The president’s illness is not unprecedented. Indeed the presidency was less than two years old when the first president of the United States, George Washington, nearly died in one of the worst influenza epidemics of the eighteenth century.

A dangerous strain of influenza began spreading through the new nation in the fall of 1789. No one then understood the sources of epidemic disease. Noah Webster associated the epidemic with an eruption of Mount Vesuvius. “Such disorders in the elements,” he wrote, “never fail to produce epidemic diseases.” The eruption, he explained, was the herald “of the most severe period of sickness that has occurred in the United States in thirty years.”

Dr. Benjamin Rush, the leading physician in Philadelphia, told Webster that members of Congress had carried the epidemic from New York City, then the capital of the United States, to Philadelphia, where they had infected others. Webster didn’t believe it. “The opinion of its propagation by infection,” Webster wrote, “is very fallacious, as I know by repeated observations.” He thought the spread of the epidemic “depends almost entirely on the insensible qualities of the atmosphere.”

Whether or not the epidemic was caused by the rumblings of a volcano four thousand miles away or not, Webster tracked its spread. It soon “pervaded the wilderness and seized the Indians,” he wrote, and “overspread America, from the fifteenth to the forty-fifth degree of latitude in about six or eight weeks.” Webster detected a second wave of the epidemic beginning in March 1790. It was in Albany in early March, and central Connecticut about the middle of April. He thought it spread from there through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and moved on to the South.

New York City was particularly hard hit. In early May, Senator William Maclay reported that “the whole Town, or nearly so, is sick and many die daily.” Richard Henry Lee, another member of the Senate, described the city as “a perfect Hospital—few are well & many very sick.”

The president made no special effort to avoid the illness—the mechanics of disease transmission were not understood, so any precautions he took would probably have done no good. As a general proposition, Washington interacted relatively little with people outside his immediate household and was rarely in a crowd, where the risk of contracting an infection was greatest.

There was one exception. A year earlier—shortly after taking office—Washington had started the custom of holding weekly levees, at which any respectable person with business to discuss with the president could present himself at the president’s home, where they were conducted to a room set aside for this purpose. At the appointed time, a few minutes past three in the afternoon, Washington appeared and made his way around the room, conversing briefly with each person. The practice of setting aside a little time each week in this way was more efficient that indulging constant interruptions to meet with people, but in a city in the grips of an epidemic, these levees exposed the president to considerable risk of infection.

Washington apparently contracted influenza around the beginning of April. On April 6 Congressman Richard Bland Lee wrote that “the President has been unwell for a few days past.” Washington firmly believed that being tied to a desk was wrecking his health, and was sure that exercise was the best way to beat the illness. He set off on a riding tour of Long Island in the third week of April. Abigail Adams reported that Washington “has been very unwell through all the Spring, labouring with a villious disorder but thought, contrary to the advise of his Friends that he should excercise away without medical assistance; he made a Tour upon Long Island of eight or ten days which was a temporary relief.”

Despite his optimistic faith in exercise, Washington’s condition deteriorated. On May 7, Senator Maclay reported to Dr. Rush that the president had “nearly lost his hearing.” Members of Congress began to consider what might be done to deal with the president’s illness. Although the idea of the president temporarily transferring his powers to the vice president—now embodied in the Twenty-Fifth Amendment—had no legal foundation, congressmen suggested it. Abraham Baldwin of Georgia wrote that “Our great and good man has been unwell again this spring. I never saw him more emaciated . . . . If his health should not get confirmed soon, we must send him out to mount Vernon to farm a-while, and let the Vice manage here; his habits require so much exercise, and he is so fond of his plantation, that I have no doubt it would soon restore him. It is so important to us to keep him alive as long as he can live, that we must let him exercise as he pleases, if he will only live and let us know it. His name is always of vast importance, but any body can do the greater part of the work, that is to be done at present, he has got us well launched in the new ship.”

On Sunday, May 9, the president recorded in his diary that he was “Indisposed with a bad cold,” not imagining the ordeal ahead. He noted staying “home all day writing letters on private business. The president’s illness grew worse during the night, and the next day he was confined to bed, apparently suffering from a bad case of influenza that quickly led to pneumonia. Washington later described it as “a severe attack of the peripneumony kind.” James Madison, who had just recovered when the president was stricken, described Washington’s illness as “peripneumony, united probably with the Influenza.” Maryland congressman Michael Jenifer Stone described the illness as “Influenza Pleurisy and Peripneumony all at Once.”

Washington’s secretary, William Jackson, sent for Dr. Samuel Bard. one of the most prominent physicians in New York City. Bard had studied medicine in London and Edinburgh and returned to establish an extensive practice. He had stayed in the city through the British occupation during the war—a decision that led some to accuse him of loyalist views, but this did not hamper his practice. Bard had attended Washington the year before, when he operated (without anesthesia) to cut a tumor out of the president’s thigh.

