It’s not every man who can play Everyman, but Joseph Plumb Martin pulled it off with what looks like effortless ease. His Narrative of some of the Adventures, Dangers and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier is one of the most insightful, passionate and carefully crafted first-hand accounts of the Revolutionary War—and the most successful. You can hardly pick up a book about the Revolutionary War written in the last forty years without bumping into Joseph Plumb Martin. He’s the most quotable, and most quoted, common soldier of the Revolution. But he’s more than that, and more interesting.

Martin’s Narrative was rescued from over a century of obscurity by George Scheer, a frequent contributor to American Heritage magazine, who discovered a copy of the first and only edition of the book, published in 1830, in the library of Morristown National Historical Park. He transcribed it, added an introduction and gave it to the world as Private Yankee Doodle, published by Little, Brown in 1962. It took off, appealing to patriots and cynics in equal measure, and has never gone out of print.

The book has been packaged and repackaged under titles including The Diary of Joseph Plumb Martin, A Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier and Ordinary Courage. Paperback versions are commonly assigned in college courses. Selections from the Narrative appear in anthologies on the Revolution and on the experience of war, including one assembled by John McCain. A version for children is available as A Young Patriot: The American Revolution as Experienced by One Boy and another as Yankee Doodle Boy. Martin has shown up in the PBS series Liberty’s Kids. Passages of the Narrative enrich documentaries. His name rolls by in the credits of nearly every miniseries and feature film on the Revolutionary War. The National Park Service named the hiking trail circling Valley Forge the Joseph Plumb Martin Trail. He’s become one of our best-known revolutionaries. He’s everywhere.

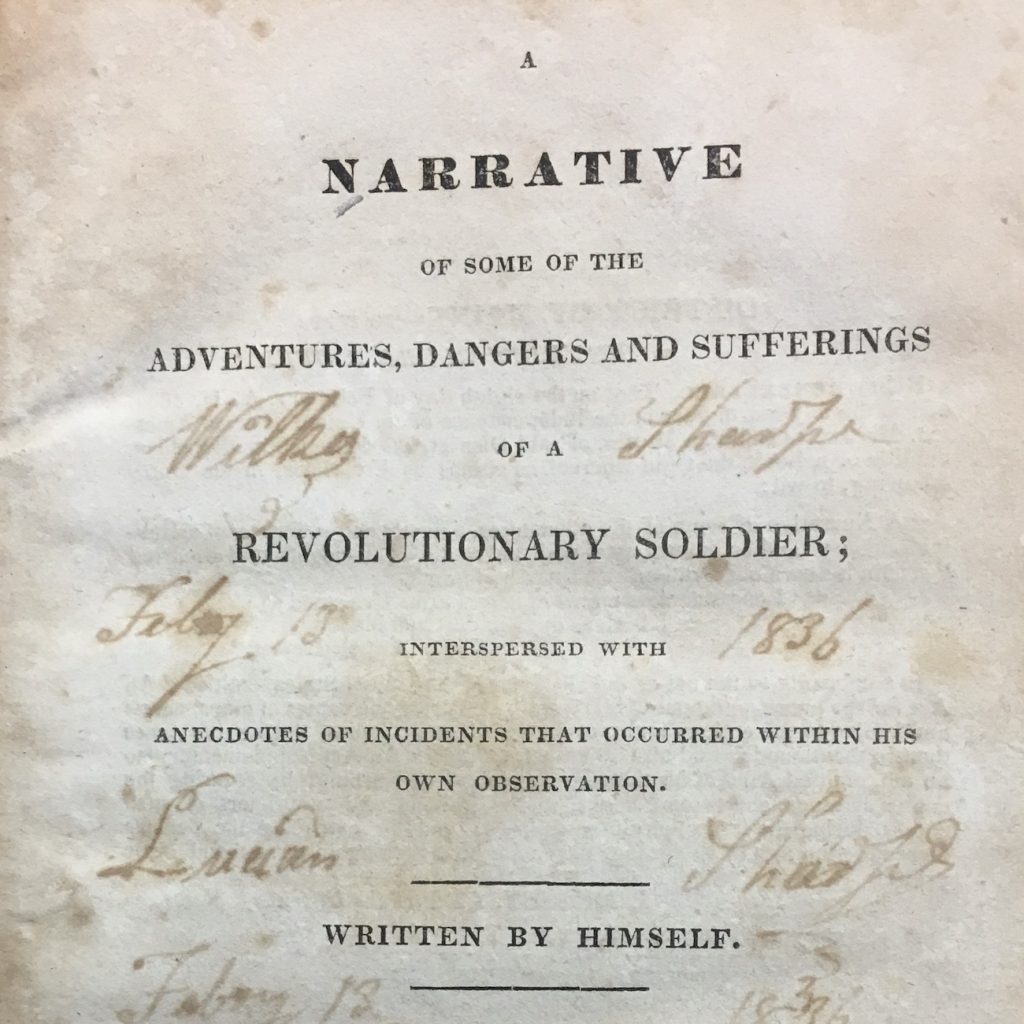

Given the book’s history, its modern popularity is a surprise. Martin was a seventy-year-old veteran when his account of nearly eight years in Washington’s army was published by Franklin Glazier in Hallowell, Maine, a town on the Kennebec just below Augusta. Glazier printed almanacs, sermons, schoolbooks, statutes, law reports and a little church music. Martin’s Narrative was an outlier, and it seems unlikely that Glazier printed more than a few hundred copies. Martin explained that he wrote the book to satisfy his friends and did not expect it to “reach beyond the pale of my own neighborhood.” Surviving copies are rare, and the fact that George Scheer stumbled onto one in the late 1950s is remarkable.

