Introduction

Prior to the formal creation of the United States the spirit of that union lived in a man whom Americans had rallied around for more than a generation. He instilled stability amid revolution, and after independence was achieved, he embodied America’s potential to become a nation founded on civic virtue and republican ideals. This lesson in the Imagining the Revolution series asks students to consider how eighteenth-century artists portrayed America’s champion, George Washington.

Key images to be considered are:

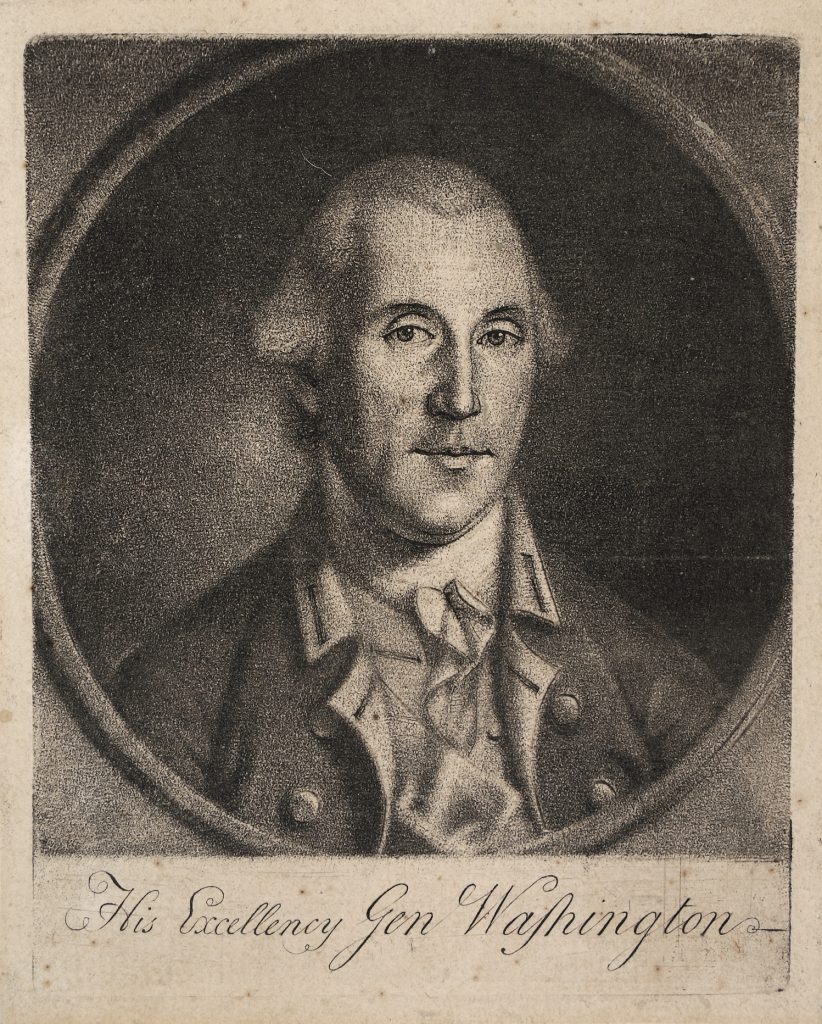

- Charles Willson Peale’s 1778 mezzotint, His Excellency Gen Washington, the first published engraving of Washington executed by an artist who had seen Washington;

- Charles Willson Peale’s 1779 full-length portrait, George Washington at the Battle of Princeton; and

- Gilbert Stuart’s 1796 full-length portrait of Washington as president painted for the marquis of Lansdowne, since known as the Lansdowne portrait.