At first Bard did not regard the president’s illness as life-threatening. On May 12, Martha Washington reported to Abigail Adams that “the President is a little better today than he was yesterday.” But as a precaution, Bard and Jackson sent a messenger to Philadelphia for Dr. John Jones, a highly regarded physician who had cared for Benjamin Franklin in his final illness. Benjamin Rush regarded Jones as the finest surgeon in the country. The message reached Jones at ten-thirty that morning. He was in New York by nightfall. Bard also called in two New York doctors, John Charlton and Charles McKnight, to consult on the president’s case. Charleton was an English surgeon who had come to New York as a surgeon in the British army and never left. McKnight had been a surgeon in Washington’s army.

We don’t know much about the treatments these doctors prescribed. Washington believed in the value of therapeutic bleeding to reduce fevers, and was bled repeatedly during his fatal illness in December 1799. But in the spring of 1790 his doctors seem to have relied on James’s Powder, a preparation introduced by an English physician, Richard James, in 1746. A patented combination of calcium pyrophosphate and antimony, its inventor claimed that the powder cured fevers and that it was also effective in reducing inflammation caused by gout. He said it even cured distemper in cattle. James’s Powder was prescribed for fevers into the twentieth century—a tremendous run for a quack remedy of no proven therapeutic value. Congressman Henry Wynkoop wisely suggested that Washington’s eventual recovery was “owing . . . more to the natural strength of his Constitution than the Aid of Medicine.”

The four physicians and those closest to Washington tried to keep details of the president’s illness from the public. “It was thought prudent,” Abigail Adams explained, “to say very little upon the Subject as a general allarm may have proved injurious to the present State of the government.”

The president’s illness grew worse on May 14 and 15, when his condition reached a crisis. Maclay—who was sick himself—went to the president’s house on the afternoon of May 15 and found the it crowded, and “every Eye full of Tears.” Dr. McKnight told Maclay that there was no longer reason for optimism, and that he “would Triffle neither with his own Character nor the public Expectation” by suggesting otherwise. McKnight warned that “danger was iminent, and every reason to expect, that the Event of his disorder would be unfortunate.” About five that evening, the physicians reported to Mrs. Washington and the president’s household that they expected the president to die.

The president, newspaper publisher John Fennon wrote, “expectorates blood & has a very high fever.” He was “Seazd with Hicups & rattling in the Throat,” said Abigail Adams, “so that Mrs Washington left his room thinking him dying.”

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson—ever the scientist—described what happened next in clinical terms. “In the evening a copious sweat came on, his expectoration, which had been thin and ichorous, began to assume a well digested form, his articulation became distinct, and in the course of two hours it was evident he had gone thro’ a favorable crisis.” On May 16, Jefferson wrote to his daughter that the president’s illness was abating. “He continues mending to-day, and from total despair we are now in good hopes of him.” Jefferson didn’t say why he thought Washington had survived the crisis, but Abigail Adams credited James’s Powder, which she said “produced a happy Effect by a profuse perspiration which reliefd his cough & Breathing.”

The household remained on edge but by the morning of May 17 improvement was clear. That evening, William Jackson wrote that “the President is much better, and, I trust, out of all danger.” By May 20 Washington was sufficiently recovered for Jackson to report to a Philadelphian that “the President’s recovery is now certain—the fever has entirely left him, and there is the best prospect of a perfect restoration of his health.” Richard Henry Lee was allowed into see Washington on May 22, and found the president sitting up in an easy chair. “The President is again on his legs,” Senator Philip Schuyler wrote on May 23. “He was yesterday able to traverse his room a dozen times.” James Madison recorded on May 25 that Washington was “so far advanced in his recovery” that he took a brief ride in his carriage.

As news of his recovery spread, expressions of relief were universal. American diplomat William Short wrote from Paris that reports of Washington’s “narrow escape affected sincerely all the friends to America here. His re-establishment gives great pleasure.” Martha Washington wrote appreciatively to Mercy Otis Warren about this outpouring of public concern: “During the President’s sickness, the kindness which everybody manifested, and the interest which was universally taken in his fate, were really very affecting to me. He seemed less concerned himself as to the event, than perhaps any other person in the United states. Happily he is now perfectly recovered, and I am restored to my ordinary state of tranquility, and usually good flow of spirits.”

The president’s illness left the fifty-eight-year-old Washington in what he called “a convalescent state for several weeks after the violence of it had passed,” with what he privately confessed was “little inclination to do more than what duty to the public required.” He wrote to Lafayette on June 3 that he had recovered “except in point of strength,” but in mid-June he was still experiencing chest pain, coughing, and shortness of breath. Washington’s doctors advised him to exercise more and devote less energy to public business. The president found this hard advice to follow, but as soon as he was able, he resumed exercising. He took a three-day fishing trip off Sandy Hook in June, and made plans for a trip to Rhode Island, which had recently ratified the Federal Constitution, becoming the thirteenth state.

George Washington knew that he was fortunate to have survived. Reflecting the common belief that each bout with disease used up the body’s ability to withstand future attacks, the president confided to his friend David Stuart that his next serious illness would “put me to sleep with my fathers.”

