Emily Northcutt, Classical Center at Brandenburg Middle School, Garland, Texas

DESIGN LEVEL: Middle School

Overview

This lesson will explore the era of the Early Republic and reinforce understanding of how the Revolutionary War directly influenced the creation of the United States Constitution. The Revolution’s highest ideals heavily influenced political leaders, artists, and common people. Students will examine the ideals of liberty, equality, civic responsibility, and natural and civil rights, and connect them to the formation of the American Republic following the Revolutionary War, then complete an independent project connecting republican ideals to physical artifacts.

Objectives

Students will . . .

- Identify the highest ideals of the United States following the Revolutionary War.

- Connect physical artifacts to political and social ideals by considering the following questions:

- What is a republic? Why did America chose this model of government?

- What does it mean to be a republic? Has America upheld that ambition?

- Does our governmental system reflect the high ideals expressed during the American Revolution? What have been our shortcomings? Do we still hold these high ideals?

- How were the objects created during America’s Early Republic significant at the time? Why do they matter now? Are there examples of twenty-fist century objects that convey those early republican ideals?

Materials

- “He Comes the Hero Comes,” David and Ginger Hildebrand, Colonial Music Institute, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, The Music of Washington’s World, December 17, 2015

- The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati, Discover the Collections

Recommended Time

One 50-minute class, with a homework assignment.

Activity

Bell Ringer: Play the video excerpt of “He Comes the Hero Comes,” prompting students to listen closely and construct a word cloud with significant words or phrases they hear as well as significant ideas that come to mind. Discuss what this song reflects about George Washington’s reputation and the feeling of Americans following the Revolutionary War.

Introduction: The United States has won the Revolutionary War and is a free and independent country. Ask students to discuss the following questions:

- As a new republic, what does our nation represent?

- Who or what do we look to for inspiration?

- What do the republic’s ideals of liberty, equality, civic responsibility and natural and civil rights mean to you?

- Did these ideals mean different things to different people in the eighteenth century?

Exploration: Physical objects provide clues about the past. By examining items that reside in museum collections and elsewhere, we can learn about people’s lives and how they viewed the world in which they lived. These objects reflect the values held by the people who possessed them, from a society’s leaders to its common people as well. The song “He Comes the Hero Comes” demonstrates how music reflects the thoughts of those who created, listened to, and passed on lyrics and melodies of the past. Direct students explore the online collections of the American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati at https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/discover-the-collections/ and to think about what these objects reflect about the ideals of the Early Republic. Remind students that these collections contain examples from all walks of life, representing evidence about how different groups felt at the time.

Assignment: Have students select an item from the gallery below and conduct a See, Think, Wonder object analysis to infer more about the item’s history and purpose, then ask students explain what the object suggests about how its creator and owner thought or felt about the highest ideals of the Early Republic.

Evidence of Learning: On-level students will create a one-page Google Slide, and honors students will complete a Google Doc quick-write answering the following questions:

- What do you see? Are there any symbols or metaphors? Does the object relate to any other periods of history?

- What is the artifact, and how was it used?

- Do we have similar objects today? How are twenty-first century objects different?

- How can I connect the significance of this artifact to the present? For example: Broadsides could be used as propaganda: what kind of propaganda exists today? Maps and weapons have always been important for military strategy: what do military maps look like now? how have weapons changed over the centuries?

- What do these artifacts suggest about the political or social ideals of the time? Do they continue to suggest these ideals today? In your opinion, did these objects influence the building of the American Republic—explain how they reflect the republic ideals of liberty, equality, civic responsibility and natural and civil rights we discussed as a class.

Extension Activity: Ask students to find items created in the twentieth or twenty-first century that reflect the American Revolution’s highest ideals.

Standards Addressed

19 TEXAS ADMINISTRATIVE CODE CHAPTER 113. TEXAS ESSENTIAL KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS FOR SOCIAL STUDIES

Subchapter B. Middle School, 113.20. Social Studies, Grade 8, Adopted 2018

1.A-B, History. The student understands traditional historical points of reference in U.S. history through 1877.

4.A-D, History. The student understands significant political and economic issues of the revolutionary and Constitutional eras.

