Revolutionary Beginnings: War and Remembrance in the First Year of America’s Fight for Independence

The War for American Independence began 250 years ago on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. From April 1775 to June 1776, Patriot, Loyalist, and British forces clashed in most of the thirteen American colonies, as well as Canada and the Caribbean. To commemorate the semiquincentennial anniversaries of these Revolutionary Beginnings, we are pleased to share a suite of classroom resources featuring the debut of our Year in Revolution video series spotlighting 1775 and 1776.

Learn more about our exhibition Revolutionary Beginnings: War and Remembrance in the First Year of America’s Fight for Independence.

from our IMAGINING THE REVOLUTION lesson series:

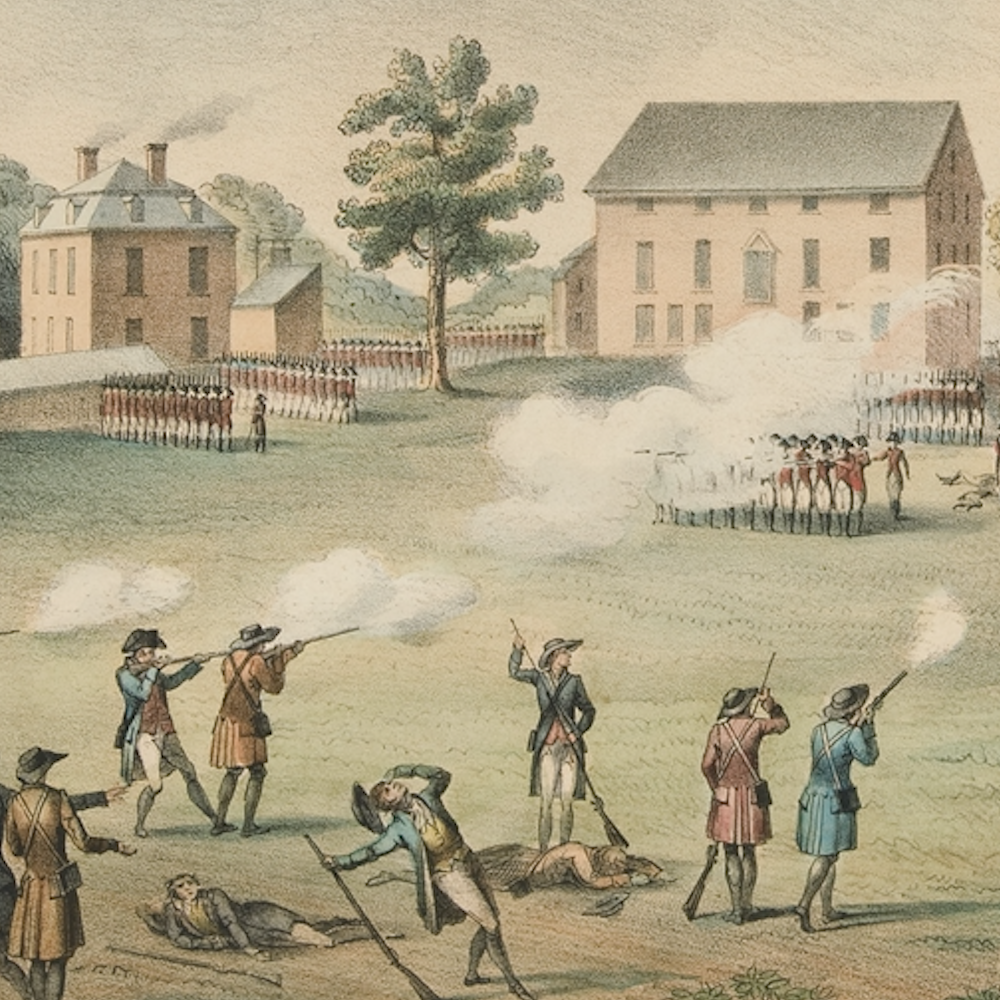

Imagining the Battle of Lexington

This lesson invites students to consider four different published images of the Battle of Lexington, created over 123 years beginning with one created in the summer of 1775. In the first image, Lexington militiamen are presented as victims, but in each of the succeeding images they are depicted returning British fire with increasing determination. The lesson asks students to consider why the depictions changed over time.

Imagining Lexington

Imagining the Battle of Bunker Hill

This lesson invites students to consider two contemporary images of the Battle of Bunker Hill, the first created in the summer of 1775 as a response to popular interest in the battle, and the second the familiar John Trumbull painting executed shortly after the war. The lessons asks students to compare the two and suggest why the artists chose to emphasize different aspects of the battle.

from our REVOLUTION ON PAPER lesson series:

Washington Takes Command

When George Washington attended the Second Continental Congress in 1775 as a Virginia delegate, he brought with him both the military reputation he had established during the French and Indian War as well as his militia uniform. As the Congress searched for a commander in chief of the army, some favored former British officer Charles Lee, but Samuel Adams argued the southern colonies would only support the cause if a Virginian led the army . . . and he promptly nominated George Washington.

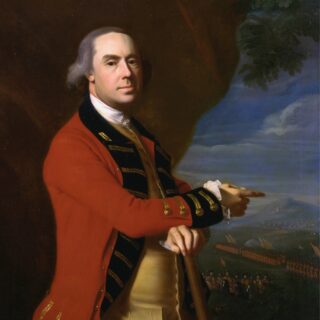

Between Commanders in Chief

The commander in chief of the Continental Army, George Washington, and the commander in chief of British forces in the New World, Thomas Gage, served together during the French and Indian War. They were among the few survivors of what became known as Braddock’s Defeat, a 1755 battle in the Ohio Valley where 977 of the 1,459 British and American soldiers were killed or wounded. Letters composed and exchanged between Washington and Gage in August 1775 shed light on their complicated relationship following the outbreak of hostilities in Massachusetts that propelled the United States and Great Britain into war.

George Washington’s Great Challenge

George Washington’s great challenge was to bring discipline, order and unity to an army comprised of volunteers divided by region, class and culture. His troops came from many parts of America, which at the time was like coming together from distant countries; different customs and manners sometimes caused misunderstandings and conflict. These volunteers joined the common cause but understood the meaning of that common cause in very different ways.

from our MASTER TEACHER-CREATED lesson collection:

WHERE DID THE LOYALISTS GO? ONE WOMAN’S JOURNEY

Students will use both primary and secondary sources to examine the legitimacy of Patriot and Loyalist claims during the American Revolution based on the experience of Georgia resident Elizabeth Lichtenstein Johnston.

One Woman's Journey