In our own time of troubles, the story of the first president’s illness offers this consolation: what seems so new to us is not so new. We have faced many dark nights when nothing but our ideals and our hope sustained us. We have a rich history of progress, ingenuity, determination, and experience. We have not simply endured. We have triumphed. We will again.

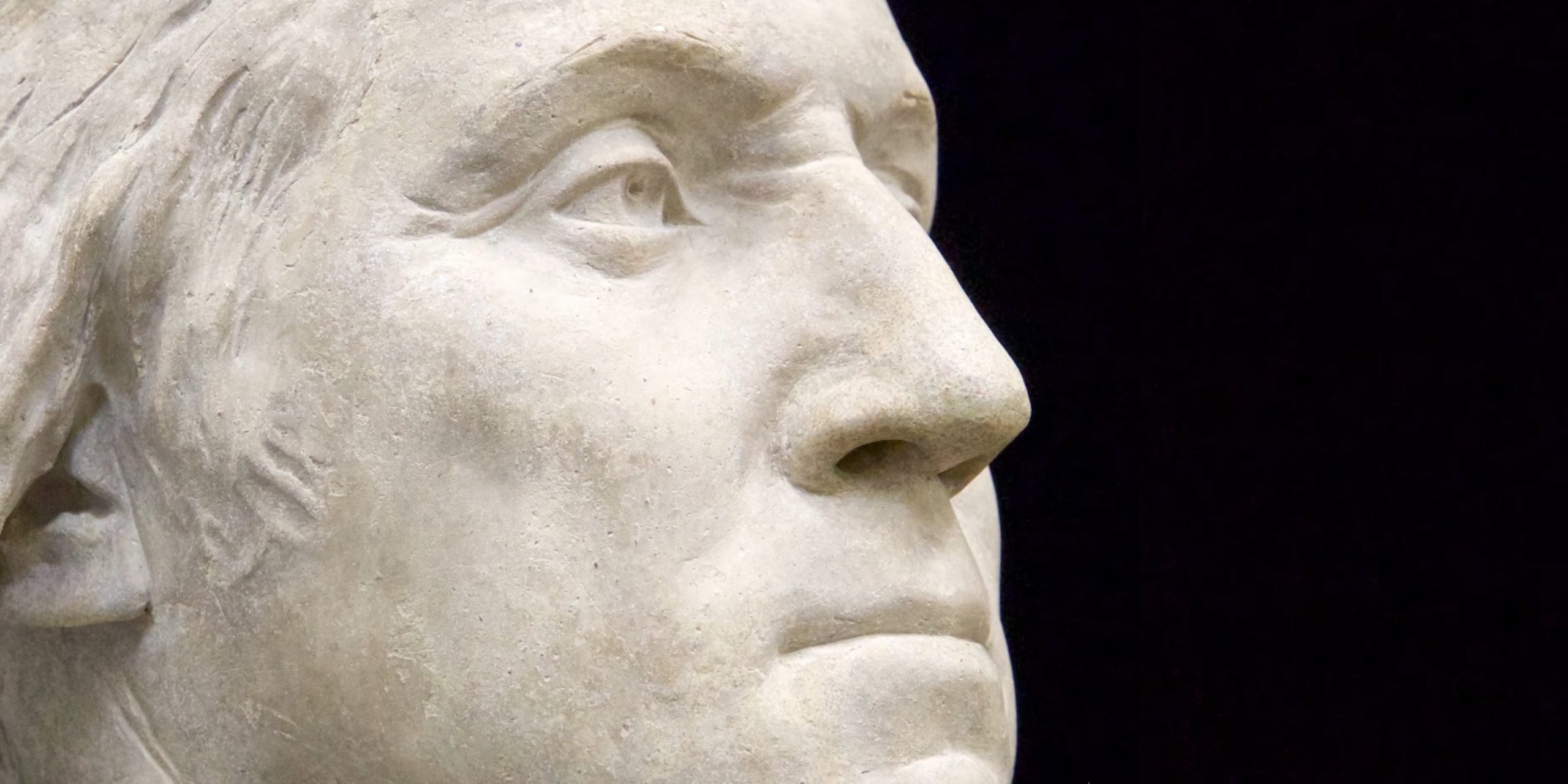

Above: Jean-Antoine Houdon sculpted this portrait bust of George Washington from life a few years before the general answered the call of his country to become the first president of the United States (Courtesy the Mount Vernon Ladies Association of the Union).

We encourage all our visitors to read Why the American Revolution Matters, our basic statement about the importance of the American Revolution. It outlines what every American should understand about the central event in American history. It will take you less than five minutes to read—and a few seconds to send the link to your friends, family, and colleagues so they can read it, too.

If you share our concern about ensuring that all Americans understand and appreciate the constructive achievements of the American Revolution, we invite you to join our movement. Sign up for news and notices from the American Revolution Institute. It costs nothing to express your commitment to thoughtful, responsible, balanced, non-partisan history education.

For more on epidemics in Revolutionary America, read Lessons from a Revolutionary Epidemic.