It was not the first autobiographical narrative of a common soldier, but it is an early one. Memoirs of generals were common fare in Britain from the late seventeenth century, as were moralizing tracts and fantastic tales retailed as the work of ordinary soldiers, but genuine accounts of military service written by enlisted men and junior officers were something new in the early nineteenth century, made possible by the declining cost of printing and improvements in book marketing that made it practical, if not very profitable, for little printers like Glazier to publish them.

Martin was born in Massachusetts in 1760 and raised by his maternal grandparents in Connecticut. The family valued education—his father, the Reverend Ebenezer Martin, had graduated from Yale. Joseph’s youth was interrupted by the Revolutionary War and he never attended college. He joined the Connecticut militia in 1776 and served in the defense of New York City. Discharged at the end of 1776, he enlisted as a private in the Connecticut Continental Line in April 1777 and served for the duration of the war. He was assigned to the light infantry in 1778 and promoted to corporal, and in 1780 he was transferred to the new Corps of Sappers and Miners and promoted to sergeant. He fought in several of the major engagements, including Brooklyn, Kip’s Bay, Harlem Heights, White Plains, Germantown, Fort Mifflin, Monmouth and Yorktown, and was among the last Continental soldiers discharged in 1783.

More than forty years passed before Martin began writing his narrative of the war. It’s an old man’s book, based on memories filtered through decades of ordinary struggles and striving, successes and disappointments. Yet it’s often a young man’s voice we hear when we read it, which suggests a clever old man did the writing. The narrator is contrived for effect—not a fiction, but not quite the author himself.

That the narrator is an invention is signaled by Martin’s insistence that the book consists of nothing but “the common transactions of one of the lowest in station in an army, a private soldier.” In truth, Martin wasn’t a private for long. His assignment to the light infantry placed him among the army’s elite troops, and his quick promotion to corporal and later sergeant suggests that he stood out, despite his youth. Literate in an army filled with barely literate soldiers, he must also have been industrious and reliable. The son of a Yale-trained minister, he probably read in his spare time and wrote letters home.

He wants us to imagine young Private Martin as just another one of the boys. “I never studied grammar an hour in my life,” he says, “when I should have been doing that, I was forced to be studying the rules and articles of war”—the strained “forced to be studying” has the deliberate, country-rube cadence of an invention like Huck Finn or Brer Rabbit.

He drops the Everyman pose to tell us in his own voice: “I never learned the rules of punctuation farther than just to assist in fixing a comma to the British depredations in the state of New York; a semicolon in New Jersey; a colon in Pennsylvania, and a final period in Virginia,” ending with “a note of interrogation, why we were made to suffer so much in so good and just a cause.” A man who invents puns about punctuation was probably never one of the boys.

Martin’s alter ego is a somewhat roguish fellow, a joker and a trickster, whose place near the bottom of the social scale provides him with a perspective on the seedier side of the Revolution. He really sees history from the bottom up, a vantage point from which hypocrisy, deceit, greed and corruption are in plain view. The rest of us see what’s happening above. He sees what’s really happening from below, a not-so-innocent young man adrift in an war filled with chicanery, selfish opportunism, abused authority and hopeless bumbling.

His Narrative is a tale of needless suffering and exploitation. “Almost every one has heard of the soldiers of the Revolution being tracked by the blood of their feet on the frozen ground,” he wrote. “This is literally true; and the thousandth part of their sufferings has not, nor ever will be told.” Americans had the means to support the war, he says, but too many of them were content to let others do the fighting while they raked in the spoils, from petty swindlers taking advantage of hungry soldiers, to embezzlers, cheats and war profiteers. Continental officers, he complained, were too often cruel, vindictive and unfeeling.

Enlisted men had won the war, yet in the end they had been “turned adrift like old worn-out horses.” For decades veterans were disappointed by the government’s unfulfilled promises of land grants, back pay and compensation for the collapse of the Continental dollar. “The country was rigorous in exacting my compliance to my engagements,” Martin wrote, “but equally careless in performing her contracts with me; and why so? One reason was, because she had all the power in her hands, and I had none. Such things ought not to be.”

Much of the modern popularity of Martin’s Narrative lies in his raw critique of the selfishness and vice he witnessed. Yet for all his cynicism and frustration, he was a patriot who confessed he felt “a secret pride swell my heart” at Yorktown, “when I saw the ‘star-spangled banner’ waving majestically in the very faces of our implacable adversaries.”

Few men wrote about our Revolutionary War with such unsentimental clarity or condemned its corruption and failures more bluntly. Yet he was amazed that men “starved and naked, and suffering every thing short of death . . . should be able to persevere through an eight years’ war, and come off conquerers at last!” The Revolution, for all its vices, astonished him. It should astonish us, too.