On the evening of December 18, 1829, a young Philadelphia portrait painter named John Neagle set off on foot toward the home of an artist friend named Thomas Birch. It was snowing and the streets of Philadelphia must have been nearly empty. People who had somewhere to go pulled their coats tight and hurried through the dark.

The thirty-three year-old Neagle had not gone far when he saw an old man huddled under a makeshift shelter, trying to keep out of the snow. Neagle might have kept on walking, but he paused. “I found him much benumbed with cold and scantily clad,” Neagle wrote in his diary. “His outer dress was ragged—His flannel and coat scarcely covered his naked body and he had an apology for a shirt—all were in rags and strings.”

Neagle tried to engage the man in conversation, but found that his first language was German, which Neagle did not speak. Rather than give up in frustration, Neagle invited the old man to come home with him, where the artist “administered to his wants over a good cheerful fire.” It might have been the first kindness anyone had shown the old man in a long time. Neagle went out to ask his neighborhood grocer, a German, to come translate for him.

There by the fireside the artist learned that the man’s name was Joseph Winter. He was something like seventy-three years old, though Winter wasn’t quite sure of his own age. He had come to Pennsylvania before the Revolution and settled in a German community near Bethlehem, where he had worked as a weaver. He had been married, but his wife and children were long dead. His eyesight had grown dim and his fingers were no longer fit for the loom. Unable to support himself, he had become, Neagle wrote, “a lone wanderer in a world evincing but little feeling or sympathy for him.”

Neagle learned something else that made a profound impression on him. As a young man, Winter had served in the Revolutionary War, and “had fought very hard to establish the liberties of our country.” Winter was a homeless veteran. Indeed he is the first homeless veteran about whom we know anything at all. Homeless veterans are now a familiar sight in our cities, but they were something new and appallingly sad in 1829, at least to a thoughtful man like John Neagle, whose imagination quickly turned to how he might express that sadness and inspire his fellow Americans.

A few years earlier he had completed a masterpiece—a heroic portrait of an ironmaster titled Pat Lyon at the Forge. Lyon commissioned the portrait, writing to Neagle “that I do not desire to be represented in this picture as a gentleman—to which character I have no pretensions. I want you to paint me at work at my anvil, with my sleeves rolled up and a leather apron on.” The painting created a sensation when it was exhibited. It was revolutionary in its realism—a craftsman’s portrait in his working clothes, standing at an anvil—and densely symbolic—beneath his leather apron Lyon wears a pair of fine shoes no blacksmith ever wore to work, and outside the open window is the Walnut Street Jail, where Lyon had once been imprisoned for a crime he did not commit.

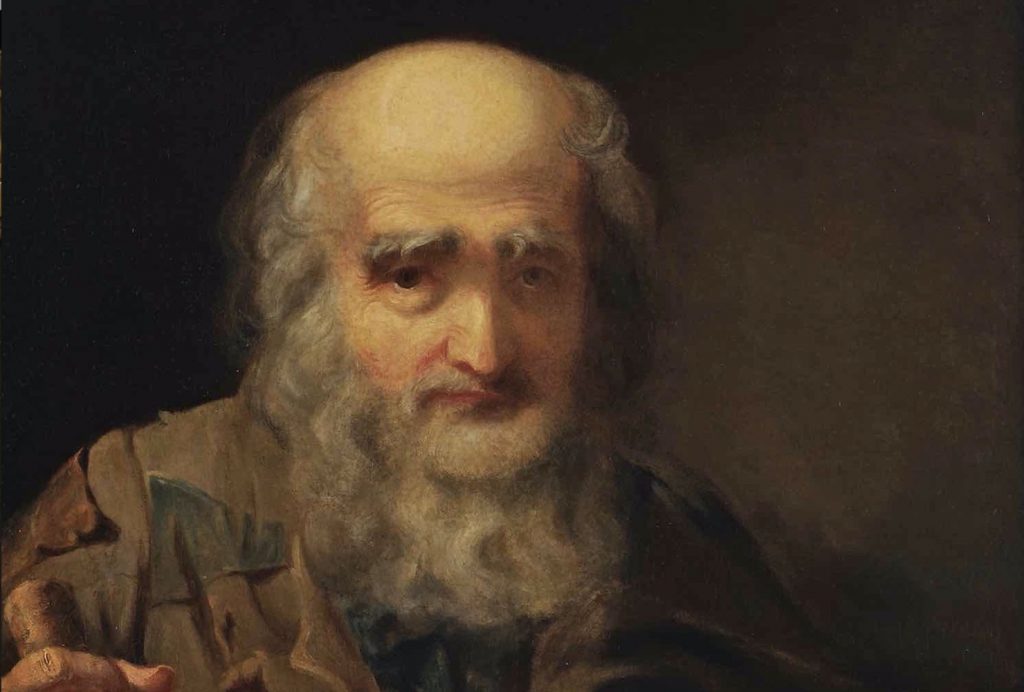

Looking at the homeless Joseph Winter, Neagle decided on a project as richly symbolic as Pat Lyon at the Forge. He would paint Winter’s portrait, just as he appeared—old, his face etched in sorrow, exhausted, his clothes shabby and threadbare. Winter sat for the portrait, which is the first known portrait of a homeless veteran.