Although a reluctant portrait-sitter, Washington sat for both Charles Willson Peale and Gilbert Stuart on multiple occasions, and was painted by Peale in seven life portraits over the course of twenty-three years. Of Peale, who created Washington’s very first portrait in 1772, Washington remarked “I fancy the skill of this Gentleman’s Pencil . . . in describing to the World the manner of the man I am.” Gilbert Stuart’s ability to capture Washington on canvas drew similar praise—according to aficionado John Neal: “If George Washington should appear on earth, just as he sat to Stuart, I am sure that he would be treated as an impostor, when compared with Stuart’s likeness of him.”

The goal of this lesson is to encourage students to explore how the work of these artists went beyond simply introducing the world to America’s Cincinnatus, George Washington—ultimately these images helped forge America’s national identity.

Imagining General Washington

In June 1775 amid escalating tensions with Great Britain, the Second Continental Congress of America’s thirteen colonies appointed fellow delegate and military veteran George Washington commander-in-chief of its Continental Army. As the conflict progressed into war and American support for its developing Revolution ebbed and flowed, public endorsement of their commander in the field—and the demand for images bearing his likeness—steadily grew, resulting in the production of images on both sides of the Atlantic by artists who neither personally met with Washington nor consulted preexisting authentic portraits or sketches.

One such example, appearing in England in 1775, was a mezzotint entitled George Washington, Esqr. General and Commander in Chief of the Continental Army in America. Printed below the image was a note from the engraver: “Done from an Original Drawn from Life by Alexr. Campbell, of Williamsburgh in Virginia.” George Washington’s comment upon receiving a copy of the engraving, for which he claimed never to have posed, was that “Mr. Campbell—whom I never saw—has made a very formidable figure of the Commander-in-Chief, giving him a sufficient portion of Terror in his Countenance.”

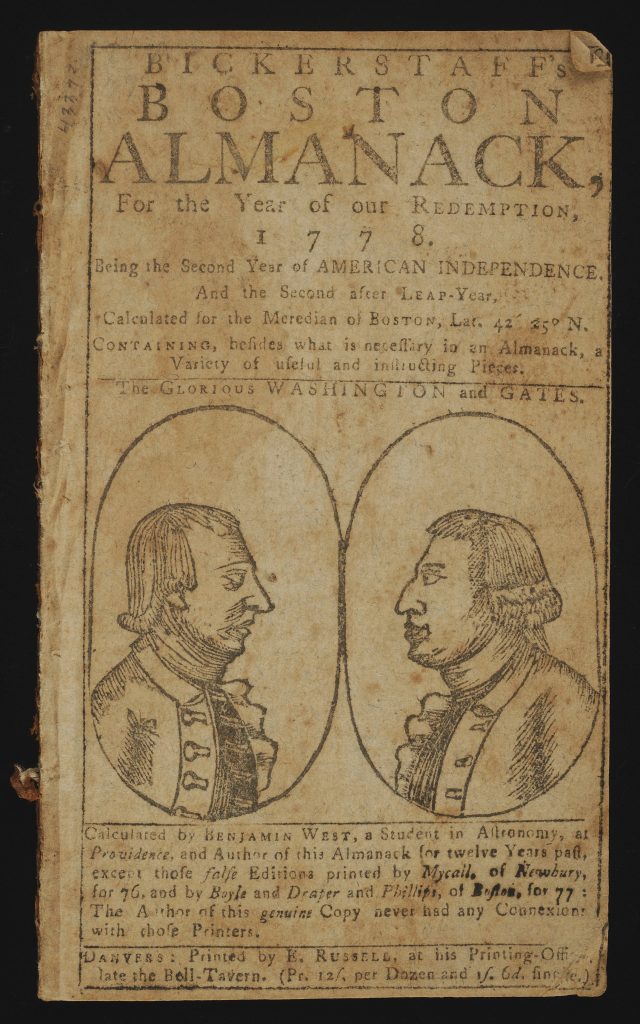

In Boston, another early engraving entitled “The Glorious Washington” appeared in 1777 opposite that of General Horatio Gates in Bickerstaff’s Almanack. Although she may have seen similar images in print, it is unlikely that local poet Phillis Wheatley would have been moved by a primitive work such as this to pen her inspired 1775 poem, His Excellency General Washington:

Fam’d for thy valour, for thy virtues more, Hear every tongue thy guardian aid implore! . . . A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine, With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! Be thine.