5.A, 5.C, 5. E, History. The student understands the challenges confronted by the government and its leaders in the early years of the republic and the Age of Jackson.

15.C, Government. The student understands the American beliefs and principles reflected in the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and other important historic documents.

19.A, 19.C, Citizenship. The student understands the rights and responsibilities of citizens of the United States.

20.A, Citizenship. The student understands the importance of voluntary individual participation in the democratic process.

22.A, Citizenship. The student understands the importance of effective leadership in a constitutional republic.

23.C-D, Culture. The student understands the relationships between and among people from various groups, including racial, ethnic, and religious groups, during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

26.A-B, Culture. The student understands the relationship between the arts and the times during which they were created.

29.A-E, Social studies skills. The student applies critical-thinking skills to organize and use information acquired through established research methodologies from a variety of valid sources, including technology.

30.B-C, Social studies skills. The student communicates in written, oral, and visual forms.

Jug

Probably Herculaneum Pottery, Liverpool, England

ca. 1800The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

One side of the jug shows an oval map of the United States of America surrounded by figures drawn from the cartouche of the same map published in London in 1783 by John Wallis. At the left of the map, George Washington is depicted in military uniform walking alongside the female allegorical figure of Liberty, who holds a liberty pole and cap. The winged figure of Fame flies overhead, blowing a trumpet and holding a crown of laurel leaves and a ribbon bearing the name "Washington." To the right of Fame is a variation of the American flag that includes the Great Seal in the center. At the right of the map, Benjamin Franklin is seated with the goddess Athena looking over his shoulder and the figure of Justice to the side, with two pine trees behind them.

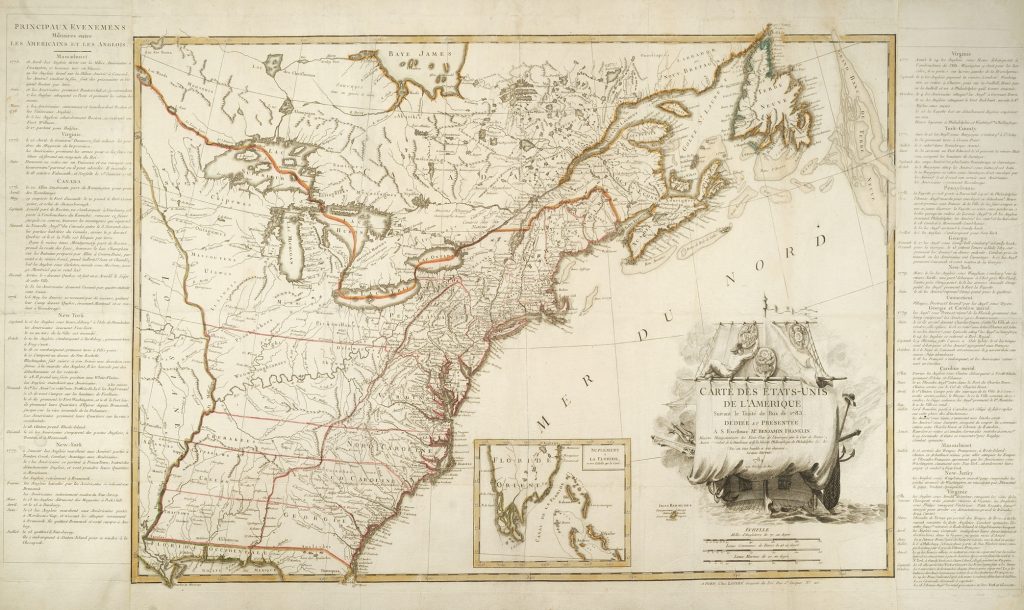

Carte des Etas-Unis de l'Amerique suivant le Traite de Paix de 1783

Paris: Chez Lattre, Graveur du Roi, 1784The Society of the Cincinnati, Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Dedicated to Benjamin Franklin, this is the first map to delineate the full extent of the United States of America after the ratification of the Treaty of Paris. The cartouche features symbols of the new American nation, including the Great Seal of the United States and the Eagle of the Society of the Cincinnati. This rare first state of the first edition of Lattre's map includes a detailed chronology of the war affixed to the left and right margins. [2012]

