as original sources from which we can discover how people of the past—beginning with the artists of the works under consideration—imagined the people and events depicted in the paintings. A premise of the lesson is that artists depict depict people and events to convey ideas about them that were relevant to their generation but which may not be clear to us.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle and High School

Recommended Time Frame

One +/- fifty-minute session

Objectives and Essential Questions

At the conclusion of the lesson, students will:

- understand the role of irregular troops in achieving victory in the Revolutionary War in the South;

- understand how the reputation of heroes is shaped by popular culture;

- understand how popular heroes contribute to national identity; and

- develop skills to assess historical image and documents critically,

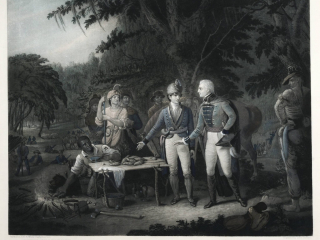

John Blake White’s General Marion Inviting a British Officer to Share his Meal (1836) was reproduced dozens of times and became one of the most familiar images of the American Revolution in the nineteenth century (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

Materials and Resources

Featured Resources

1. John Blake White, General Marion Inviting a British Officer to Share his Meal (1836)

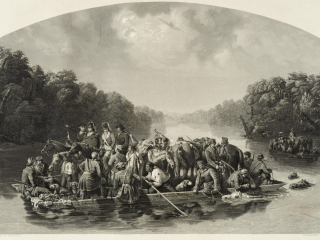

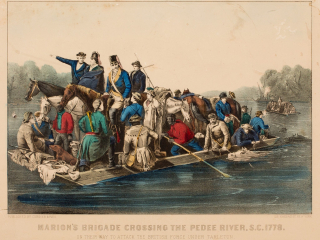

2. William Tylee Ranney, Marion Crossing the Peede (1851)

Related Images

4. Marion Crossing the Pee Dee, engraved by Charles Kennedy Burt, 1851

5. Marion and the British Officer at Dinner, engraved by Benson Lossing and William Barritt, 1858

6. Marion Crossing the Peedee, engraved by Benson Lossing and William Barritt, 1858

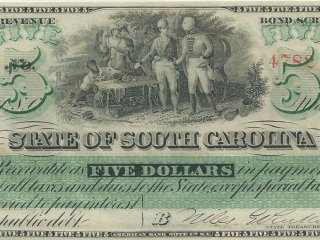

7. South Carolina $10 Revenue Bond Scrip (paper money), 1872

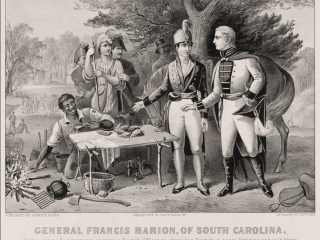

8. General Francis Marion, of South Carolina, lithograph by Currier & Ives, 1876

9. Marion’s Brigade Crossing the Pedee River, S.C. 1778, lithograph by Currier & Ives, 1876

Related Document [for the Extension]

10. The Pension Application of Samuel Weaver

Background Knowledge

Victory in the American Revolution was won by creating, supplying, and maintaining a regular army capable of contending with the British army in the open field and through the assistance of France, which supplied arms and ammunition Americans could not manufacture and the regular troops and naval forces that ultimately brought the war to a successful conclusion. Irregular troops, consisting mostly of militia and short-term volunteers, as well as mounted units of the Continental Army, contributed to the American victory by harassing British soldiers in camp and on the march, by attacking British supply lines and foraging parties, and by attacking loyalist troops and loyalist civilians, preventing them from supporting the British army.

Irregular troops played a major role in defending the interior of South Carolina and North Carolina in the later stages of the Revolution. The British army and navy captured Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1780, forcing the surrender of the Continental Army defending the state. British troop then marched into the interior to complete the conquest of South Carolina and routed a hastily assembled army of Continental troops and militia at Camden, South Carolina, on August 16, 1780. For several months thereafter, irregular troops and militia units were the only American forces available to contest British control of the South Carolina interior. They were never numerous enough to fight the British army in a major battle, but they were able to prevent the British from taking stable control of the state using hit-and-run tactics.

