Among the most curious treasures in the library of the American Revolution Institute is a monochrome aquatint with etching of a properly dressed gentleman with his left hand gripping the pommel of his sword and his right arm draped around a bare-breasted woman whose arm is curled suggestively around his neck. The legend reads The Hero returned from Boston. The publication line reads “London. Printed for Thos. Hart, as Act directs, 7th Sepr. 1776.” The print is excruciatingly rare. Besides our imprint, there is one in the Yale University Art Gallery.

Our effort to understand the print leads down peculiar byways of the eighteenth-century print business. The name of the publisher, Thomas Hart, is associated with a series of fictitious portraits of American leaders, including George Washington (including one on horseback and one on foot), John Hancock, Israel Putnam, David Wooster, Horatio Gates, Charles Lee, Esek Hopkins, Benedict Arnold, John Sullivan, and John Paul Jones, dated between 1775 and 1779. These prints, all of which are mezzotints, are attributed to publishers Thomas Hart, C. Shepherd, and John Morris.

None of these prints bears any real resemblance to its subject, despite the publishers’ effort to persuade customers that they were authentic likenesses. The print of Hancock, the legend says, was based on a portrait by an artist named Littleford, though no artist named Littleford is otherwise associated with Hancock. The legends on the prints of Washington claims they were based on a portrait “Drawn from the life by Alexr. Campbell of Williamsburgh in Virginia.” Joseph Reed sent one of the prints to Martha Washington. It amused the general, who wrote that the artist, whoever he was, had “made a very formidable figure of the Commander-in-Chief, giving him a sufficient portion of terror in his countenance.” Alas, Washington pointed out, he had never met Mr. Campbell of Williamsburg. No artist of that name is known to have worked in Virginia.

The portraits were mostly fraudulent, turned out quickly to meet public demand for images of the leaders of the American rebellion. All of the prints may, in fact, have been produced for the London market in Augsburg, a German city that was a center of commercial print production. Their style—the markedly heavy features, large eyes, dark shadows, and treatment of details of clothing and accoutrements—is characteristic of Augsburg engravings.

Even more curious, the names of Thomas Hart, C. Shepherd, and John Morris seem to be fictitious as well. With one exception, their names are not associated with any other prints. The only plausible explanation for the use of these fictitious names is that the true publishers wanted to profit by selling images of the American Revolutionaries but preferred not to be closely associated with these products, which were, after all, heroic images of traitors who had taken up arms against the king.

The Hero returned from Boston is the outlier among the odd prints published by the fictitious Thomas Hart. It is the only etching, with aquatint or otherwise, associated with Hart’s name. The Hero returned from Boston is also the only one of the Hart prints in which the subjects are not named. Who is the hero returned from Boston? And who is the woman clinging so provocatively to him?

Since Hart’s name was associated with prints of American rebels we might jump to the conclusion that the hero is George Washington and the scantily clad woman is Martha, welcoming the general home from his victory in the Siege of Boston, and that the print was intended to mock the American rebel chieftain. Entertaining as that solution might be, evidence suggests the leering hero and his bare-breasted companion are another couple.