The dour face on the Almanack’s cover likewise bears no resemblance to the vision of Washington conjured by the words of Abigail Adams writing to husband John after meeting the General in Cambridge in June 1775: “I was struck with General Washington. You had prepaired me to entertain a favorable opinion of him, but I thought the one half was not told me. Dignity with ease, and complacency, the Gentleman and Soldier look agreably blended in him. Modesty marks every line and feture of his face. Those lines of Dryden instantly occurd to me ‘Mark his Majestick fabrick! He’s a temple Sacred by birth, and built by hands divine His Souls the Deity that lodges there. Nor is the pile unworthy of the God.’”

Charles Willson Peale’s His Excellency Gen Washington

While the release of additional unstudied portraits of George Washington would have likely met public demand, in 1778 Charles Willson Peale unveiled an engraving drawn from life entitled His Excellency Gen Washington. Peale had previously painted the earliest known life portrait of Washington in 1772 to record Washington’s service as a Colonel in the Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War, but that image was not released to a general audience. In His Excellency, the crisply uniformed Washington wears the hint of a smile, suggesting his confidence in the future of American sovereignty—a future that was anything but certain in 1776 when the two men sat together as artist and subject. The engraving radiated the Washington magnetism French colonel Robert Guillaume Dillon would later describe in his 1781 memoir as “a form which beguiles as one looks at it, his great character and his soul apparent in his features; I recognized without difficulty the General out of a thousand officers of the army, he was one of the most handsome men that I’ve seen in my life.” Other artists replicated Peale’s engraving in print so frequently that even crude variations became recognizable as George Washington. With His Excellency and his next illustration of the general, Washington at Princeton, Peale, as both an artist and an outspoken patriot, helped shape America’s emerging national spirit, as well as document its growing veneration for George Washington.

Charles Willson Peale’s Washington at Princeton

After serving in the Pennsylvania militia at the Battle of Princeton with General Washington, Charles Willson Peale composed his third portrait of the general in 1779. More detailed and richly symbolic than his earlier works, Washington at Princeton portrays a triumphant George Washington in repose after his first battlefield victory, with fallen British and Hessian flags at his feet. An orderly escort of a line of prisoners in the background pays homage to traditions of European warfare adopted by Washington’s American forces. General Washington’s blue sash and epaulets signify that by his superior rank he could have directed the maneuvers at Princeton from a protected location. Peale, however, painted clearing smoke over Washington’s left shoulder where his headquarters flag stands unfurled and one of his men calms his horse—prompting the portrait’s audience to correctly infer that the general himself had led the American line during the battle’s critical charge. Washington’s composure, leaning jauntily on a bronze cannon with his hat off and legs crossed, affirms his comfort on the field of battle, and his gaze and sure expression, paired with a blue sky intensifying over his right shoulder, providentially forecast the success of American independence. The painting was immediately heralded as a visual embodiment of the Revolution’s noble cause, and replicas of Washington at Princeton were in demand before Peale finished the original commission for the Supreme Executive Council of Philadelphia. Copies of Washington at Princeton introduced America’s charismatic wartime hero to a world-wide audience and served both to legitimize the American rebellion and to present America—represented by its commanding general—as an emergent global force.