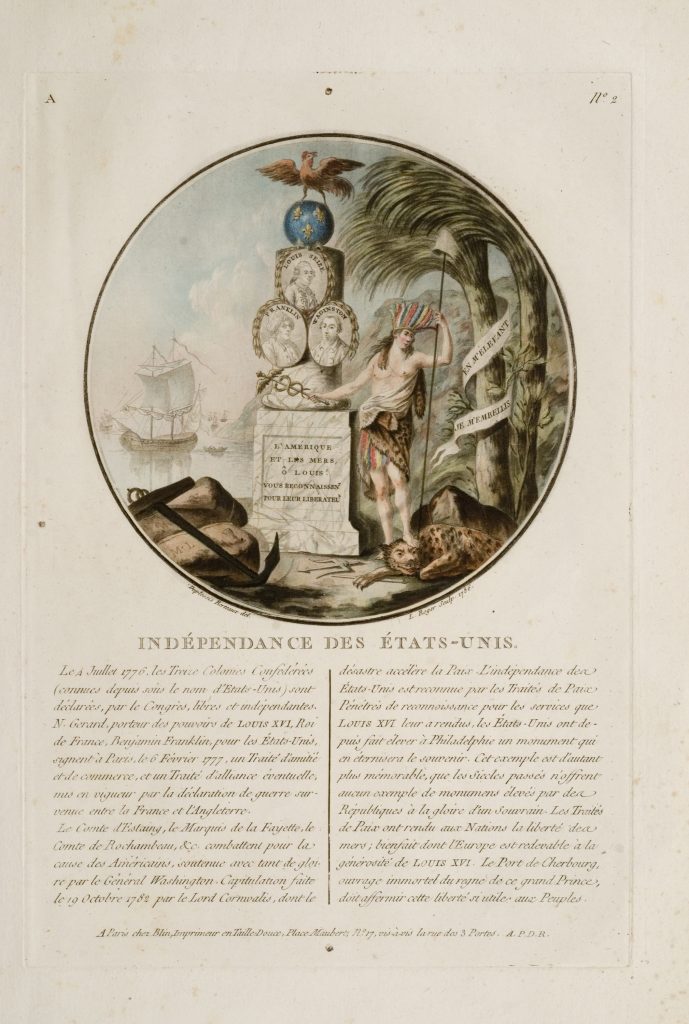

Indépendance des États-Unis

L. Roger, engraver; after Jean Duplessis-Bertaux, artist

Paris: Chez Blin, 1786The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This allegorical image celebrates the alliance of France and the United States and their victory over Great Britain. America is represented by a Native American woman resting her foot on the defeated British lion. She stands beside a monument bearing portraits of Louis XVI, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington.