The finished portrait attracted wide public notice, and Neagle had it engraved for sale with the title Patriotism and Age. The portrait made Winter a symbol of the thousands of elderly veterans of the Revolutionary War for whom the nation had made no provision. “This picture speaks a satire of melancholy truth,” one viewer commented, “that must reach the heart of every American, who is not forgetful of the blessings inherited from his forefathers.” Nearly a quarter of a million Americans had borne arms in the Revolutionary War, and tens of thousands were still living in 1829. Most of them were then in their seventies or eighties. Like Joseph Winter, many were no longer able to support themselves, and depended on family or charity to meet their most basic needs.

The federal government had not turned its back entirely on veterans of the Revolution. Those who had been disabled were granted pensions during the war, and in 1818 Congress had voted to provide pensions to veterans of the Continental Army and Navy who could document their service and prove their financial need. But the law made no provision for the majority of Revolutionary War veterans, who had served in the militia, and pension examiners rejected thousands of applications on the grounds of insufficient evidence of service or of financial distress. Joseph Winter did not receive a pension under the act of 1818.

We don’t know how Winter came to live on the streets of Philadelphia. We can guess that he left his home near Bethlehem when he was no longer able to work as a weaver and made his way to Philadelphia because in the city he might find some way to support himself. Perhaps he was attracted to the city because he might find food there, or inexpensive lodging, or access to public or private charity, or simply because a city is a better place to beg than a country town—all reasons the homeless are drawn to cities today. The decision cut him adrift from the people he knew and the community in which he had lived, making him, as Neagle saw, a “lone wanderer.”

For John Neagle, the homeless veteran he took into his home was a challenge and a chastisement—a symbol of our unrealized aspirations as well as our ingratitude. We turn too easily from both. Neagle reminds us to look harder, and to look beyond material needs—beyond the food and shelter Joseph Winter so clearly lacked, to the indefinite needs we all have for the conditions necessary to be happy.

That might sound like a thing very difficult to define, but our Revolution placed it among our highest aspirations. Our right to life, and therefore a claim on what we need to survive, is a right so fundamental that our Declaration of Independence calls it a self-evident truth. So, too, is liberty, a right to be free from unnecessary restraints—a fundamental right but hard to define in a comprehensive and immutable way, since the restraints necessary to maintain civil society change with society itself. Jefferson might have stopped with life and liberty—conditions clearly necessary to human flourishing—but he forged on to name, but not to define, a right to pursue happiness.

Our fundamental right to pursue happiness is a right to fulfill needs that governments cannot fulfill—among them our needs for dignity, respect, appreciation, honor, fellowship, community and love. We do not need these things to live or to be free, but we need them to flourish—to be happy. Governments cannot provide them. Jefferson knew this, which is why he wrote that we have a right to pursue happiness rather than a right to happiness itself. The role of government is only to create and defend the circumstances in which free people can pursue happiness in their own way.

The soldiers of our Revolution, and all of our veterans since, risked their lives and deferred enjoyment of their liberties to create and defend the circumstances essential for our freedom and happiness. Their sacrifices transcend the conditions of any normal employment, and oblige all of us as beneficiaries to express our respect and appreciation—to care, in Lincoln’s words, “for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves.”

On that snowy December night 190 years ago, John Neagle met a homeless veteran who was cold and hungry. He took him home and “administered” to his most basic needs. But when he painted Winter’s portrait he treated the old soldier with dignity, respect, appreciation and honor. He called on his contemporaries to treat all of the surviving soldiers of our Revolution in that way, and through his art he calls on us to treat our own veterans—particularly those who have become lonely wanderers in a world so often without sympathy—with that dignity, respect, appreciation and honor we owe to them, and which are vital to their happiness.

In 1832, moved in part by the popular sensation caused by the engraving of Winter’s portrait, Congress passed a comprehensive pension act, offering pensions to every surviving veteran of the Revolutionary War, without regard to disability, financial need or whether he was in the Continental service or the militia. Shortly thereafter, Congress extended those same benefits to the widows of Revolutionary War veterans.

Joseph Winter disappeared from the historical record after his encounter with Neagle. The weather warmed over Christmas that year, and Winter may have returned to the streets, or found lodgings in the city with Neagle’s help or the help of new-found friends. We cannot know. We can only hope that his last years were contented ones.