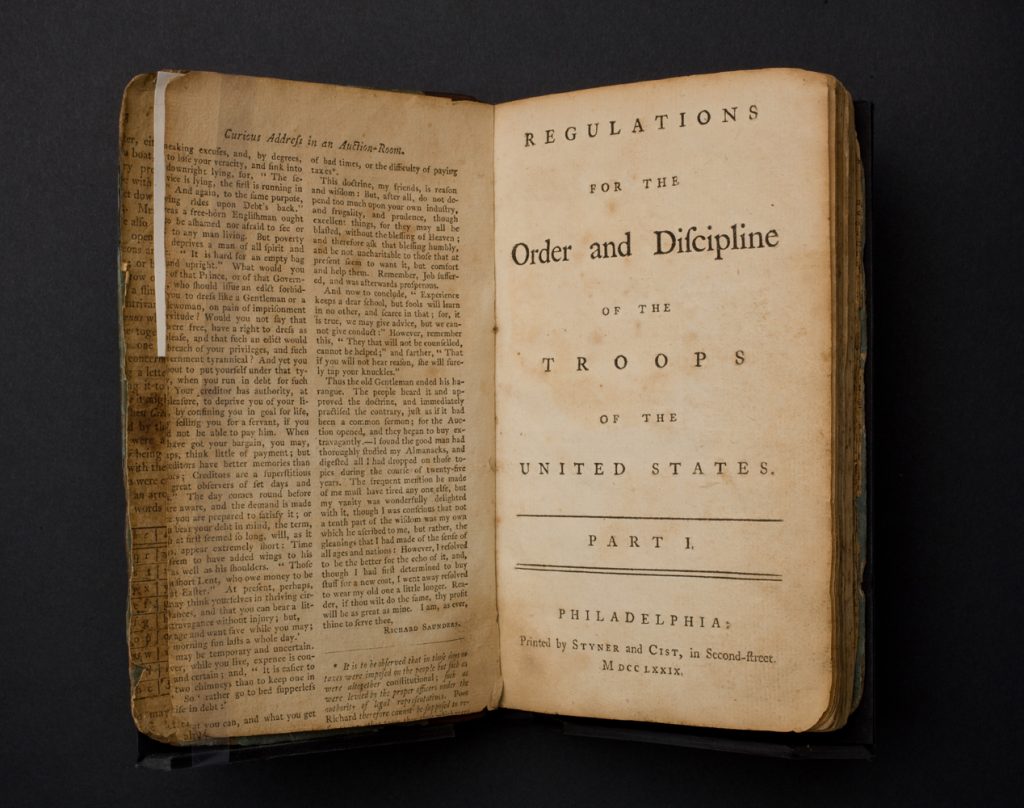

No book shaped the Continental Army more than Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States written by Prussian-born general Friedrich Wilhelm Steuben. Published mid-war by an act of Congress in 1779, it codified for the first time the governance of the army, from the basic drill to the specific duties of each officer rank. The Regulations’ wide distribution to the troops, who called it the “Blue Book” after its blue paper-covered covers, was a crucial step in building the fighting force that would win American Independence. The American Revolution Institute holds five copies of the first edition of the Regulations, all but one bearing evidence of the original officer who owned them.

Soon after he took command of the American forces in 1775, George Washington recognized the need for a standardized drill manual that would bring unity and consistency to the training of the Continental troops. Through the early years of the war, Washington promoted the use of several published works, including Timothy Pickering’s An Easy Plan of Discipline for a Militia and Thomas Hanson’s The Prussian Evolutions, but it was not until 1779 that circumstances brought the right individuals together to produce the first official manual of the Continental Army. The key was the arrival of Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Steuben of Prussia, a former aide to Frederick the Great, who came to America in late 1777 to volunteer his services to the cause for independence. He joined General Washington at Valley Forge in February 1778 and quickly made himself indispensable in bringing new order and discipline to the troops suffering under wretched winter conditions. Recognizing his genius as a military instructor, Washington petitioned Congress to commission Steuben to the post of inspector general with the rank of major general.