With Washington at Princeton, Charles Willson Peale embraced the sophisticated conventions of Europe’s painting masters to showcase an American commander in an American victory. Peale’s perspective, as well as the perspective of the eighteenth century audience, had been carefully groomed by the work of contemporary artists recording military accomplishment on the world’s stage, such as Antoine Pesne with Frederick II, King of Prussia. Commissioned in 1747 as a gift for Frederick’s uncle George II of England, Pesne’s portrait celebrated the tradition of the European warrior-king, presenting its subject clad in armor beneath an ermine-trimmed robe adorned with crowns. A mighty sword at his side and a plumed helmet at his feet romantically invoke Frederick’s connection to a bygone age of knights and chivalry. In his right hand he holds the spyglass used to coordinate the battle from afar, and with his left hand he gestures toward the horizon to invite his portrait’s admirers to witness the advance of his army, his empire, and his legacy as Frederick the Great.

Benjamin West, the American-born painter to the royal court of George III of England, enjoyed retelling the story of a conversation he had with King George during the American Revolution. When the king asked what General Washington would do if America prevailed, West said he thought Washington would return to his farm. ‘If he does that,’ the king is supposed to have remarked, ‘he will be the greatest man in the world.’ True to form, after American independence was won, General Washington fulfilled West’s prophesy, declaring to Congress: “Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theater of Action; and bidding an Affectionate farewell to this August body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my Commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.”

When Imagining General Washington, students should consider the following questions:

- Why were Americans, and others abroad, fascinated by images of George Washington?

- What values and ideas about George Washington, military leadership, and revolutionary America do these images suggest to their audiences?

- What imagery do the words of Phillis Wheatley, Abigail Adams and Robert Guillaume Dillon invoke, and how does that vision compare to these early images of General George Washington?

- How is the composition of Antoine Pesne’s Frederick II, King of Prussia similar to Charles Willson Peale’s Washington at Princeton? What details indicate that Frederick the Great was a conquering soldier-king, and that George Washington was the commander of a citizen army fighting for its independence?

- What values and ideas are conveyed about America and its military in portraits of American generals serving after George Washington?

Imagining President Washington

Despite George Washington’s best efforts, public retirement proved elusive. After a period of post-Revolution faltering, America again called upon him—initially to help craft a stronger republican government, but ultimately to serve another eight years as the first president of the United States.

Gilbert Stuart’s George Washington

Washington’s transformation from war hero to unanimously elected leader of the world’s newest democracy was preserved for posterity in a portrait by Benjamin West’s American protégé, Gilbert Stuart. Formally entitled George Washington, this painting, a gift for the first marquis of Lansdowne, is commonly referred to as the Lansdowne portrait. By its very commission—for a member of the British gentry—this work was created for display in a gallery of traditional aristocratic portraiture, in the company of peers of equivalent authority and status. With George Washington, Stuart masterfully holds true to the style and composition expected by a portrait of a formal head of state, yet he infuses his work with cues that indicate the sovereign he is presenting is neither the king of America nor an autocratic dictator. While the sheathed sword in his left hand alludes to his military past and to his presidential power as commander-in-chief, President Washington wears a distinguished yet decidedly un-militaristic, common black suit. Washington’s right hand is extended to replicate the posture he adopted to deliver his annual address to Congress and to echo the sculpted poses of the democratic hero-statesmen of ancient Greece and Rome. The portrait is full of references to classical republican government juxtaposed with symbols of the new American republic, like the carved leg of Washington’s desk featuring eagles perched atop the capital of a fasces-like column, against which leans a bound volume titled Constitution & Laws of the United States. In a nod to Washington’s scrupulous devotion to duty and stewardship, Stuart has rooted other books to the base of the painting, among them American Revolution and General Orders. Upon Washington’s desk next to his quill and presidential papers sit two more titles, The Journal of Congress and The Federalist. A marble pillar authoritatively anchors the president in the tableau, and a clearing sky accented by a rainbow suggest a covenant between the Almighty and the United States—and perhaps the consecration of George Washington, who had announced he would not seek or serve a third term. Gilbert Stuart continued to paint George Washington in a series of iconic portraits, each leading to a demand for copies and keeping Stuart busy and well-paid for years. One of his commissioned replicas of the Lansdowne portrait has been among the master works on display at the White House since 1800, perhaps serving to remind subsequent presidents to likewise temper their ambitions.