Francis Marion (1732-1795) was one of the most successful American leaders in this irregular kind of war. Marion was a planter. He had fought in of the French and Indian War and served in the defense of Charleston in 1776 and as a lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army at the Siege of Savannah in 1779. He was with the army in Charleston in 1780, but had gone home to recover from a badly broken ankle and so was not captured when the army surrendered. He immediately organized an armed band to contest British control of the South Carolina interior — mainly the area north of Charleston, between the city and the North Carolina border. A low-lying region divided by sluggish rivers and swamps, it provided ample hiding places and proved idea for the guerilla tactics Marion employed. His band usually numbered between twenty and seventy men, and at times increased to a hundred or more, most of whom supplied their own arms and horses.

In September 1780, Marion routed a body of loyalist troops at Black Mingo Swamp, northwest of Georgetown. British General Cornwallis,commanding the British army, sent a force under Col. Banastre Tarleton to capture or kill Marion in November. After pursuing Marion and his men through the swamps for many miles, Tarleton gave up, complaining that as for that “damned old fox, the Devil himself could not catch him.” The name stuck, and Marion was known thereafter as the “Swamp Fox.” The governor of South Carolina, who had withdrawn to North Carolina, appointed Marion a brigadier general of South Carolina state troops. During the winter of 1780-1781 Marion made his camp at Snow’s Island on the Pee Dee River, in an area of swamps that favored men with local knowledge. From this base Marion rode out to harass British troops, attack loyalists, and prevent the British from gaining control of northeastern South Carolina. When Continental troops under Nathanael Greene returned to South Carolina in 1781, Marion cooperated with Greene to force the British to retreat to Charleston. After the war Marion returned to his plantation and rebuilt his house, which had been burned by the British during the war. He died there in 1795.

William Tylee Ranney’s Marion Crossing the Peede (1851) reflects the popular image of Marion and his men in the middle decades of the nineteenth century (Amon Carter Museum of American Art).

Sequence and Procedure

- Explain to the class who Francis Marion was and what he accomplished. Marion and his men were genuine heroes of who played an important part in winning the Revolutionary War. Marion’s reputation in the nineteenth century exceeded that importance. After George Washington, Francis Marion was probably the best known leader of the Revolutionary War to nineteenth century Americans. Marion was remembered as the chief hero of the Revolutionary War in the South, eclipsing Nathanael Greene as well as other South Carolina leaders, including Thomas Sumter, who excelled at the same kind of irregular warfare as Marion. We should honor and respect Marion and his men for what they did. We should also work to understand how the reputations of popular heroes develop over time. Examining how Americans imagined Francis Marion offers us a good chance to do that.

- Introduce Mason Locke Weems’ Life of Francis Marion to the class. Marion’s status as a popular hero owes much to this biography by Mason Locke Weems, first published in 1805. Like Weems’ Life of George Washington—the source of the story of Washington and cherry tree—Weems’ Life of Francis Marion was written in an easy-to-read style that appealed to ordinary people. It went through dozens of editions and was one of the most popular American books of the early nineteenth century. An anecdote in book describes the visit of a British officer to Marion’s camp to negotiate a prisoner exchange. According to Weems, Marion offered to share his simple dinner of roasted sweet potatoes and water with his guest. The British officer was surprised that Marion lived so simply. “’Why, sir,’ Marion replied, ‘the heart is all; and when that is once interested, a man can do any thing. . . . I am in love; and my sweetheart is LIBERTY.’ When he returned to his own camp, the officer told his commander: ‘I have seen an American general and his officers, without pay, and almost without clothes, living on roots, and drinking water—and all for LIBERTY! What chance have we against such men!’”

- Introduce the painting General Marion Inviting a British Officer to Share his Meal by John Blake White (1781-1859), a native of South Carolina. White finished the painting in 1836. The painting is a depiction of the scene described by Weems. To draw the class into a discussion interpreting the painting, ask the following:

- Why do you think the artist chose this story from Weems’ book to depict in his painting? Why, for example, didn’t he depict Marion in battle instead? What does he want us to think about Francis Marion and his men?

- What legendary character does this depiction of Francis Marion remind you of? [The answer we’re looking for is Robin Hood. If no one suggests him, try drawing the answer out with follow up questions.] Think of a legendary outlaw who lives with his band in the forest . . .

- In fact, one of the most popular books in the United States in the 1820s and 1830s was Ivanhoe, a novel by the British writer Sir Walter Scott. Robin Hood is a major character in Ivanhoe. He fights the tyrant king with hit-and-run tactics until a just government is restored. In the book, Robin Hood is generous and kind as well as a skilled warrior at home with the rough ordinary men in his band. The artist probably intended us to think of Francis Marion as someone like Robin Hood. He even portrayed Marion wearing green and brown, like the traditional image of Robin Hood.