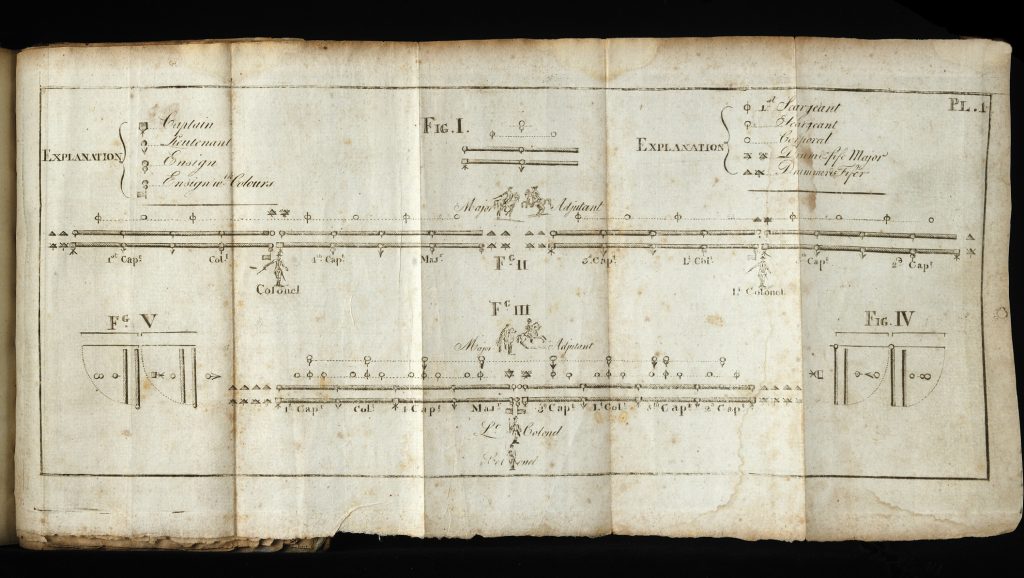

At the close of the campaign of 1778, Washington assigned Steuben and his staff to Philadelphia to begin work on his long-desired manual of regulations for the army. The writing and editing of the work involved a laborious series of steps. Steuben, who spoke little English, wrote each passage in practical, simplified French. His staff, which included François-Louis Teisseydre de Fleury, Pierre Etienne Duponceau and Benjamin Walker, edited it into literary French and then translated it into English. To further clarify the instructions, drawings for eight folding plates to accompany the text were prepared by another member of Steuben’s staff, Pierre-Charles L’Enfant (who would later design the Society of the Cincinnati’s insignia).

As Steuben and his staff worked, drafts of their manuscript of the Regulations were sent to General Washington, who added his own corrections and additions. Returning a portion of the manuscript on February 26, 1779, Washington wrote:

I very much approve of the conciseness of the work, founded on your general principle of rejecting everything superfluous; though perhaps it would not be amiss in a work of instruction, to be more minute and particular in some parts. One precaution is rendered necessary by your writing in a foreign tongue, which is to have the whole revised and prepared for the press by some person who will give it perspicuity and correctness of diction, without deviating from the appropriated [sic] terms and language of the Military Science. These points cannot be too closely attended to, in Regulations which are to receive the sanction of Congress and are designed for the general Government of the Army.

Washington returned the final portion of the manuscript, marked with his corrections and additions, on March 11. Meanwhile, Steuben and his staff were busy incorporating Washington’s changes, converting the text to simple, correct English suitable to its purpose, and overseeing the engraving of L’Enfant’s drawings onto copperplates.

The final draft of the Regulations was examined and approved by the Board of War and forwarded on to Congress, with a recommendation for official adoption: “It has been examined with attention by the Board and is highly approved, as being calculated to produce important advantages to the States. We believe to join the Baron in praying it may as soon as possible, have the sanction of Congress, that it may be committed to the press with the expedition which the advanced season of the year requires.” On March 29, 1779, Congress passed a resolution ordering that the Regulations “be observed by all the troops of the United States, and that all general and other officers cause the same to be executed with all possible exactness.” The Board of War was given the authority to “cause as many copies thereof to be printed as they shall deem requisite for the use of the troops.”

The Philadelphia firm of Styner and Cist was selected as the government’s official printer for the Regulations. An exacting taskmaster, Steuben planned to stay in Philadelphia to oversee every aspect of the publication process. He was greatly frustrated by delays caused by shortages of supplies and workers, and he was forced to turn over the final proofing and inspection of the binding to his aides, while he went on to join Washington’s camp at Middlebrook, New Jersey, at the end of April.

