On the night of March 5, 1770—251 years ago tonight—a party of British soldiers shot and killed five Bostonians in an event known ever since as the Boston Massacre. The killings shook the loyalty of Britain’s North American colonists to the British government. John Adams wrote that the “foundation of American independence was laid” that night.

The basic outline of what happened is well established, although the fine details are elusive. The soldiers who participated in the killings were tried for murder, and dozens of eyewitness accounts were entered into evidence at their trials. The accounts differ considerably and in some cases conflict with one another. The massacre occurred on the dark streets of an eighteenth-century city in late winter. It began with an altercation between a Bostonian and a sentry outside the customs house. Angry words were spoken, a crowd gathered, the sentry called for assistance, and a captain and six soldiers armed with loaded muskets came to his aid. The crowd grew—whether to thirty or forty or two hundred or even more is unclear—and ugly words turned to threats and taunts and then to sticks, snowballs and chunks of ice thrown at the soldiers. The captain ordered the crowd to disperse, to no effect. As the situation degenerated, one of the soldiers fired, and quickly the others joined him. Eleven civilians were shot. Three died on the scene and two others died within a few days.

These are basic facts, and they are not in dispute. But how these facts are presented in our history classrooms—and particularly the interpretative context into which they are now woven—illustrates the challenges we face in reviving understanding and appreciation of the American Revolution. For generations the Boston Massacre was presented to students as Exhibit A in the case for resistance and rebellion. The British government was so intent on imposing its will on the colonies that it sent an army of occupation to Boston, and its soldiers shot and killed unarmed civilians who confronted them.

Over the last generation, this interpretation of the Boston Massacre has been dismantled. At first this flowed from a reasonable effort to encourage students to look at events from different points of view. The sentry was obviously frightened, and so were the soldiers who came to his aid. The Bostonians in the crowd weren’t carrying placards—they were cursing the soldiers and throwing things at them. The soldiers were young men. They weren’t seasoned veterans. It was dark and they were scared the mob was going to kill them. They acted in self-defense.

These, too, are facts, and facts are stubborn things. There are two sides to the story. But today’s students aren’t likely to get both sides. The version of the Boston Massacre widely taught today could be called neo-loyalist. It takes the basic outline and embeds it in an interpretation that presents the victims as participants in a mob that got what it had coming—when the taunts turned to threats and protestors began throwing things, what did they expect? People got shot. It was inevitable. Of course it was all very unfortunate (we can hear the king’s ministers saying that in London), but that’s what happens when mobs challenge armed soldiers.