- In 1831, a writer named William Cullen Bryant published a poem titled “The Song of Marion’s Men.” Bryant imagined Marion as a modern Robin Hood, leading a band of merry men in the woodlands and swampy rivers of lowland South Carolina:Our band is few, but true and tried,

Our leader frank and bold;

The British soldier trembles

When Marion’s name is told.

Our fortress is the good greenwood,

Our tent the cypress tree;

We know the forest round us,

As seamen know the sea. - Can a painting like this one influence many people? [The obvious answer is that a painting can only influence people who see it.] How can a picture like this reach more people? In fact, thousands of prints of this painting were make in 1840, and it was reproduced from that print many in many ways.

- Introduce the printed versions of the image, explaining that the first one, from 1841, was fairly expensive and was probably only owned by people who had money to spend decorating their homes with patriotic scenes. But the same image was adapted for books and magazines, like the print from Harper’s Weekly Magazine, which isn’t exactly like the painting but conveys the same idea. Many thousands of copies of the Currier and Ives lithograph were printed and sold for a dollar or less. Patriotic prints like this were common decorations in late nineteenth- century homes. White’s depiction of Marion and the British officer was so famous that South Carolina even put it on paper money issued by the state.

- Introduce the second painting, Marion Crossing the Peede by William Tylee Ranney, but instead of working through an interpretation as a class, break the class up into groups to consider some interpretive questions after providing the class with the basic background: William Tylee Ranney (1813-1857) painted this “Swamp Fox” surrounded by his men crossing a lowland river. He titled the painting Marion Crossing the Peede, misspelling the name of the Pee Dee River. Marion’s base in the winter of 1780-1781 was on Snow’s Island on the Pee Dee River. Ask each group to discuss the following questions]

Assessment and Demonstration of Student Learning

- Introduce the second painting, Marion Crossing the Peede by William Tylee Ranney, but instead of working through an interpretation as a class, break the class up into groups to consider some interpretive questions after providing the class with the basic background: William Tylee Ranney (1813-1857) painted this “Swamp Fox” surrounded by his men crossing a lowland river. He titled the painting Marion Crossing the Peede, misspelling the name of the Pee Dee River. Marion’s base in the winter of 1780-1781 was on Snow’s Island on the Pee Dee River. Ask each group to discuss the following questions:

-

- The title of Marion Crossing the Peede is similar to the title of what famous painting of a Revolutionary War scene? [Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze (pronounced Loy-za), which was first exhibited in the United States in the fall of 1851, a few months after Ranney completed Marion Crossing the Peede]

- Do you think William Ranney was influenced by that painting, or the other way around, or do you think the similarities between the two paintings are a coincidence? [The answer is we don’t know. Leutze painted Washington Crossing the Delaware in Germany and brought it to American shortly after Ranney finished his painting, but the fact that Leutze was painting Washington Crossing the Delaware was being discussed in the art community in New York City, in which Ranney was an active participant. He might have been inspired by Leutze’s theme to come up with a similar painting without having seen Leutze’s work.]

- How are the two paintings similar?

- How is Marion Crossing the Peede different than Washington Crossing the Delaware, and what do you think those differences mean about how Ranney intended to present Francis Marion and his men?

- Which of the figures in the Marion Crossing the Peede is Francis Marion? Why do you think so? [ The casual viewer is likely to assume Francis Marion is the officer mounted on a black horse. Marion is actually the mounted officer wrapped in a brown cloak—the epaulet, which indicates Marion’s rank as a general, gives him away. This was a clever visual tribute to Marion’s ability to disguise his plans and hide from his enemies.]

- Referring to the later versions of the image, explain how Marion Crossing the Peede became widely known

Extension

In this exercise, the class get to act in the place of the Pension Office and decide whether a man who claimed to be a veteran who served with Francis Marion should be given a mention for his service. Distribute the following statement and review it with the class:

The Pension Application of Samuel Weaver

One of the thousands of people who applied for a pension under the Pension Act of 1832 was an elderly man named Samuel Weaver. In 1836 he presented himself to the county court in Laurel County, Kentucky. He reported that he was born in Cumberland County, Virginia, in 1755, but had moved to Surry County, North Carolina, where he was called up for militia service in the spring of 1780. His militia unit marched to the relief of Charleston, but Weaver explained that he was detached to guard baggage before reaching the city and thus avoided capture when Charleston surrendered on May 12, 1780. He returned home, but immediately volunteered for a second three-month tour and was marched from Hillsborough, North Carolina, to join Francis Marion.