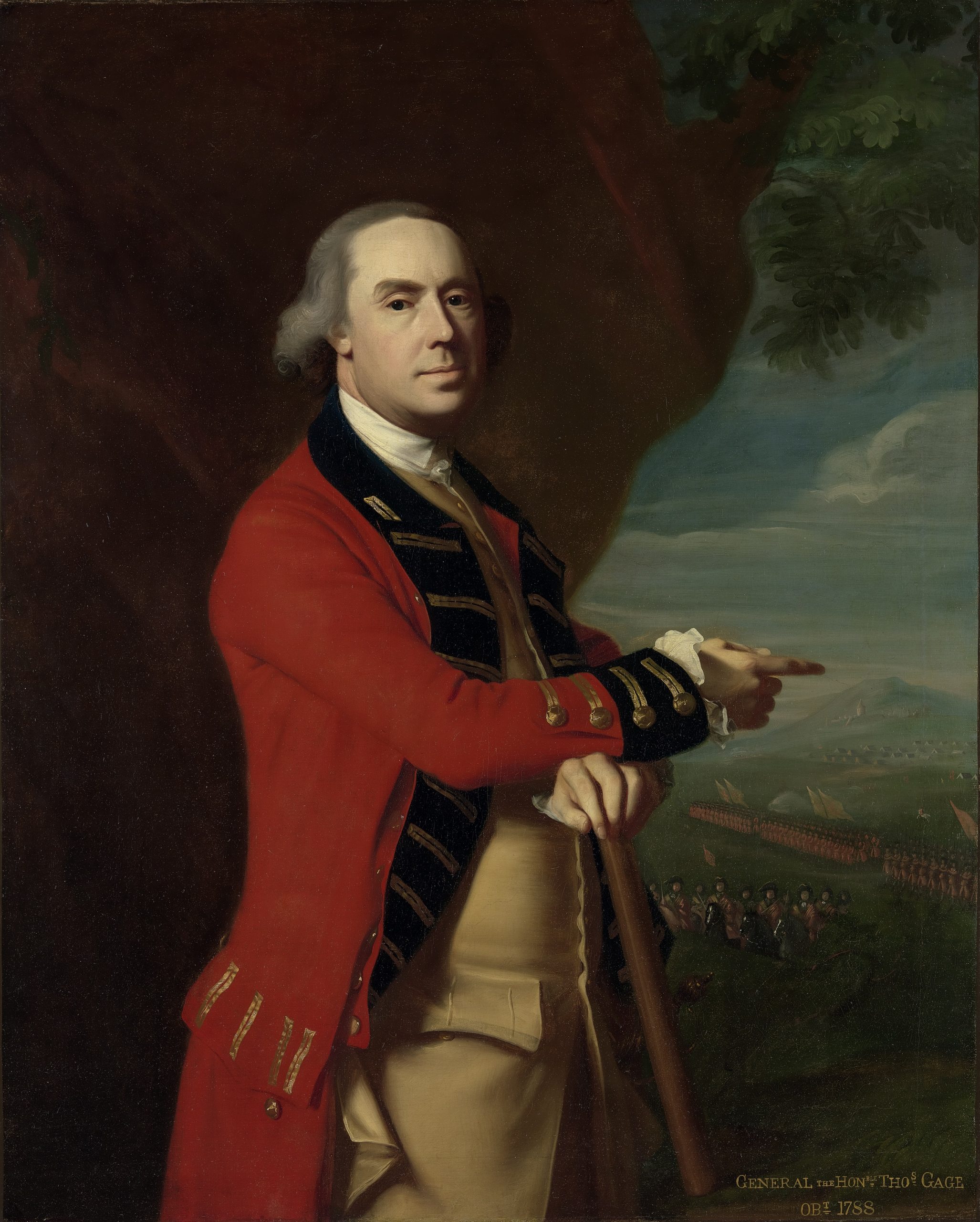

The man in the print bears a casual resemblance to General Thomas Gage as portrayed by John Singleton Copley in 1768. Gage had commissioned the portrait and when it was complete, sent it home to England. “The Generals Picture was received at home with universal applause,” one of Gage’s aides reported to Copley in 1770, “and Looked on by real good Judges as a Masterly performance. It is placed in one of the Capital Apartments of Lord Gage’s house in Arlington Street.”

John Singleton Copley began his portrait of Thomas Gage in the fall of 1768, when the general traveled to Boston to oversee the occupation of the city by British Regulars (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

We remember Gage as the first British general whose career was wrecked by the American Revolutionary War, which would ruin the careers of William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton, each in turn. Of the principle British commanders in America, only Charles, Lord Cornwallis—humiliated at Yorktown—salvaged his career. A successful governor-general of India, he lies in a monumental tomb overlooking the Ganges and is memorialized in Saint Paul’s Cathedral.

None of the four equaled the rise of Thomas Gage. He came to America as a lieutenant colonel under Gen. Edward Braddock. He distinguished himself in Braddock’s disastrous expedition against Fort Duquesne and thereafter rose through the senior ranks of the army. He was promoted to colonel in 1758. That same year he married Margaret Kemble, the beautiful daughter of a wealthy New Jersey merchant. Gage served in Jeffrey Amherst’s operations against Montreal and was then appointed governor of Montreal. A major general by 1761, Gage became acting commander in chief of British forces in North America in 1763 and officially succeeded Amherst in that role in 1764.

As His Majesty’s commander in chief Gage was responsible for disseminating information and instructions from London, enforcing acts of Parliament, settling disputes between the fractious colonial governments, policing the frontier, managing relations with the Indians, maintaining dozens of forts, defending imperial posts, and coordinating colonial defenses. Gage maintained communications with the governors of every colony in North America and several West Indian islands.

He handled his vast and varied administrative responsibilities with skill, even as relations between Britain and the colonies deteriorated. In 1770 he was promoted to lieutenant general. He was widely admired—a hero, even—on both sides of the Atlantic. Many Americans regarded him as one of their own. He purchased thousands of acres in upstate New York and in what became New Brunswick to leave to his growing family. When Gage went to England on a leave of absence in the spring of 1773, dozens of American leaders, including George Washington, gathered at a party in New York to see him off.

During the year that Gage was in England, American affairs reached a crisis. The Crown sent him back to America not only as commander in chief but also as royal governor of Massachusetts charged with implementing Parliament’s punitive measures against that colony.

Within a year his career unraveled. The military occupation of Boston infuriated the colonists and fueled resistance. Gage’s military force was wholly inadequate to suppress the insurrection. It never controlled more than the ground on which it stood and often not even that much. A force he sent to Concord in April to seize weapons stockpiled by the resistance was mauled by militia. Nine weeks later he lost hundreds more soldiers in an assault on rebel militia on the Charlestown Neck in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Gage received orders recalling him to London on September 26, turned his command over to General Sir William Howe on October 10, and arrived in London on November 14. The next day he met privately with the king, who showed no inclination to blame Gage for what had happened in America. It was hardly a hero’s return.