The contract for binding the work went to Robert Aitken, the foremost binder in the city. Aitken was also hampered by an extreme shortage of supplies and a work force diverted to the war effort, leaving him to work virtually alone on the Regulations assignment. The initial engravings for the copperplates done by John Norman had proved to be unsatisfactory, and a second engraver was called in to create new plates. As months passed, Steuben grew angry and frustrated, complaining bitterly of the delays in letters to the Board of War and Congress. It was not until November 1779 that Aitken finally completed binding the first edition of the Regulations, a total of nearly three thousand copies.

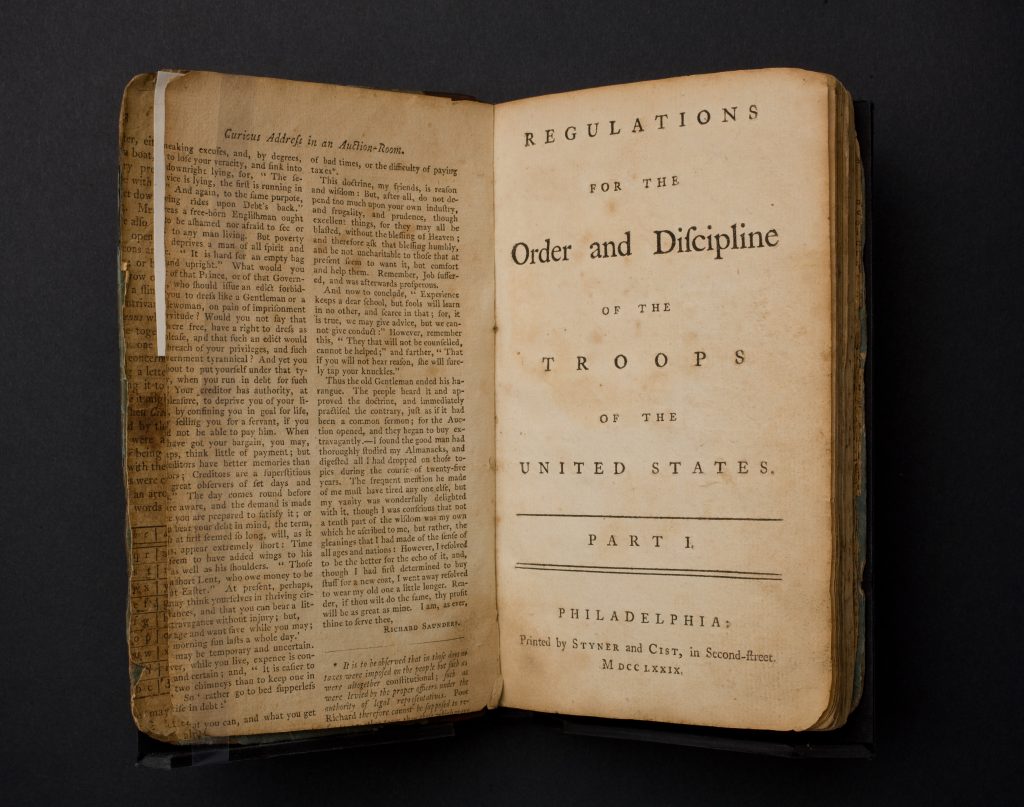

The majority of the copies were half-bound in blue paper-covered boards, with simple leather spines. Facing paper shortages, Aitken used overruns from his printing of The Pennsylvania Magazine for the front and back endpapers and flyleaves. At Steuben’s request, Washington’s personal copy, which includes L’Enfant’s original drawings, was elegantly bound in leather and tooled in gold leaf—the latter a truly scarce commodity in wartime Philadelphia. For his “indefatigable” work on the Regulations over a period of six months, the Board of Treasury issued a warrant to pay Steuben four thousand dollars, and another twenty-five hundred dollars to be divided among his aides.