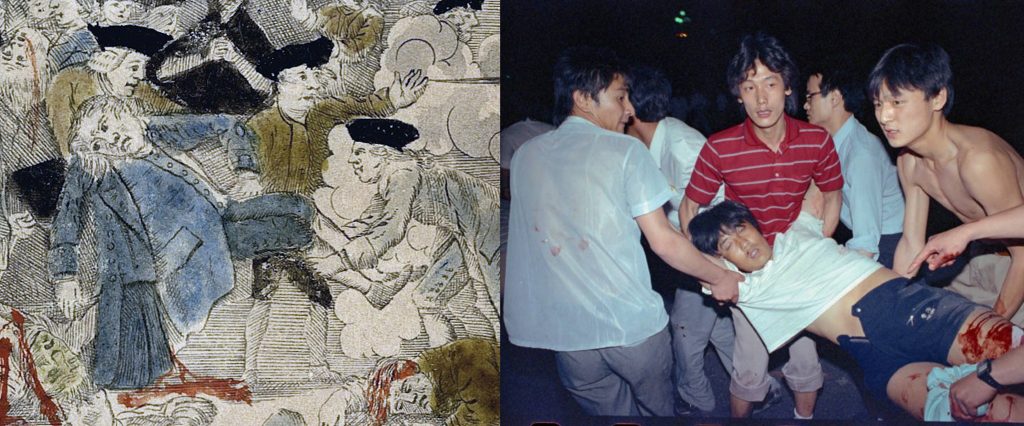

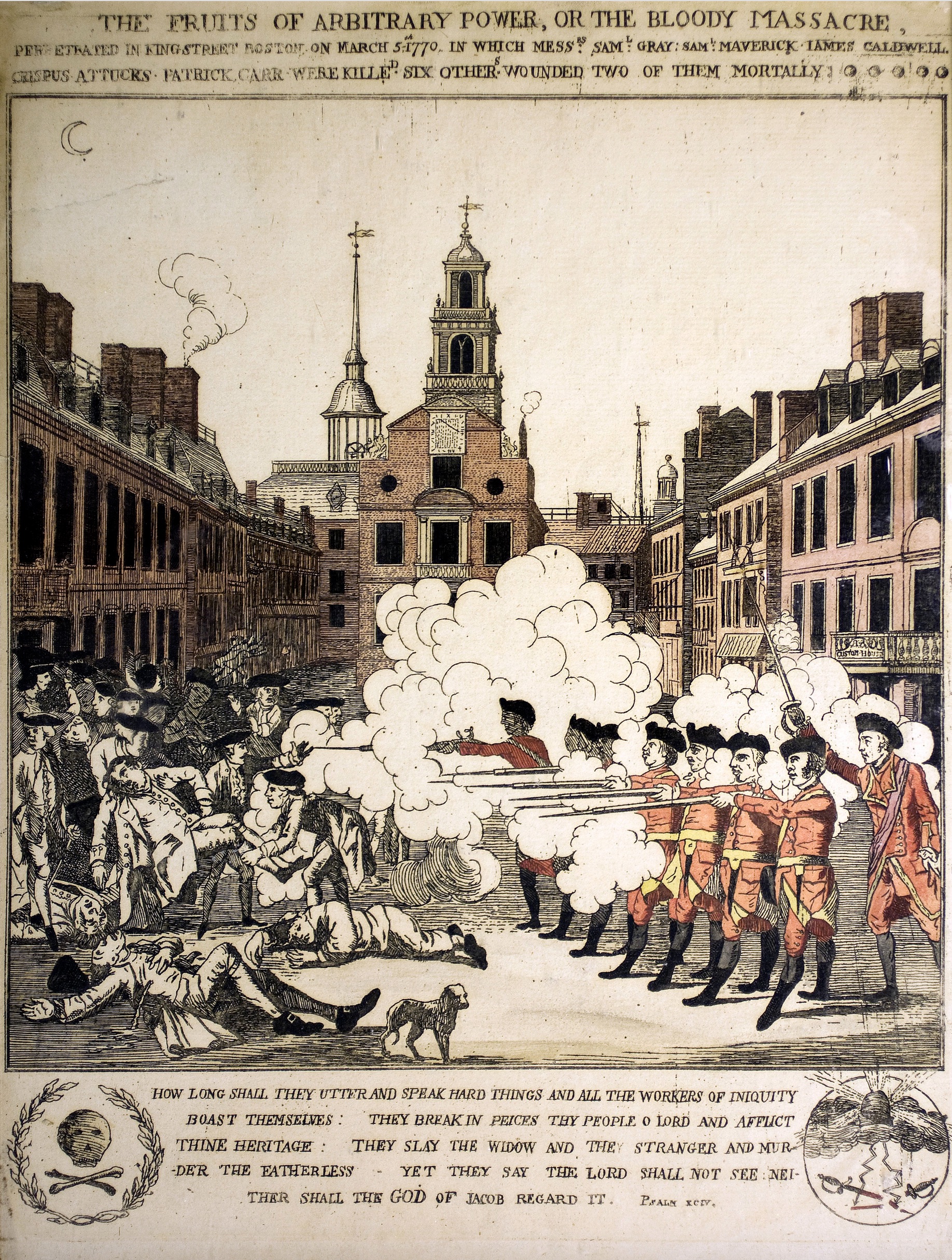

Henry Pelham’s The Fruits of Arbitrary Power includes a passage from the 94th Psalm—an enduring challenge to tyranny: “How long shall the wicked triumph? How long shall they utter and speak hard things? and all the workers of iniquity boast themselves?” (American Antiquarian Society).