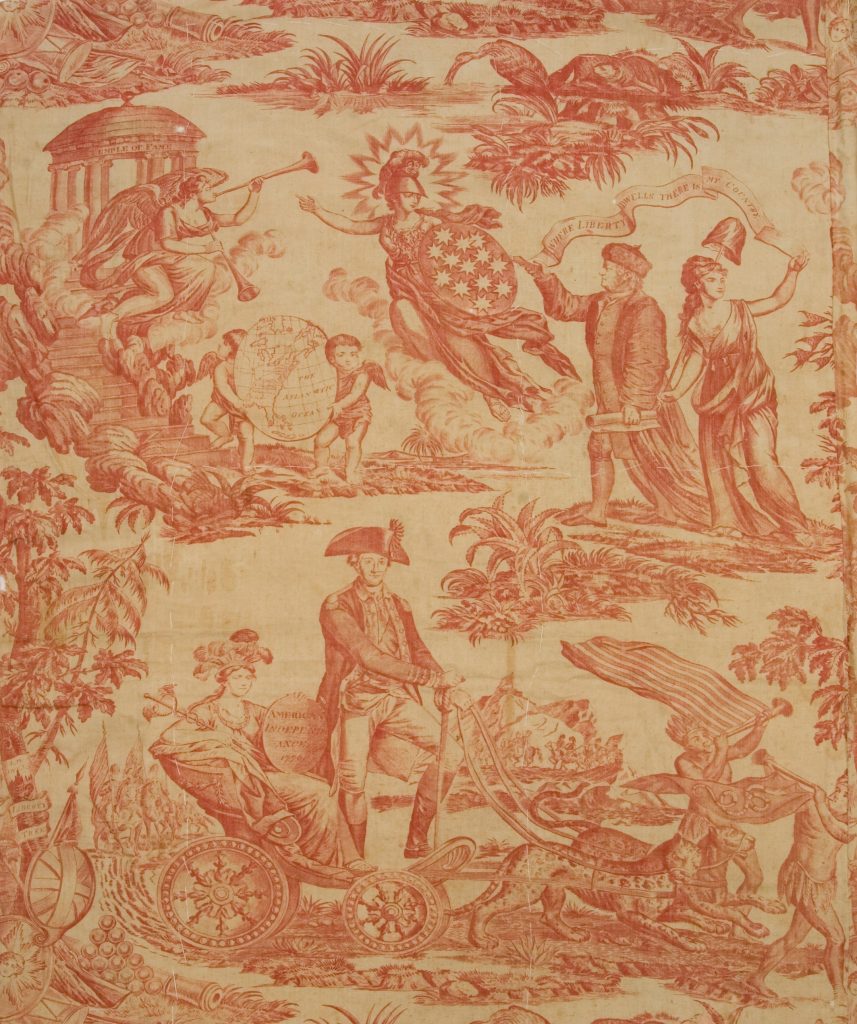

"Washington and American Independance, The Apotheosis of Franklin"

English

ca. 1785Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Paul William Cook, Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation, 1959

"Washington and American Independance (sic), The Apotheosis of Franklin" (alternately known as "The Apotheosis of Franklin and Washington") copperplate-printed bed furnishing in red on white cotton or cotton-linen blend, made in England, ca. 1785. Pattern depicts George Washington in military uniform standing in a chariot alongside a seated female figure of America, who holds a caduceus in one hand and an oval plaque inscribed "AMERICAN / INDEPEND/ ANCE [sic] / 1776" in the other hand. The chariot is pulled by two leopards, which are flanked by two American Indians, one holding a thirteen-striped flag and the other a flag bearing a rattlesnake inscribed "Unite or Die" and cut into thirteen parts. Soldiers carrying striped flags descend from a mountain and follow the chariot. Behind the chariot is the (labeled) Liberty Tree, bearing an upside-down placard reading "Stamp Act." Above Washington, the pattern depicts Benjamin Franklin next to the personification of Liberty, and the two hold a banner inscribed "WHERE LIBERTY DWELLS THERE IS MY COUNTRY." On the other side of Franklin is the goddess Athena, carrying a shield with thirteen stars and pointing to the Temple of Fame, and two putti holding a globe showing America divided into Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and New England. The winged figure Fame holds two trumpets and flies in front of the temple. Above Franklin are a beaver and a heron with a fish in its mouth shown in a marsh. The textile may have originally been a bed curtain or bedspread, and may have been converted into a drape or hanging at a later date.

Badge of Military Merit

ca. 1782-1783Collection of the American Independence Museum, Exeter, NH and the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Hampshire. Gift of William L. Willey.

George Washington created the Badge of Military Merit—the first military decoration for enlisted men—on August 7, 1782. The award recognized distinguished conduct and was intended to encourage “virtuous ambition” and “every species of Military merit.” Soldiers honored with the award “shall be permitted to wear on his facings over the left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth, or silk, edged with narrow lace or binding.” Only two reputed examples are known, of which this is one. The decoration fell out of use after the Revolutionary War but was revived in 1932 as the modern Purple Heart.