Weaver claimed that during his service “he saw General Washington and General Francis Marion,” and that he once remembered other colonels and generals but confessed that “his memory is almost gone.” Weaver was over eighty years old when he gave this statement, and was describing events of 1780-1781 that had taken place as much fifty-six years earlier. When the Pension Office reviewed this first statement, it decided not to give Weaver a pension.

Weaver returned to the court in November 1839 to renew his application, providing more details about his service in the hope that the Pension Office would change its mind. In his second statement, Weaver provided details of his service guarding baggage outside of Charleston during the siege. He added to his account of his second three month’s service by explaining that he volunteered as a substitute for his father, who had been drafted, and told the clerk how his unit had wound up joining Marion, “he does not now where but thinks it was on the Pedee River or some of its waters.” It was in the context of this account that Weaver told this story. Note that the statement is written in the third person, because it was written down by a court clerk. Weaver was unable to sign his name to the statement, which indicates that he could neither read nor write. He made an S on the document in place of a signature. Here is what he said:

During the time he was with Genl. Marion, a British officer as he was told came into camp, but for what he does not know, he was roasting & baking sweet potatoes on the coles – Genl. Marion stepped up with the British officer and remarked he believed he would take up Breakfast, he felt proud of the request, puled out his potatoes, wiped the ashes off with a dirty handkerchief, placed them on a pine log (which was all the provision they had) and Genl. Marion and the British officer partook of them. He has been told by some that this has been recorded in the life of the Genl. as dinner but this was a breakfast.

After reviewing the statement, divide the class into two or more groups, and ask them to gather in different parts of the classroom to discuss Weaver’s application and decide whether he should be given a pension. The decision rests on whether the students believe Weaver is telling the truth or not. Each group should discuss this question and record the factors suggesting that Weaver is telling the truth, and those suggesting he may be making up his story to secure a pension. Each group should vote one way or the other, and when the class reconvenes as a group, a spokesman should tell the class what factors led the group to its conclusion. The factors in favor of Weaver and those against should written down on a smart board or blackboard. The teacher, acting as Commissioner of Pensions, can render a decision, or the class can vote on whether Weaver gets his pension. This is an exercise in assessing historical evidence.

The first set of factors weighing against Weaver include his age, his admission that “his memory is almost gone,” and the long time between his alleged service and his testimony. Most of the students should see this, and this offers an opportunity to make an important point. Weaver’s pension application is primary source evidence, but not all primary source evidence carries the same weight. The Revolutionary War had been over for fifty-six years when Weaver gave his statement in 1839. That’s a long time to remember details.

Another factor weighing against Weaver is his claim to have seen George Washington during his service. Except for the Siege of Yorktown, Virginia, Washington was in New England and the middle states throughout the Revolutionary War. Weaver does not report serving anywhere Washington served during the war, so Weaver’s claim to have seen Washington is almost certainly false. Whether it is an outright lie or simply an old man’s hazy, mistaken memory is more than we know.

The chief thing we are looking for students to be skeptical about is Weaver’s claim to have been present (and indeed to have served) the sweet potato meal to Marion and the British officer. Weaver says the meal was breakfast rather than dinner, which is an interesting twist. But doesn’t it seem likely, or at least possible, that Weaver had heard the story as it was reported in Weems’ Life of Francis Marion and decided to say he was involved in the scene?

On the other side of the question, the Surry County, North Carolina, militia did serve in the Siege of Charleston and avoided capture when the American army surrendered, so that part of Weaver’s statement might be true. The issue really comes down to whether the students believe his version of the sweet potato story. Since Weaver couldn’t read, which is indicated by his signing the statement with the letter S (many illiterate people made an X), he couldn’t have read the story in Mason Locke Weems’ biography of Francis Marion. Nor could Weaver have seen the White painting or any print of it. Note that the earliest print (the expensive one) wasn’t printed until 1841, two years after Weaver made his statement. Weaver said that he had heard about the version of the story in Weems’ book. Would a man who couldn’t read be likely to appropriate a story from a book?

The Pension Office granted Samuel Weaver a pension of twenty dollars a year for his Revolutionary War service, crediting him for six months’ service in the North Carolina militia. The surviving pension documents don’t say whether the Pension Office staff believed his story about Marion and the sweet potatoes or thought it was an old man’s tall tale.

Revolutionary Achievements Categories

Independence, National Identity

Exploring the Revolution Categories

Revolutionary War, The Legacy of the Revolution