In the 164-page Regulations, Steuben presents a standardized drill for the infantry, laid out command by command. The book also includes the official regulations for military conduct, from administration and courts-martial to sanitation and hygiene, and a guide to the duties and responsibilities of each officer rank in the army. From the time it appeared in print, General Washington emphasized the use of the Regulations in his general orders and letters to his officers. The orderly books in the Institute’s collections contain at least a dozen direct references to the new manual and its rules. In one, kept for the Ninth Pennsylvania Regiment at Morristown during the harsh winter of 1780, Capt. Jacob Bower recorded Washington’s order that “the officers commanding Division & Brigades, by the closest personal attention to the Police of their Respective Corps to correct those disorders & introduce an exact conformity of the Regulations for the order and discipline of the troops of the United States Established by Congress.”

Three years later, the Regulations remained at the center of Washington’s system of discipline. In a letter written at Newburgh on January 25, 1783, Washington severely reprimanded Maj. Thomas Lansdale, commander of the Maryland Detachment, for the disorderly appearance of his men and the filthy conditions of his camp, and recommended “in pointed terms to your officers the necessity, and advantage of making themselves perfectly masters of the Printed ‘Regulations for the Order & Discipline of the Troops of the United States.’ Ignorance of them cannot, nor will it be any excuse.”

Four of the first-edition copies of the Regulations in the Institute’s collections bear ownership inscriptions of Continental officers who became original members of the Society of the Cincinnati, including Capt. James Beebe (Continental Sappers and Miners), Surgeon John R. Watrous (First Connecticut Regiment), Maj. Nicholas Fish (Second New York Regiment and a division inspector under General Steuben), and Capt. William Helms and Lt. Samuel Moore Shute (Second New Jersey Regiment), whose signatures appear within the same volume.

The title page of the first edition of the Regulations—which does not bear the name of its author—states that it is “Part I.” If General Steuben or Congress had further plans for a companion volume, none was published. Five additional editions of the Regulations were published during the war: in Boston in 1781; in Boston, Hartford and Philadelphia in 1782; and in Hartford in 1783. Recognized as a landmark publication of the Revolution, Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States by Friedrich Wilhelm Steuben remained the official manual of the United States Army as well as state militias until the beginning of the War of 1812.

View More Rare Books

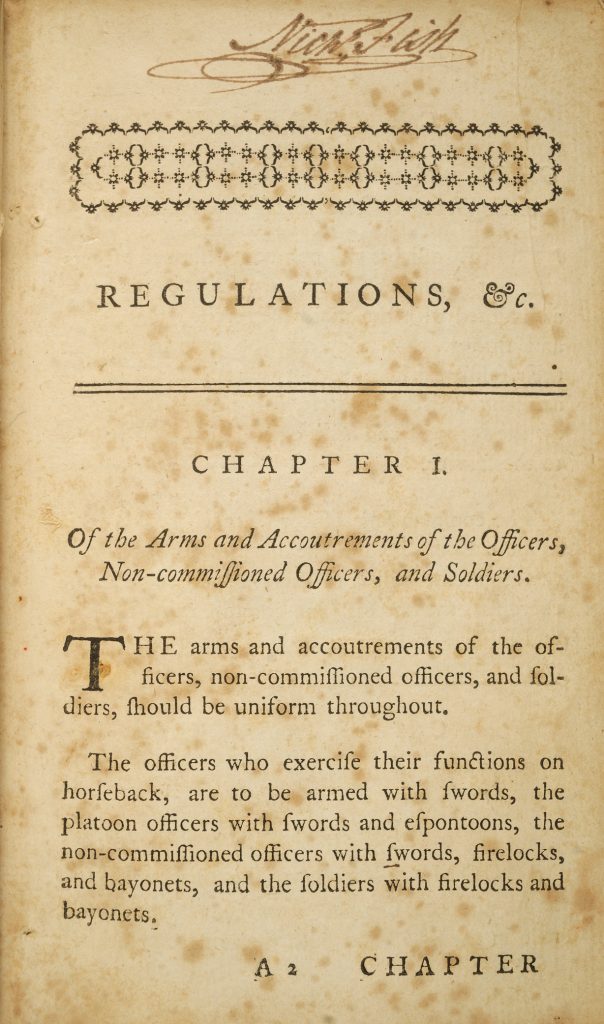

Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron von Steuben

Philadelphia: Printed by Styner and Cist, 1779The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Only a small proportion of the three thousand copies of the original edition of the Regulations survive. This example from the Institute’s collections originally belonged to Capt. James Beebe of Connecticut.

Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron von Steuben

Philadelphia: Printed by Styner and Cist, 1779The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The original blue paper-covered board binding on Capt. James Beebe’s copy of the Regulations is remarkably well preserved.

General Steuben from Portraits des Géneraux, Ministres et Magistrats qui se Sont Rendu Célèbres dans la Révolution des Treize États-Unis de l'Amérique Septentrionale

Benôit Louis Prevost, engraver; after Pierre Eugene Du Simitière, artist

Paris: Avec Privilège du Roi, 1781The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The original portrait of General Steuben upon which this engraving is based was drawn from life by the French artist Pierre Eugene Du Simitière in 1779, the year the Regulations was first published.

Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron von Steuben

Philadelphia: Printed by Styner and Cist, 1779The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The signature of Maj. Nicholas Fish of the Second New York Regiment appears on the first page of text of his copy of the Regulations.

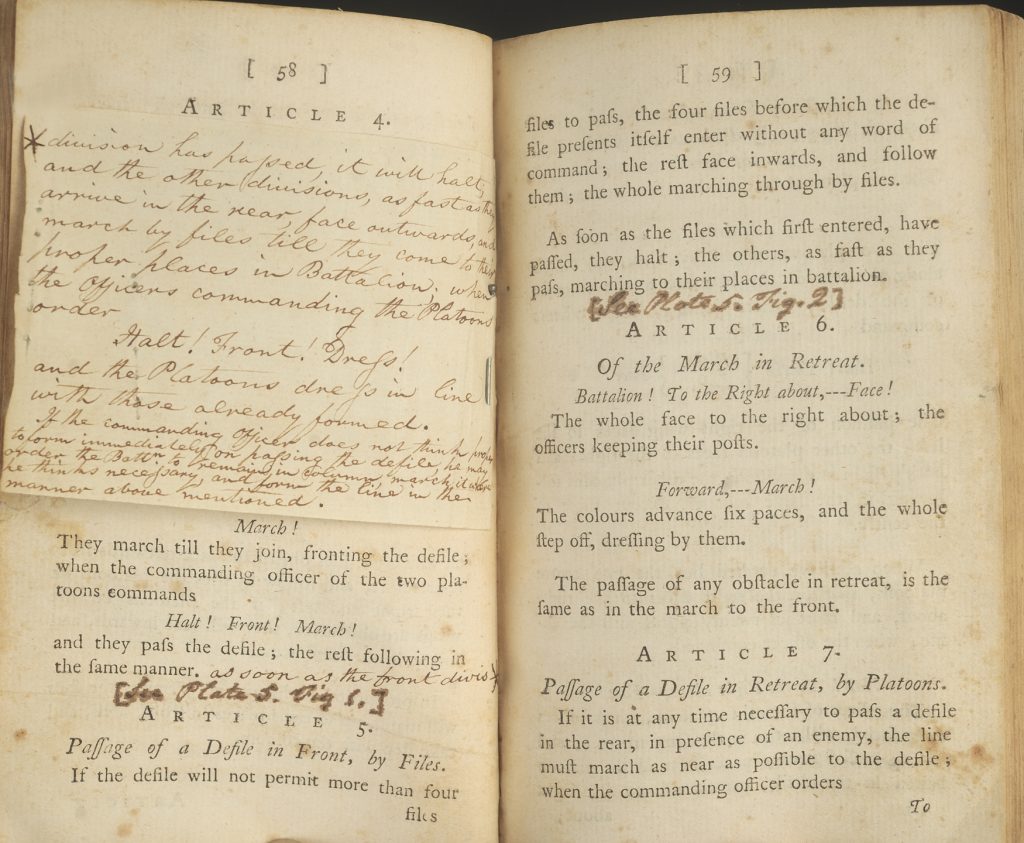

Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron von Steuben

Philadelphia: Printed by Styner and Cist, 1779The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Maj. Nicholas Fish annotated the instructions for marching in line in his copy of the Regulations.