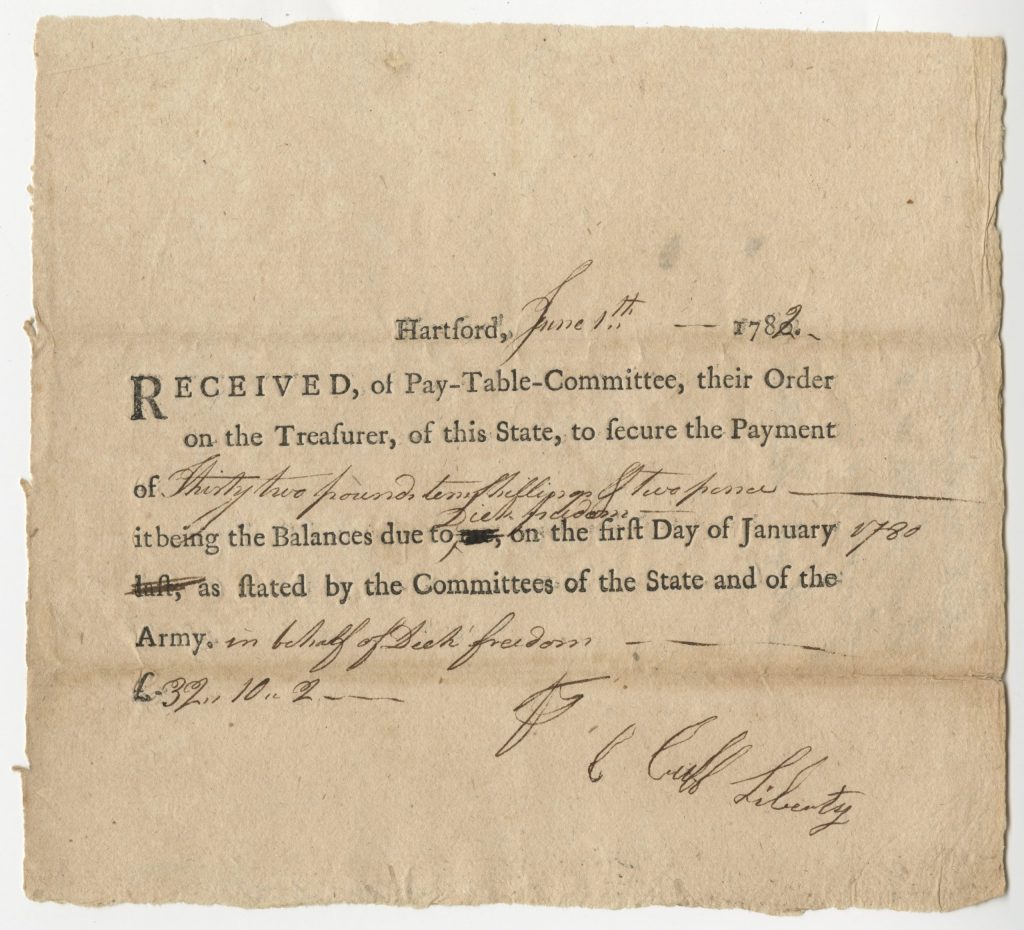

Partially printed D.S., Hartford, June 7th 1782: receipt of Pay-Table-Committee

Cuff Liberty, Dick Freedom, Committee of the Pay Table; Connecticut. Treasury Dept.

1782The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Payment receipt signed for Dick Freedom by Cuff Liberty. Dick Freedom and Cuff Liberty were African American participants in the Revolutionary War who adopted aspirational names during their service. They served in the all-African American Second Company of the Fourth Connecticut Regiment.

Voltaire medal

François-Marie Arouet, artist; Struck in Paris

1778The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Benjamin Franklin and the French philosopher Voltaire collaborated to produce this bronze medal in honor of George Washington. The obverse depicts a generalized portrait of the general—as no true likeness of Washington existed in France at the time. The reverse displays military symbols and a Latin inscription meaning, “Washington combines in a single union the talents of a warrior and the virtues of a philosopher.”

Anti-Slavery Medallion, Am I Not A Man and A Brother

Henry Webber, artist; Struck in Great Britain

1787The Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State

This anti-slavery medallion was produced as part of the late 18th century abolitionist movement in Western Europe and America. Many abolitionists wore these medallions to clearly state their position and start conversations about slavery. These small porcelain and ceramic medallions were designed and produced by a team of craftsmen led by British potter Josiah Wedgwood. Over time, the medallions’ popularity grew, and the image appeared on a variety of objects, including chinaware, cufflinks, and pamphlets distributed by and among the activists.