The resemblance of the man in The Hero returned from Boston to Copley’s portrait of Thomas Gage is superficial at best, but the resemblance of the woman to Copley’s portrait of Gage’s wife, Margaret Kemble Gage, is striking. The Hero returned from Boston is a commentary about husband and wife.

Copley painted Mrs. Gage in 1771 in a languid pose wear wearing an iridescent Turkish style caftan over a lace trimmed chemise with an embroidered belt at her waist. Pearls and a turban-like swath of drapery adorn her hair. This style, known as turquerie, was the height of fashion for masquerade balls in Europe, but was largely unknown in British America, where women had no opportunity to wear such attire, which was intended to suggest the costumes worn by Turkish women in the Ottoman court. It was a style western Europeans imagined was fashionable in the sultan’s harem, a symbol of Oriental luxury and vice. Most western European turquerie bore only a slight resemblance to Ottoman costume, but it symbolized what western Europeans imagined the Turkish court was like—a mysterious place where powerful men kept women for pleasure and where exceptional women used their physical charms to dominate and control men.

John Singleton Copley portrayed Margaret Kemble Gage in exotic attire inspired by the Turkish court (Timken Museum of Art).

Part of the attraction of turquerie was that it was sexually suggestive without being lewd. In Copley’s portrait Mrs. Gage is not wearing a corset and reclines in her loose fitting clothes. Copley called it “beyond Compare the best Lady’s portrait I ever Drew.” Proud of the portrait, the Gages packed it off to London, where it created a mild sensation when it was displayed.

Copley played on the fact that Margaret was known as a touch exotic. She was one quarter English, one quarter Greek, one quarter Dutch, and one quarter French. Her father, Peter Kemble, was the son of an English merchant who traded with Ottoman Empire. Peter was born in Smyrna, a Greek enclave on the Turkish coast. His mother—Margaret’s grandmother—was a Greek woman from the nearby island of Chios. Peter arrived in New York around 1730 and settled in New Jersey, where he quickly established himself as a merchant and became the largest landowner in Morris County. His first wife, Getrude Bayard—Margaret’s mother—made Margaret a cousin to the de Lanceys, van Courtlands and other prominent New York families.

Peter Kemble was proud of his Greek background. So was his daughter, who was recognized in New York society for her unusual beauty and self-assurance. Through most of Gage’s service as commander in chief he made his headquarters in New York City, where Margaret—attractive, vivacious, outgoing, and well connected—was the perfect wife for an ambitious, rising general. Her husband’s military subordinates referred to her as “the dutchess.” She was a talented hostess and bright conversationalist. The general and his wife were rarely apart.

Margaret returned to America with her husband in 1774, but circumstances had changed. The general made his headquarters in Massachusetts, where she had few acquaintances. As relations between the colonists and the army degenerated some of her husband’s British subordinates found her American birth, self-confident manner, and intimate relationship with their commander had become reasons to distrust her. So did many Massachusetts loyalists, to whom she was an exotic stranger. She was connected to all the best families in New York and navigated among them with skill and grace, but this meant little to the clannish loyalists of eastern Massachusetts. She was not one of them.

Rumors went around that Margaret Gage was sympathetic to the rebellion, despite the fact that her father was a loyalist, her brother was a major in the British army and deputy adjutant general, and her husband was commander in chief of the king’s forces in North America. The displaced governor, Thomas Hutchinson, noted that she had once said to him that “she hoped her husband would never be the instrument of sacrificing the lives of her countrymen,” but her husband probably shared that sentiment. The war was a tragedy for their family as it was for the empire.

The rumors had no foundation, but the idea that the army’s secrets were being betrayed by someone close to the general offered an explanation for what seemed so inexplicable: British soldiers cut down by colonial militia, trapped in Boston by provincials, impotent to suppress a colonial rebellion led by farmers.

With Boston under siege, beset by food shortages and disease and filled with hundreds of wounded soldiers mangled in battle, Gage put Margaret on a ship bound for England in August 1775. The vessel was filled with women, children, and scores of wounded British soldiers. The voyage was miserable. When the ship reached Plymouth, a witness recorded that “a few of the men came on shore, when never hardly were seen such objects! Some without legs, and others without arms; and their cloaths hanging on them like a loose morning gown, so much were they fallen away by sickness and want of proper nourishment … the vessel itself, though very large, was almost intolerable, from the stench arising from the sick and wounded.”

Rumors of veiled disloyalty preceded Margaret Gage to London and were current when she and her husband were reunited in November. The general, his critics implied, was uxorious, a word not much used today, but which Dr. Johnson’s eighteenth-century dictionary defines as “submissively fond of a wife; infected with connubial dotage.” The rumors served to explain how the American rabble had repulsed the flower of the king’s army and trapped it in Boston.

The Hero returned from Boston plays on the theme of Oriental seduction. The woman, who is clearly Margaret Gage, stands up from the upholstered couch on which Copley had placed her. Her belt is discarded and the Turkish caftan has slipped from her shoulder as she wraps herself around the general, taking control, the embodiment of vice and corruption. The reunion of husband and wife reveals Gage’s weakness and explains his failure and the army’s humiliation. “Gage poor wretch is scarcely thought of,” an artillery officer wrote, “he is below contempt.”