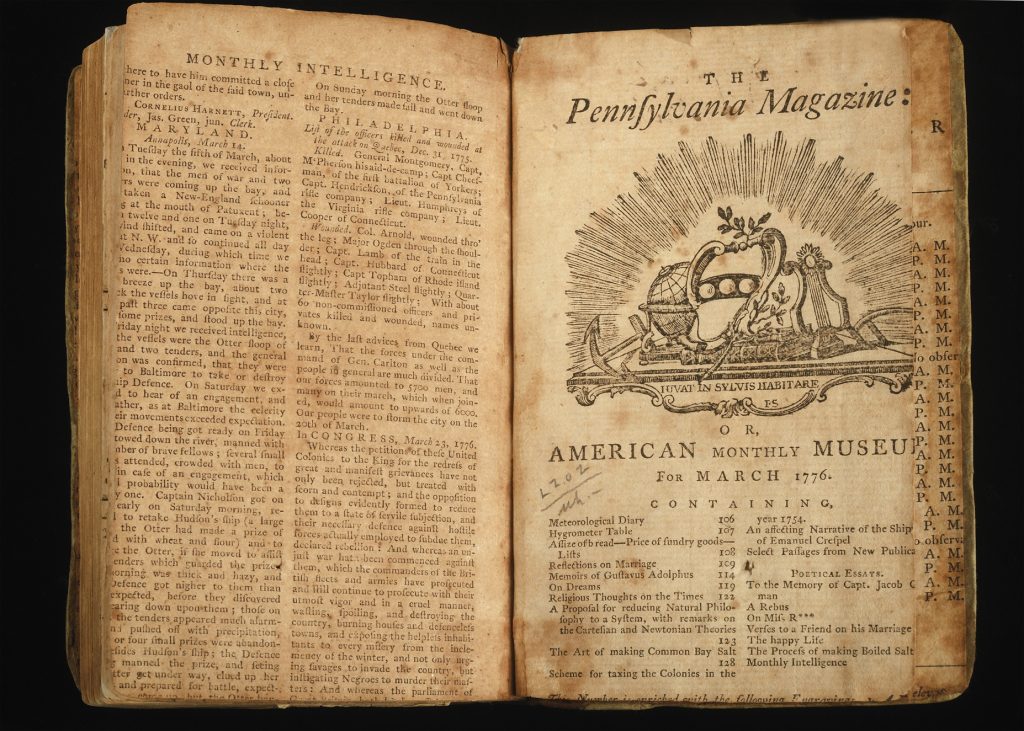

Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron von Steuben

Philadelphia: Printed by Styner and Cist, 1779The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Due to the shortage of paper, the binder Robert Aitken used scrap from overruns of The Pennsylvania Magazine for the flyleaves and endpapers of the printed Regulations.