Exhibit A in the case for the neo-loyalist version of the unfortunate events of March 5, 1770, is the Paul Revere engraving, The Bloody Massacre in King Street, Boston. Published and republished in history books for two hundred years, it’s the best known contemporary image of an event in the American Revolution. Today’s students are commonly taught that the print is pure propaganda, depicting innocent Bostonians being gunned down by evil soldiers. Nor was what happened in Boston, the neo-loyalists say, a “massacre.” Like the print, the use of the word here is pure propaganda, they say, attached to a street brawl by radical leaders like Samuel Adams to whip the colonists into a frenzy of irrational hatred of the British—who were, after all, just trying to bring order to the empire.

Let’s set aside, for a moment, the horrors perpetrated in the name of bringing order to empires. For reasons that defy rationality, the empathy today’s students are taught to feel for people under colonial rule does not extend to the king’s subjects in the thirteen colonies in North America.

There are, indeed, some things about the Revere engraving to criticize. To begin with, Revere appropriated—by our standards he stole—his view of the massacre from Henry Pelham, the young half-brother of artist John Singleton Copley, who drew the scene with the intention of producing an engraving for sale. Pelham apparently didn’t know how to prepare an engraving plate. He probably went to Revere, who was a pretty poor artist but knew how to engrave, seeking technical advice. Revere had possession of Pelham’s design for a few days and decided to copy it and issue an engraving of his own, which he did. He beat Pelham to the market with his pirated engraving, and thus the most famous view of the event is credited improperly to Revere.

Revere wasn’t the first person to call the killings a massacre, and it really was a massacre, despite what our young people may be taught. Eleven gunshot victims, three left dead at the scene and two more mortally wounded, doesn’t make a massacre—or so says the new orthodoxy. But consider this. The population of Boston in 1770 was about 15,000, so about one in 3,000 Bostonians was killed on March 5, 1770. The population of modern Washington, D.C., is about 700,000. If one in 3,000 Washingtonians was suddenly killed by an army of occupation in a single incident, the death toll would be over 200 people. Wouldn’t that be a massacre, especially if the people killed were not bearing arms?

Murder at Sharpeville, by Godfrey Rubens, depicts the aftermath of a 1960 massacre of unarmed civilians in South Africa. The suffering and loss it expresses echoes the suffering and loss in Boston and a hundred other places where soldiers have turned on unarmed civilians (Consulate of South Africa, London).

Of course it would be. For all of their apparent inaccuracies, the Revere and Pelham engravings speak to the horror of armed soldiers killing unarmed civilians. We have seen it happen too many times in the 251 years since that night—in encounters between our army and the Indians, in Europe under the Nazis, in Soviet Russia, at My Lai and Kent State, and in the horrifying genocides of our own time—in massacres so appalling that what happened in Boston so long ago has lost the power it once had to disturb us as deeply as it should. Yet the scenes are often much the same—Revere’s King Street is Tiananmen Square in miniature, his dead are eerily like the crumpled bodies in Godfrey Rubens’ painting of the victims of the Sharpeville Massacre in South Africa.

Henry Pelham wisely titled his engraving The Fruits of Arbitrary Power. By fruits he meant consequences—the results of British policy. Today the word arbitrary is often used to mean random, unpredictable or erratic. In the eighteenth century it meant ungoverned or uncontrolled. Arbitrary power is uncontrolled power.

There was nothing random or unpredictable about what had happened. In 1768 the British had landed four regiments, each of some seven hundred men—that’s one soldier for every six civilians—to occupy and impose their government’s arbitrary will on Boston. The warships that brought them entered the harbor with their gun ports open, and the occupying army entered the city with bayonets fixed in a naked display of arbitrary power. Before the massacre the force was reduced to two regiments, but Boston remained a city under armed occupation. The killings in Boston, Pelham reminds us, were entirely predictable—the natural consequences, or fruits, of a government exercising uncontrolled power over its people.

The Boston Massacre still has much to teach us. It revealed how far the British might go to impose their will. The American Revolution, we should teach our children, was about controlling the power of the state, limiting it and making government always the servant of the people and an instrument of justice, not a tool for tyrants to impose their will on others. The massacre was a warning in the night, and it will remain a warning of dangers our world has yet to master.

Above: The desperate effort of Bostonians to carry a wounded man to safety in 1770, depicted here by Paul Revere, was repeated in Tiananmen Square in 1989—and many times in between.