Although remarkably similar in composition, George Washington’s noble civilian deportment in the Lansdowne portrait is lavishly upstaged by his Revolutionary ally in 1779’s Portrait of King Louis XVI by artist Antoine-Francois Callet. In Callet’s painting, His Most Christian Majesty is wrapped in the imperial regalia befitting the Sun King’s eighteenth-century heir—Louis is swathed in satin, silk, and a robe of velvet brocade fleur-de-lis and ermine—and in the spirit of ‘l’état c’est moi’ (I am the state) he looks directly at his portrait’s audience. Louis holds an ornate walking stick in one hand and extends a lavishly plumed hat in the other, subtly revealing a golden sword at his side. To his right is a solid pillar planted with a gilded foundation, and to his left is a throne embellished with the figure of Iustitia, the allegorical personification of moral justice, holding her famous scales beneath a looming fasces. Although Lady Justice would be obscured were he to sit down, the universally recognized ax and rod symbolizing power over life and death would remain clearly visible on the king’s right. Absent is any other iconography that might serve to check Louis’ power or remind the monarch of the British American colonies’ Declaration on the acts of “absolute Despotism” committed by their own sovereign.

By 1797 George Washington’s personal renunciation of power stunned Europeans as well as fellow Americans a second time. Despite his immense popularity, Washington insisted that the office of the president of the United States be protected from any appearance of autocracy. Invoking the spirit of Roman general Cincinnatus, who served the republic of Rome for two periods of crisis then returned to his life as a farmer, Washington returned to his plow at Mount Vernon. Just four years earlier, Louis XVI also stepped out of the public theater—forcibly removed from his throne, then beheaded by guillotine at the Place de la Révolution.

Like the models of civic virtue immortalized by classical literature he admired, George Washington was celebrated in verse. English poet Lord Byron penned several odes about Washington and lionized Washington’s legacy in a sardonic poem dedicated to the famous ambition of Napoléon Bonaparte:

There was a day—there was an hour,

When that immeasurable power

Had been an act of purer fameBut thou forsooth must be a king,

And don the purple vest

As if that foolish robe could wring

Remembrance from thy breast.

Vain froward child of empire!Where may the wearied eye repose

When gazing on the Great;

Where neither guilty glory glows,

Nor despicable state?

Yes–one–the first–the last–the best: The Cincinnatus of the West

Whom envy dared not hate,

Bequeath’d the name of Washington

While Byron’s 1814 Ode to Napoléon Buonoparte eloquently captured Napoléon’s metamorphosis from republican defender to imperial dictator in verse, it was mastered visually by artist Francois Gerard’s Napoléon Emperor of France, which appeared in 1805 and unseated popular images portraying Bonaparte as the soldier-hero of the French Republic. Although Napoléon publicly heralded Cincinnatus of the West George Washington as “dear to all freemen” and a “great man [who] fought against tyranny [and] established the liberty of his country,” Bonaparte chose to follow the controversial trajectory of his own classical idol, Julius Caesar. During his second exile, Emperor Napoléon I conceded “they wanted me to be another Washington.” For Napoléon, curtailing his legacy to suit the bounds of republican propriety was—as it is for us today—as alien an idea as Imagining Emperor Washington.

When Imagining President Washington, students should consider the following questions:

- What values and ideas about George Washington and the American republic in 1796 are presented by the Lansdowne portrait, and which of those values and ideas continue to represent America today?

- How is Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait of George Washington similar to the paintings of Louis XVI and Napoléon Bonaparte?

- What values and ideas were the artists of King Louis XVI and Napoléon Emperor of France trying to convey about the governance of France in 1779 and 1805 when they were painted, and which of those values and ideas continue to represent France today?

- What values and ideas about America and the presidency are conveyed by the official portraits of American presidents serving after George Washington?