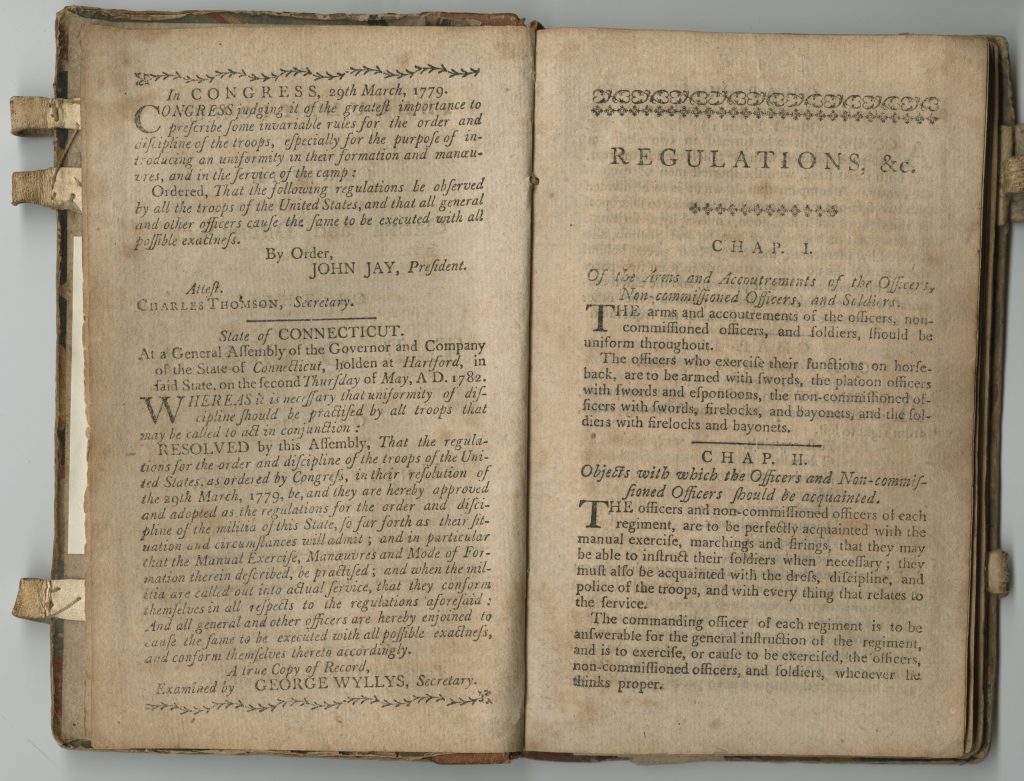

Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron von Steuben

Hartford, Conn.: Printed by Hudson and Goodwin, [1782]The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The 1782 edition of Steuben’s Regulations was published by the General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, which resolved that “the Manual Exercise, Manoeuvres and Mode of Formation therein described, be practiced; and when the militia is called out into actual service, that they conform themselves in all respects to the regulations aforesaid.”

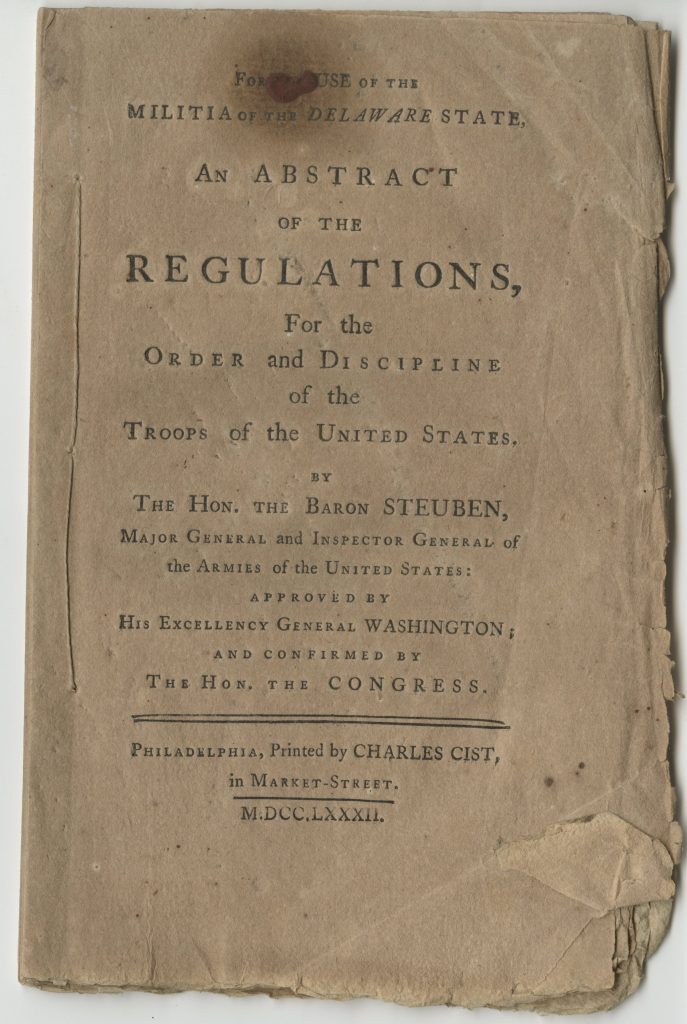

For the Use of the Militia of the Delaware State: An Abstract of the Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin, Baron von Steuben

Philadelphia: Printed by Charles Cist, 1782The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This volume opens with an address from John Dickinson, the president of Delaware, stating that he had arranged to have five hundred copies of this extract from Steuben’s manual printed for the use of the Delaware militia: “A trouble and expence I should have not incurred, if I had not been fully convinced that the work might be exceedingly useful. To render it so, is your part.”

Laws and Regulations for the Militia of the State of South Carolina

Charleston: From the Press of Timothy and Mason, 1794The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

In 1794, the South Carolina legislature resolved that “every commissioned officer…shall be furnished, at the expense of the state, with a copy of this law, the act of Congress to provide for national defense, Baron Steuben’s military discipline, and the articles of war, all bound together in a small convenient pocket volume.” The edition included this elaborate frontispiece that combines symbols of the United States, South Carolina and the military.